Designing for Equity

Subscribe to Catalyst

Subscribe to get our magazine delivered right to your inbox

Related Articles

Related Articles

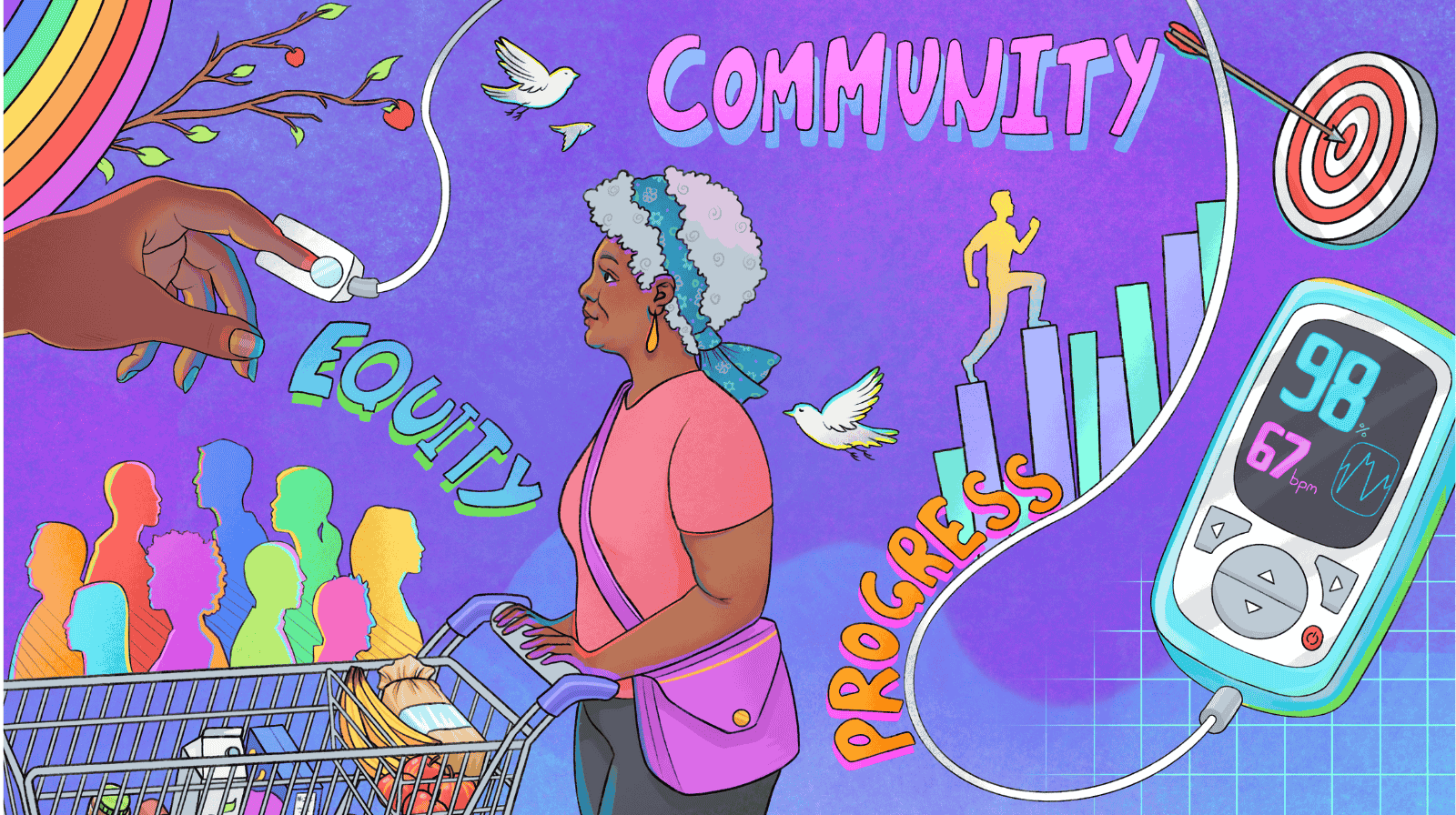

Black History Month 2025 is focused on Black legacy, leadership, and uplifting future generations, a topic we’ve explored in The Catalyst through stories on rallying or searching for culturally appropriate care. In this piece, we ask how more equitable futures can be made possible through design for African, Caribbean, and Black communities, and others not represented by the “average.”

