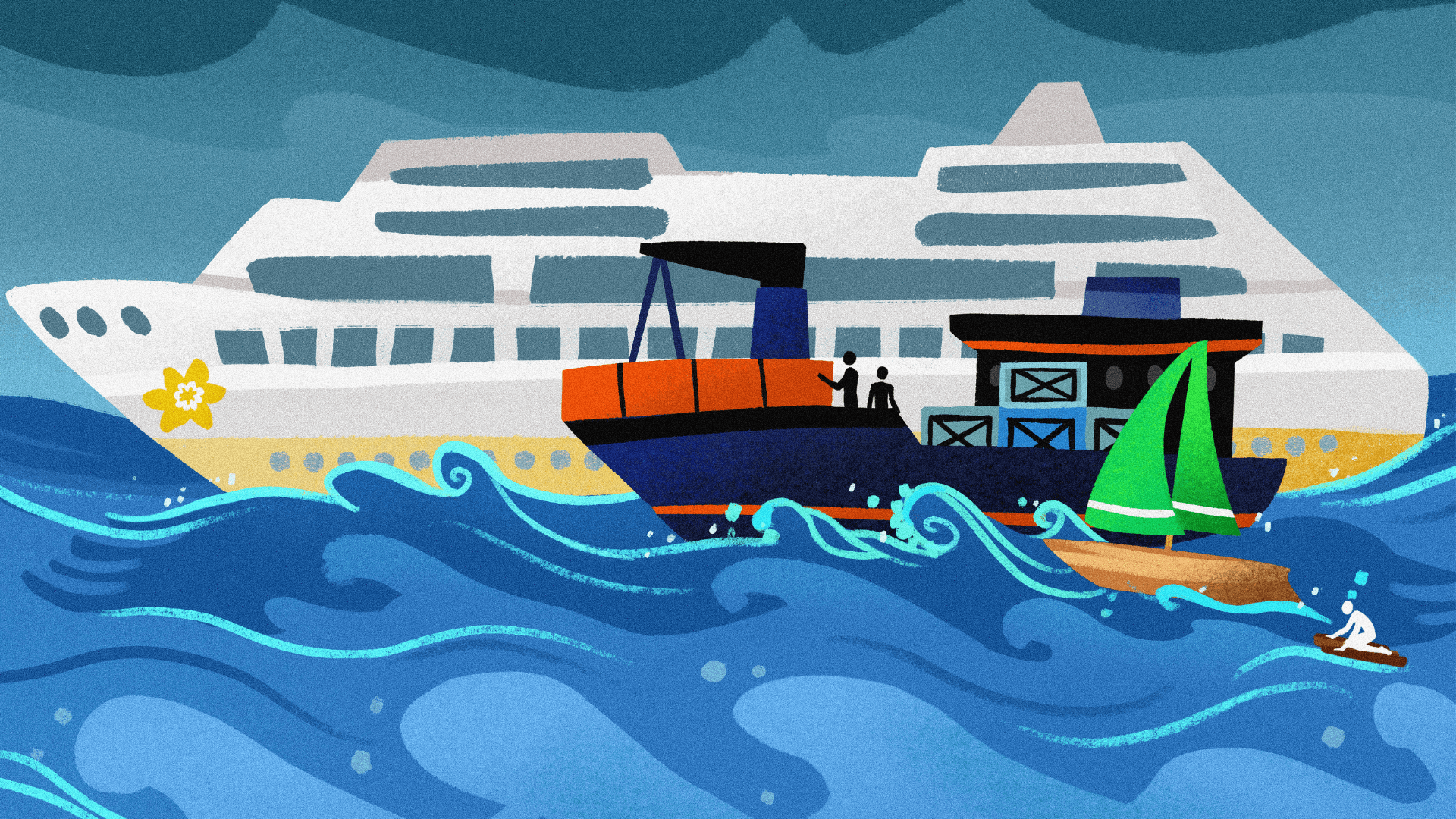

Same storm, different boats: A reflection on cancer, inequity and resilience

Subscribe to Catalyst

Subscribe to get our magazine delivered right to your inbox

Related Articles

Related Articles

Cancer.

It feels intensely personal when it happens to you. You think, “Why me?” Then, as you look at the statistics, you realize, “Why not me?”

Cancer is ubiquitous.

The day I received my cancer diagnosis, 675 other Canadians were hearing similar news. A stark reminder that I was part of a larger collective experience.

It’s happening to more and younger people. According to the Canadian Cancer Society, of those diagnosed with cancer in Canada, nearly 40 per cent are between the ages of 20 and 64. In other words, I’m in good company.

There are two sides to every coin, and while a cancer diagnosis is unlucky by any measure, the flip side is equally important.

I had comprehensive medical care, paid leave, a compass to navigate a complex system, and a network of supportive peers to buoy me up on my hardest days.

