Ainome is Using Data to Bridge Gaps

Subscribe to Catalyst

Subscribe to get our magazine delivered right to your inbox

Related Articles

Related Articles

Founder Taryn Ellens’ tech startup came together from a confluence of systems-level observations, lived experience, and persistent gaps that weren’t being addressed, especially in First Nations communities in the Yukon.

Ainome—pronounced like “I know me” is a mental wellness organization in Whitehorse that supports overlooked communities with “a sustained effort to reimagine how tech can reflect lived realities in underserved communities,” says Ellens, who is also a PhD neuroscience researcher at the University of Alberta.

In 2022, Ellens was working as a youth clinical counsellor when she realized that artificial intelligence tools could help identify gaps in her field and issues related to accessing care. The more she examined the data, the more she observed that traditional Western approaches to mental health were not working in many Indigenous communities.

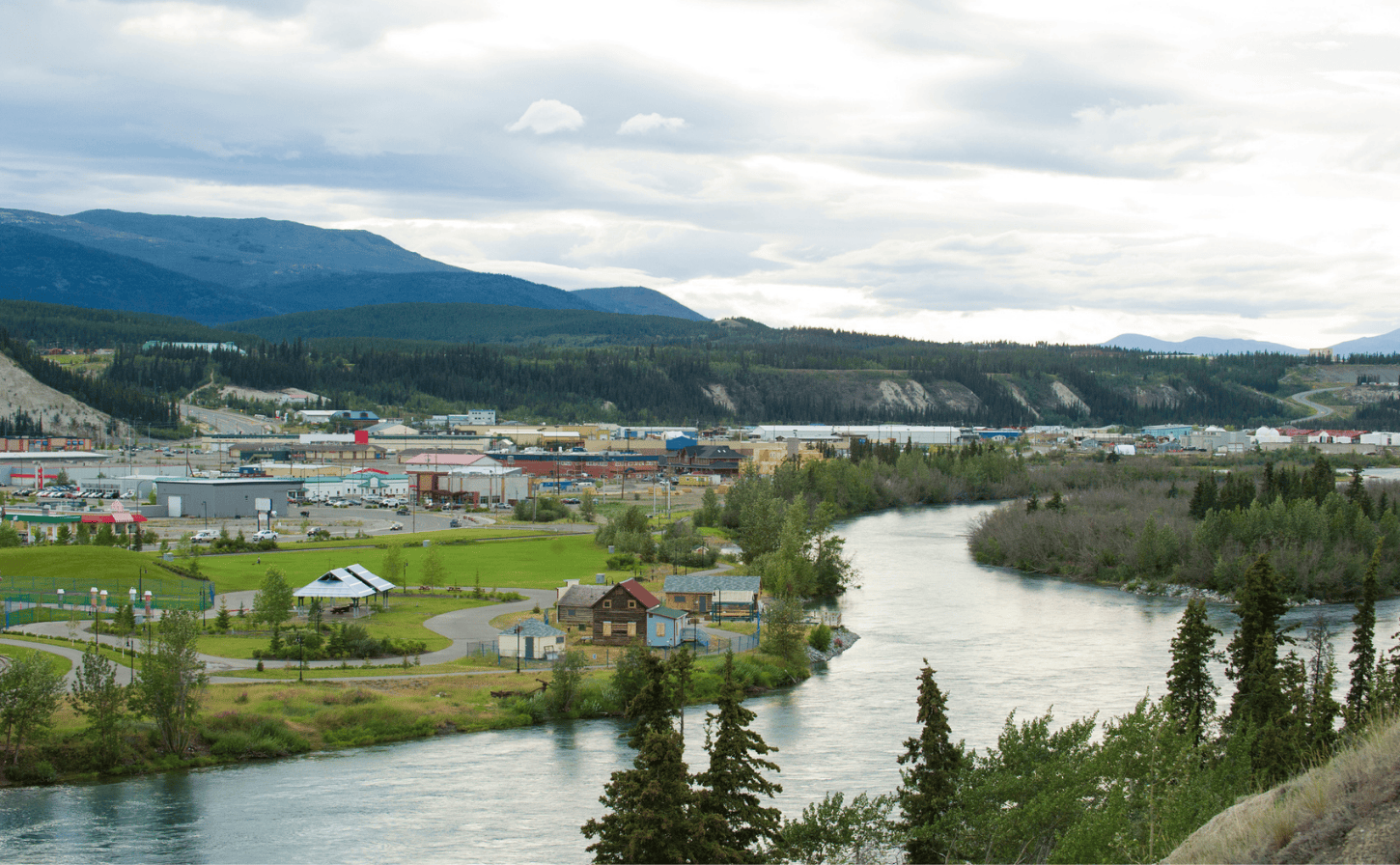

Whitehorse along the Yukon River. Photo: AscentXmedia.

Covering the distance

“In these isolated communities, the lack of access to health services is compounded by the emotional toll of their geographic isolation,” Ellens wrote in late 2024 in the Yukon News. “Most of these areas are located far from urban centres, where mental health care is typically concentrated. The burden of travel, both financial and emotional, prevents many people from accessing the care they need.”