I was grocery shopping when a clerk approached and started processing my cart at the self-checkout. It was quiet. I didn’t ask for help, and she didn’t ask if I needed any. She just stood next to me and started putting my items through.

Some people might say that this is good service, but it didn’t feel that way. It felt like she thought I was too stupid or slow to understand how to scan my items. She didn’t approach other shoppers; a young man at one checkout and a mother with a small child at another. So, based on my past experiences, I wondered if she thought I would try to steal the groceries.

I am Black, and I’ve been followed through stores on more than one occasion. Yet my items were neither subtle nor expensive: paper towels, a bag of rice, and a few other items –hardly the slip-it-into-your-pocket selection. It also wasn’t busy enough for me to go unobserved, so what was the deal?

Then, another thought occurred to me as I was leaving, and she made her way over to “help” another client who had not asked. What we had in common was grey hair.

Bias is two steps forward, one step back

I wanted to sigh and dismiss it, but the more I thought about it, the more aggravated I felt. How many biases against you are too many?

I’m comfortable in my skin, doing what I love and doing it well, so why did that clerk bug me? Because her actions belittled me; they made me feel less. It upset me and I’m not alone.

According to an American Association of Retired Persons study, almost two out of three women age 50 and older in the U.S. report they are regularly discriminated against and those experiences impact their mental health.

Women – particularly women of colour – carry the burden of intersectional prejudices of age, ethnicity, gender, and socio-economic status, among others.

If you’re thinking, yes, but that’s the U.S., then know that in Canada, we face a similar picture. A 2024 Women of Influence survey found that eighty percent of women say they experienced ageism in the workplace. An equal number witnessed women in their workplace being discriminated against based on age.

How do they know? It shows up as being ignored when providing advice and then having the same advice applauded when it’s delivered by a younger or male colleague. It’s the snide comments, being passed over for promotion, or any number of things that make them feel unheard, unseen, or incapable.

Average Has Never Worked

Presumably, most people don’t think ageism, sexism, or racism are attributes to aim for, but beyond the morality considerations, the health costs, and the societal impacts, there are bottom-line business costs that come with these biases.

Sharon Nyangweso, founder and CEO of QuakeLab, a niche agency that applies an equity lens to solve corporate and social challenges, puts it best when she says that we need to see equity as a technical skill.

“Long gone are the days of effective business leaders seeing equity as a ‘nice to have’ or social thing done for a few employees,” she says. “Equity is about building better products, services, and processes. It’s about not injuring or killing people because we can’t see beyond the needs of the ‘average person.’”

Take, for example, pulse oximeters. These small sensors are clipped to a finger or toe and use light to measure oxygen saturation in the blood. They are everywhere. According to Fortune Business Insights, the market was valued at $2.24 billion in 2023 and is expected to grow to $3.56 billion by 2032.

It’s been known for decades that everything from skin pigmentation and melanin to nail polish affects a pulse oximeter’s ability to accurately measure oxygen saturation. For Asian, Black, and Hispanic patients, this can lead to inaccurate readings. Further, those inaccuracies may also be associated with disparities in care, according to the Journal of the American Medical Association.

“Would you call that device effective?” Nyangweso asks. “Would you say that someone who engineered a product that didn’t work for its intended audience was a good engineer? When equity is integrated as a skill set, it considers all people in the design process, and that produces better, truly universal products, processes, and services.”

Say what?

Our stores are filled with products that unintentionally fail to serve their intended audiences. If you’ve ever failed to get a response from an AI-assisted audio device because you have an accent, you quickly understand what it means to use a device created for “the average” user.