There’s a saying that we may all be in the same storm, but we’re not all in the same boat. That resonated deeply with me, once I was able to wrap my head around a new reality.

Not-so-normal

It all started in the fall of 2023. I was bone tired. No amount of rest would restore my energy levels. I couldn’t cook a meal or have a meeting without needing a nap. And I’d wake as tired as I was before.

Like a lot of men, stubbornness is among my hallmark traits. My spouse insisted I go to the doctor. Left to my own devices I may not have heeded the alarm my own body was raising. Being partnered with a strong and smart individual is another checkmark in my good fortune column.

But I’ll be honest. A diagnosis of prostate cancer felt like a slap in the face.

I was fairly young. Healthy. Fit. I ate right. It’s comforting to feel you have a modicum of control, and there are many things we can and should do to stay healthy. But it’s a kick in the teeth to realize those things aren’t always enough.

Try as you might, you can’t rationalize cancer away.

My cousin, and dear friend, died of prostate cancer at 59 – only months before my own disease came to light. He had to travel to Gatineau from Northern Quebec for treatment, another health disparity experienced by friends and neighbours in rural and remote communities.

Michel Rodrigue, President and CEO, Mental Health Commission of Canada.

A not-so-universal safety net

And while cancer doesn’t discriminate, socio-economic status does. Cancer is never a walk in the park. It’s a long, lonely night of the soul.

But my situation was offset by the ability to access psychological supports, medications, nutritious foods, and creature comforts.

Unlike 6.5 million people in Canada, I had a family doctor at the ready. Language wasn’t a barrier to understanding, and transportation and accommodation costs, when they were required, didn’t break the bank.

For many, the extreme of a cancer diagnosis is accompanied by a lifetime out-of-pocket costs – we’re talking about tens of thousands of dollars.

From where I sit, those of us who’ve walked this path and emerged, somewhat unscathed, have a responsibility to speak up.

Advocacy – for oneself or in the broader sense – is itself a privilege.

A healthy workplace: Antidote to illness

New research from the Canadian Cancer Society took the pulse of Canadians. Survey respondents were asked how they felt a cancer diagnosis might affect their finances. The responses were sobering:

- Nearly 30 per cent feared job loss

- Over 40 per cent anticipated career setbacks

- 80 per cent worried about long-term financial impacts

When you’re unwell, workplace support can be a lifeline. My experience was transformed by colleagues who did more than just accommodate – they actively supported my journey.

The stress and anxiety of my illness, an admittedly heavy burden, was lightened by colleagues sending supportive messages; shouldering the load while I was away; holding the space for me when I got back.

Flowers appeared on my desk. My team respected my treatment schedule; my uneven recovery; my uncertainty. When brain fog set in, they reminded me. When they saw I was flagging, they suggested we reconvene. When I wasn’t my best self, they gave me a pass.

But I couldn’t help reflecting on a critical inequity.

Cancer was met with visible support, while mental health challenges often remain shrouded in silence. We have a responsibility to fight back against the stigma that relegates a mental illness diagnosis as unworthy of the same empathy I received.

Peer-support: A priceless gift

Prostate cancer accounts for 20 per cent of new male cancer cases, but statistics don’t capture the human experience. The camaraderie with fellow patients, survivors and caregivers refilled my tank depleted by radiation.

That’s why I believe connection is our most powerful healing mechanism.

A naturally reserved person, I’ve worked to become more open as I age. Prostate cancer threatened this progress. It felt like a blight on my masculinity.

With others who had walked this path, I found a language of understanding that transcended medical terminology. We spoke about fears, and revealed vulnerabilities – both the mundane and monumental anxieties that accompany a cancer diagnosis.

To cope, or not to cope

Over the years, many of us have developed mechanisms to cope with life’s uncertainties – and the big “C” is a larger uncertainty than most.

But Cancer is stealthy. It undermines your confidence and robs you of the ability to concentrate and the energy to exercise.

My usual punishing bike rides through Gatineau Hills were out of the question. Over time, I grew to celebrate my smallest victories – a walk to the end of the driveway; taking the dog around the block.

A silver lining was rediscovering a love for music, forgotten in the hustle of daily life. When I felt like my feet were encased in cement, music let my spirit soar free.

Resilience isn’t about maintaining old capabilities. It’s about discovering new ones. But we’re not all given the same opportunity to do that.

From personal challenge to collective compassion

My experience threw into stark relief that privilege is the scaffolding on which resilience is built. I didn’t emerge from this journey transformed for the better because I did something remarkable to deserve it; I did so because I had the resources – financial and social – to be successful.

Resilience isn’t about returning to who you were, but about moving forward with newfound understanding. I’m committed to advocating for those who face greater challenges in their cancer experience.

Cancer shouldn’t be faced alone. It takes a society to mount the kind of powerful response we need.