Geography is one part of the issue. “Historical trauma continues to have a profound impact on First Nations’ mental health. Colonial practices, such as residential schools and the forced suppression of Indigenous cultures, have directly caused intergenerational trauma. This trauma, combined with systemic discrimination and forced disconnection from traditional lands, has created a mental health crisis that mainstream services have often failed to address adequately.”

Tech support

Yukon dedicated the largest share of its federal bilateral health funding to mental health, according to a 2024 Canadian Mental Health Association report. The investment is designed to complement wellness and substance use strategies to address high rates of self-harm and deaths. Ellens says these investments help to boost what’s happening locally.

After three years of examining mental health access gaps for First Nations people, Ellens began to design a mental health index – a collection of data that includes numerous social determinants of health (the non-medical influences on our health) and their links to accessing mental health supports. For example, housing is considered a social determinant of health. If you have stable housing, you are in a better position to care for your mental health and access services than if you lack shelter.

The index is nestled into a larger vision—one of a dynamic, community-owned tool designed to surface what mainstream systems might miss regarding non-medical indicators, along with indicators of wellness and cultural practices, such as access to Elders and availability of ceremonial activities. It’s less about scoring or grading and more about making invisible patterns visible to support a self-determined strategy.

Ellens and her team develop models that interpret layered, anonymized data sets drawn from online mental wellness tools. By detecting subtle patterns, such as indicators of distress or early shifts in wellness, the models help decision-makers anticipate mental health trends, even in contexts where formal diagnostic data is limited. The goal is to support proactive responses, including culturally grounded approaches such as land-based healing, traditional storytelling, and community gatherings. All data remains fully anonymized and under the governance of First Nations communities.

In widening the lens on what defines wellness, Ellens wants to invite Indigenous knowledge systems into the mental health field. Part of that means confronting the shortcomings of traditional talk therapy and harnessing technology to support positive outcomes and approaches to care – something clients have been asking for.

“Instead of a deficit-based model, focused on what is wrong, technology can be used to look back at what factors were in place in order to move toward a rehabilitation narrative,” she says.

“Even a basic term like ‘trauma recovery’ implies that when you have ‘recovered’ you are no longer affected by the trauma, but that’s not true,” she says, noting that the act of talking it out can be re-traumatizing for some, but it may work for others, depending on the context. “Sometimes it’s more about talking about successes and mapping out how resilience happens to gain insights,” she says. To account for this approach, Ainome’s tools ask questions to develop additional options for existing therapeutic modalities.

Taryn Ellens founded Ainome – pronounced “I know me” to support self-determined strategies for mental health and wellness in Indigenous communities. Photo: Manu Keggenhoff.

New approaches to therapy

A shift in approach is one way of adopting and adapting mental health in Indigenous communities; another is improving access through online resources, which can make a difference between having and not having care, particularly in geographically remote communities. Virtual counselling was very appealing to Colbi Mike; it was the first place she looked when searching for a new therapist.

Mike was looking for a way to bridge cultural teachings from her Indigenous background with standard mental health approaches. The 27-year-old is from Poundmaker Cree Nation in Saskatchewan and is the first generation in her family to grow up outside of the residential school system. Mike sits on the Youth Council of the Mental Health Commission of Canada, offering insights on addressing barriers to maternal mental health and the effects of oppression on Indigenous peoples.

“I grew up with different teachings – go to Elders, do ceremony, be with family,” Mike says. “So, when I first started seeing a therapist when I was very young, it felt like an internal struggle, like I was betraying someone,” she says. She started to move from in-person to online therapy to find an approach that would meet her needs. She says it took a bit of work to ensure the services would be covered under her health plan, and the get-to-know-you sessions felt a bit slow. However, once things ramped up, Mike felt that she hit a stride with her current practitioner.

“We had a lot to say to each other,” she says. “I’m an info-intake person, and my therapist is willing to share her personal experience in connection with mine, as she has children too.”

Online therapy offers other opportunities, Mike notes. “Being in the comfort of my own home, I’m able to smudge,” she says. “Having a space that I’m able to cleanse myself, before and after therapy, has been really important to me.”

As practitioners and organizations seek to improve access to mental health, considerations are being made for data sovereignty, online safety, and culturally appropriate care, while also considering what innovations are possible, such as through the work of Ainome and other startups, that make space for culture and connection.

It’s a chance to imagine better, Ellens says. “Ainome was born from frustration with existing systems that weren’t telling the full story around mental wellness and Indigenous self-determination, and with the hope that we could use technology in ways that heal rather than harm. Our work is about co-creating tools that reflect lived experience and community-led definitions of care.”

Taryn Ellens will present at the Electronic Mental Health Collaborative’s (eMHIC) 10th annual congress in Toronto, November 19-21. This year’s theme is Global Mental Health Equity: Digital Solutions for an Interconnected World. Find the full list of speakers here.

Dayanti Karunaratne runs the family farm in rural Hawaii and takes a keen interest in food sovereignty when not researching and writing on topics of human interest.