Supporting those close to us during a pandemic

Subscribe to Catalyst

Subscribe to get our magazine delivered right to your inbox

Related Articles

Subscribe to Catalyst

Subscribe to get our magazine delivered right to your inbox

Related Articles

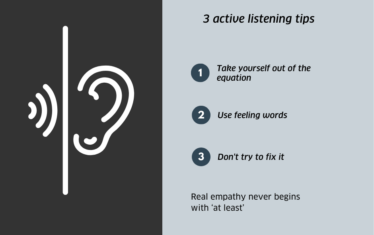

How real empathy never begins with ‘at least’

This winter, many of us are going to be called on to support friends and family at a distance.

But according to Kids Help Phone volunteer Cleo Edgington, who is also a program coordinator for Prevention and Promotion Initiatives at the Mental Health Commission of Canada (MHCC), “knowing how to do that well takes practice.”

While empathy may be natural to some of us, that doesn’t mean we know how to effectively convey it — especially over the phone or through a text message.

“Put it like this,” said Julia Armstrong, who is also a Kids Help Phone volunteer (plus a former counsellor) and the acting manager for Mental Health and Substance Use at the MHCC, “empathy never begins with ‘at least.’”

What Armstrong is getting at is the unconscious habit many of us have of trying to find a silver lining. “We don’t realize how unhelpful it is to say, ‘At least you have your health’ or ‘At least you have a home’ to someone who’s in a dark place. Doing that not only diminishes their feelings, it also layers them with guilt.”

Active listening: What it actually means

In a sit-down video chat with three MHCC staff members who moonlight as text or phone supporters, it became clear that active listening is a skill we all need to develop, and even if we think we’ve done so there’s no shame in needing a primer.

“It’s actually counterintuitive,” said Edgington. “Because you want to help people, you think, ‘How can I fix this?’ but that’s not your job. Your role as someone with a listening ear is to meet them where they are, validate their feelings, and be present as they tell you what they are or aren’t ready to do.”

Armstrong agreed. “We can’t assume responsibility for the problems others are having. That robs them of the confidence that comes with finding their own solutions. Besides, solutions are unique to each person. It takes humility to understand that you can walk alongside someone on their journey without leading the way.”

The right way to share

There are, it turns out, specific ways to meaningfully support the people in our lives. And one of the most important, which the three supporters echoed throughout our conversation, is to take yourself out of the equation.

“It can be so tempting to say, ‘I’ve been there,’ or, ‘I know how you feel,’ or even something specific like, ‘When I lost my pet…’, said Armstrong. This intention to connect and reaffirm the shared human experience is good. But by turning the spotlight on ourselves, we’re inadvertently diminishing the pain being disclosed to us in that moment. So instead, if you keep that intention but alter the approach, the impact you’ll have will be completely different.”

To illustrate, Edgington gave a couple of examples: “Just say, ‘That must be so hard’ or, ‘I can see why that’s devastating.”

And be specific, added Armstrong. “Use feeling words, so the person you’re talking to can correct or redirect you if you’re wrong. If you say something like, ‘It’s understandable to feel depressed,”’ the person might text back, ‘I’m not sad, I’m pissed!,’ which tells you that you need to recalibrate the conversation.”

Getting out of the way

The goal with active listening, whether you’re on the phone with your grandma or texting with your nephew, is to hold up a mirror so they can see their situation more clearly.

“As the listener,” said Edgington, “there’s a second reason for not reflecting your own experience back to them: doing so implies that you’ve got the same resources, the same tools, the same trajectory. And that may not be the case.”

Armstrong and Edgington also caution us against the harms of toxic positivity. “Telling someone it’s going to be OK isn’t a panacea. In fact, it can do more harm than good. We might have lived through something, and we might want to reassure them that they’ll overcome this dark time, but it’s not inherently helpful. Sometimes, it can make them feel worse,” Edgington explained.

The gift of listening

For Ryan Murphy, the MHCC program manager for Prevention and Promotion Initiatives, who also volunteers with Ottawa Victim Services and Kids Help Phone, the satisfaction that comes from supporting others goes beyond listening well.

“Yes, you’re validating feelings. Yes, you’re creating a safe space free from judgment. But you’re reminding people of their own problem-solving skills. You’re reaffirming their resourcefulness and, maybe above all, you’re letting them see their own worth. That doesn’t feel like a passive activity.”

This was certainly the case when, during one of his volunteer shifts, he found himself texting with a girl on her 10th birthday.

Clearly emotional, Murphy recalled the text coming in like it was yesterday. “She messaged and said her birthday had gone completely unnoticed. She felt she didn’t have any friends, and her family gave her no acknowledgment whatsoever.”

So, he said, they “celebrated” together. And what comprised that celebration was Murphy reaffirming to a lost and lonely child that she was deserving. “I was able to tell her, I hear you, I’m with you, and you are a worthy human being.”

Armstrong, tearing up herself, said to Murphy, “Think about that for a second. Think about what a gift you were able to give her. And think about how lucky she was that her text landed in your lap. For all the negative, she is going to look back on that day and know that someone — someone as special and empathetic as you — cared.”

Enter COVID

While all three affirm that volunteering in this way is deeply meaningful, they also admit that the pandemic is diminishing everyone’s capacity for giving — including those we rely on to pick up the phone or answer the texts.

“I feel incredibly energized after these interactions,” Murphy said, “but I don’t have the stamina to do as many sessions as I did before COVID-19.”

Armstrong understands that feeling. “Even as someone who derives tremendous satisfaction from this work, you have to know your limits, and you have to give yourself permission to set boundaries.”

That advice spills over into personal life as well.

“When acting as supports for others, we can’t neglect our own health and wellness, and it’s important to not only listen to others, but also to ourselves,” said Murphy.

For more information on how to get involved in supporting those in need, visit Kids Help Phone and Ottawa Victim Services.

Suzanne Westover

An Ottawa writer and former speechwriter, and Manager of Communications at the Mental Health Commission of Canada. A homebody who always has her nose in a book, she bakes a mean lemon loaf (some would call her a one-dish wonder) and enjoys watching movies with her husband and 13-year-old daughter. Suzanne’s time with the MHCC cemented her interest in mental health, and she remains a life-long learner on the subject.