What happens when we use AI devices to make decisions that impact people? So far, we know that it can wrongfully send more Black people to prison, inaccurately predict healthcare needs of Black patients, produce sexualized images of Asian women, program ageism into job application processes, and the list goes on. AI isn’t awful, it’s just built with our societal biases.

It’s not just AI. We have smartphones, cars, fitness trackers, and knee prostheses built for men – although women and other genders are also users. Given that women are the primary decision makers for consumer purchases, representing 70–80 percent of all consumer spending and representing about half of the population, how is that effective design?

This is what comes from building for the “average,” which is code for white males. It’s an approach that results in ineffective products, processes, and services that show a bias against their target market.

Even more amazing, products built for the average white man don’t properly meet most of their needs either. Flip through The End of Average by Todd Rose to learn more about that.

Equity as a Required Skillset

When you operate in an environment that doesn’t fit you, or support you, and indeed seems engineered to harm you, it takes a toll. That’s in part why there is often an emotional layer that comes with discussions of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI).

Nyangweso described the intersection this way, “People have conflated the work that we do in this field with morality or moralization and that mixes things up and distracts us from talking about the problem we are trying to solve. Instead of addressing the issue the way you would any workplace challenge, people expect me – someone who works in this field – to be their assessors or the morality police,” she says.

“We need to force the question of equity to be a question of professional obligation and responsibility. I want to walk into the room as a professional. I’m not there to talk about everyone’s feelings. I’m not there to beat back decades of socialization.”

Not only is that an impossible task, but it distracts from the real work of DEI by placing an emotional burden on the people trying to fix real problems that create tangible threats to patients, consumers, and clients.

“To understand equity as a technical skill, and to do the work of the field, you have to appreciate the three segments or aspects of DEI work,” Nyangweso says, listing them as:

- Equity as an intellectual activity or academic process.

- Activism.

- Professionalized equity.

Equity as an intellectual activity or academic process means research and data. For example, saying ageism is an issue can’t happen until someone does the work of measuring perceptions and impacts.

Activism, as Nyangweso describes it, is “that practical process where we are trying to reach liberation in the world.”

This work calls into question the status quo, forces us to have conversations about things we took for granted, and eventually leads people to question the way we do things and why we do them. It is the emotional lift that starts the ball of change rolling. How many conversations were prompted by Black Lives Matters or Every Child Matters?

Professionalized equity falls within change management tactics and is often how organizations implement the change processes required to become more equitable producers, suppliers, and employers.

Nyangweso notes that there are multiple intersection points with the three. “The work of activists supports the DEI sector, and makes professionalized equity work possible, and research is used to inform practices and approaches.”

All three segments are valid and serve different purposes. When we default to one without consideration for the others, then real change is not just hampered, it can become impossible. Similarly, when we try to use the tactics for one, to implement another, we will be disappointed by the results. For instance, using the tools of activism to develop tactics for professionalized equity will leave us frustrated by the constraints of a corporate environment and the speed of change.

Equity works

All workplaces do better when psychological safety, a byproduct of equitable spaces, is present. Psychological safety is about feeling free to be who you are at work. It’s about being able to engage without fear of punishment or other negative consequences. For employers, it not only improves the workplace environment, but psychological safety also means financial advantage through increased productivity and lower absenteeism and turnover.

We all live with the challenge of managing within an inequitable world. We can perpetuate those inequities by pretending they don’t exist, don’t impact us, or those around us – or we can take the initiative and make changes where we’re at. We can question why we ignore the advice of older employees; we can call it when we hear inappropriate comments about people based on age, gender, race, sexual orientation, or anything else that doesn’t reflect respectful engagement.

The absence of equitable thinking in the development of work has real world consequences. To do your job effectively, whether you’re a grocery store clerk or a product developer, you need to learn, understand and live diversity, equity, and inclusion.

Further reading: Rallying While Black.

Resource: Psychological Health and Safety Training and Assessment.

Author: Debra Yearwood looks for silver linings – and not just in her hair – she is the Director of Marketing & Communications at the Mental Health Commission of Canada.

Illustration by Holly Craib