The Living Legacy of a Stillborn Child

Subscribe to Catalyst

Subscribe to get our magazine delivered right to your inbox

Related Articles

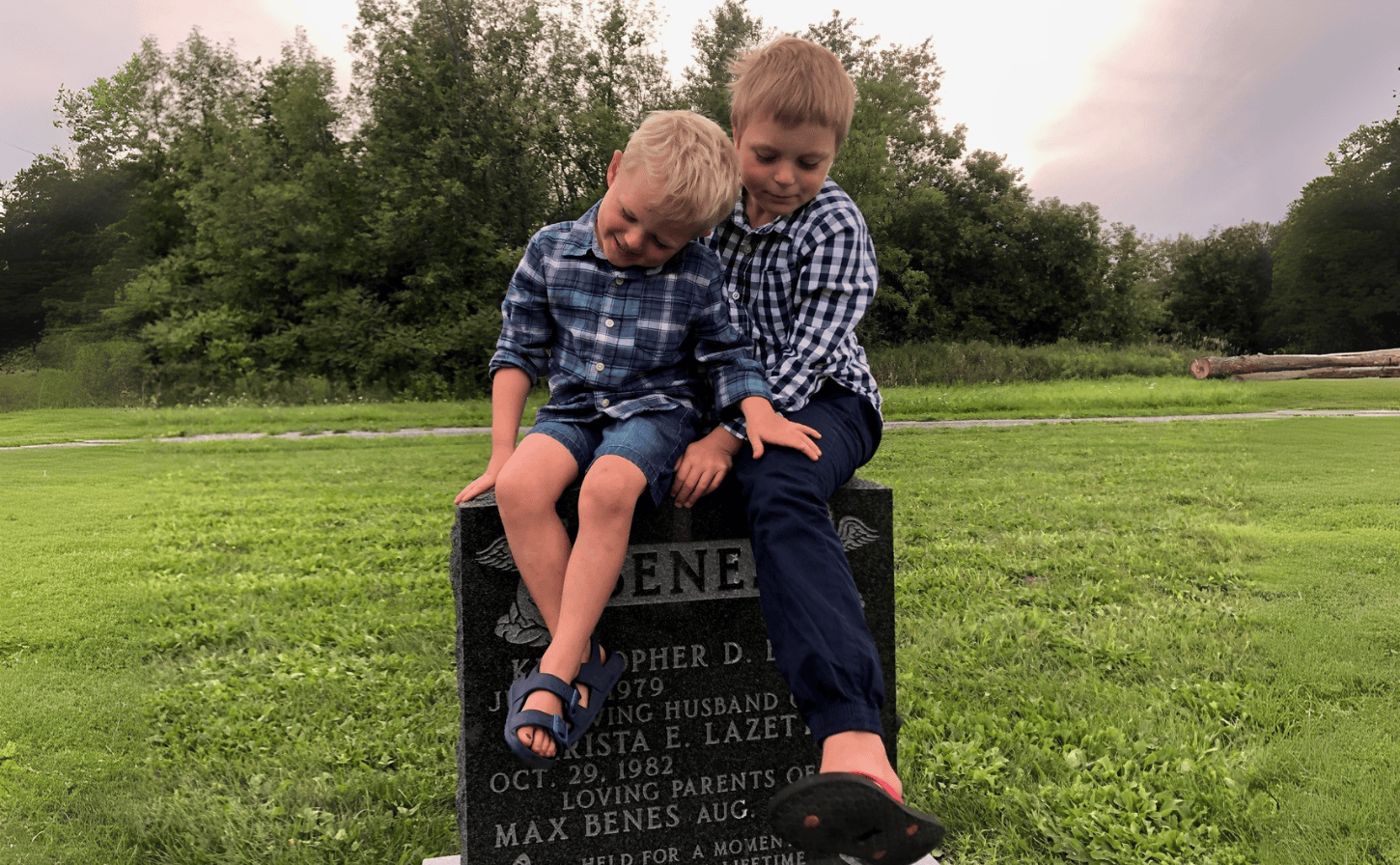

There were so many people waiting to meet Max, but only his father and I got to see and hold him. For his older brother Henry, our extended family and friends, and especially for his younger brother, Simon—who came later—it could easily feel like Max didn’t exist. But he did exist. Max was born on August 30, 2014.

Eleven years ago, Krista Beneš was a working mom with a healthy two-year-old and a busy life. Her second pregnancy was progressing exactly as expected until Krista noticed a decrease in the baby’s movement.

My OBGYN did a quick scan. We saw the baby moving, and I felt reassured. Later that week, though, something continued to bother me. I remember driving to the Ottawa Civic Hospital to have it checked out. My husband, Kris, offered to come, but he was working, and I’d already started maternity leave. I said I’d call him after we got the all-clear.

When an ultrasound didn’t detect the baby’s heartbeat, I went into shock. I couldn’t fathom how the outcome we’d imagined—this vision of our healthy baby and the life we’d have together—could be taken away so abruptly. Kris rushed to my side. The induction commenced, and I laboured, listening to other babies being born, knowing I would never hear Max’s cries. The delivery process took two days.

We’d spent weeks preparing Max’s room, painting a navy-and-white accent wall, arranging all the cozy touches. Everything was set to welcome him home. Instead, Max was born still at 38 weeks.

Kris and I held him for what felt like only a few fleeting moments. Our hospital room was marked with a butterfly to signify what had happened. A volunteer photographer came, which struck me at the time as a terrible idea—why would somebody want to take photos of my dead baby? But now, I cherish those remembrance portraits. Max was loved. He still is.

Big brothers Simon and Henry pay tribute to Max.

You move so quickly, from expecting to celebrate a brand-new baby to planning their funeral. Kris and I had never even thought about where we were going to be buried. Now, we had to decide for Max. The situation tested our spiritual beliefs in an impossibly immediate way. All I knew for sure was that I couldn’t leave my baby all alone.

We found a place with Max’s great-grandparents, not far from where I grew up. It is a familiar space, close enough to home. With the support of family and friends, we got through it. There were weeks and weeks of meal drop-offs, flower deliveries, house-cleaning services, good thoughts, and warm wishes.

A network of support

My first priorities were healing my body and caring for Henry. When he was in daycare, I cried and slept. When he was home, I rallied myself to play with him, so his mommy wasn’t completely overtaken by the dark cloud of sorrow.

After about six weeks, a grief group opened up through Roger Neilson House (now called Roger Neilson Children’s Hospice). Kris and I signed up together. That’s where we learned it was okay to share Max’s photos, okay to talk about him. It was important to understand that we could include Max as part of our family and bring his memory into our day-to-day.

Carol Openshaw, who co-facilitated the bereaved parents’ group, noticed that families whose children had died in infancy sometimes didn’t return after the first session. She suspected those parents—who never got to know their child—found it hard to relate to parents who’d had years to watch their children grow. Disenfranchised grief is incredibly isolating, so Carol initiated a peer-support program to help match people whose experiences mirrored one another. That’s how I met Julia Winslow. Her son, Carter, was born still at 38 weeks, just like Max.

You can’t imagine the difference it makes to have someone you can text: I just walked past the diaper aisle and now I’m crying, and they get exactly how you feel. Even now, Julia continues to be an important touchstone in my life.

When Julia left the hospital after Carter’s stillbirth, she got a pamphlet on suicide prevention. That’s it. The leaflet validated the emotional severity of losing a child, but it didn’t come close to meeting her needs. Over the past decade, Julia has helped narrow that resource gap by taking on a leadership role with the Butterfly Run, which supports Ottawa families who’ve experienced loss during pregnancy and infertility. They’ve helped thousands of people, and the run has spread to communities like Vancouver, Kelowna, Nanaimo and Whistler.

Thanks to these and other ongoing efforts, a wide range of resources has been developed to support families across Canada. The stigma of losing a child used to mean people hid themselves away. Now, people are finding one another in ways that are healing and affirming.

Krista Beneš recently made a career change as Manager of Prenatal Screening and Complex Perinatal Portfolio at the Better Outcomes Registry & Network (BORN).

Cherished memories

When I became pregnant again, with our son Simon, anxieties naturally arose. Along with physical concerns, there were also nagging worries like, ‘What if everyone forgets about Max?’

Henry helped alleviate that fear when he first took part in his school’s annual Terry Fox Run. Each student was given the chance to dedicate their run to someone, and Henry’s tribute card read, “Terry ran for me, I am running for Max.” I was so proud. Henry’s tribute made me think we must be doing something right, teaching our boys that they can remember their brother.

Other people remember Max, too. Loved ones still call or text me on his birthday. It means a lot. I’m not suggesting that everyone needs to do this, but the shared acknowledgement feels supportive to me.

With each passing year, our love for Max grows more layered, and his mattering in our family never wavers. Earlier this year, I saw a job posting that asked, “Are you passionate about improving the health outcomes for pregnant individuals and their babies?”

I felt this pull. I’d been at the Mental Health Commission of Canada for nine years and loved it, but who better to contribute to an understanding of how we could do this than someone who’s experienced the most devastating outcome of all?

Now, after taking a big professional leap, I’m surrounded by a team of incredibly bright, passionate individuals who are all working towards the vision of ensuring the best possible beginnings for lifelong health. What a great way to honour Max’s legacy.

As told to Jessica Waite, a best-selling author and award-winning essayist who writes frequently about grief – and hope.

Resources:

- At the Pregnancy and Infant Loss Support Centre, the practitioner team consists of bereaved parents whose direct experiences have led them into counselling and coaching work.

- Aditi Lovering, founder of PILSC, says their intention is to meet people where they are: no matter how long it’s been since the loss, no matter how far along the pregnancy was, no matter if the bereaved person isn’t the parent who conceived the child. PILSC offers peer support, professional support, comfort boxes, and online resources.

- Lesley Sabourin says Roger Neilson Children’s Hospice also recognizes that grandparents, siblings, and extended family members can benefit from grief support. They’ve expanded their services to meet those needs and refer many Ontarians to the Pregnancy and Infant Loss Network.

- For bereaved parents still trying to build their families, Roger Neilson Children’s Hospice offers a program called Pregnancy After Loss Support and recommends org for people without direct access to the program.

- The hospice also lists other resources on its website.

- Krista recommends the book We Were Gonna Have a Baby, but We Had an Angel Instead for young children who have lost a sibling.

- Where to Find Mental Health Care in Canada: The Commission compiled a guide to obtaining private and public mental health services.