Subscribe to Catalyst

Subscribe to get our magazine delivered right to your inbox

Related Articles

Related Articles

This is a story for any day of the year – but we want to note the 2024 theme for International Overdose Awareness Day – held annually on August 31 – which is “Together We Can.” The topic highlights the power of communities standing together to end overdose.

I have a kit that reverses opioid overdose, and I am not ashamed.

It is not only those members of the population who live with substance use concerns who could owe their lives to naloxone; it is also people who live with chronic pain and take prescription pain medications – like my wife. Or people like my son who could get into that pain medication by accident. It is all of us who, in our daily lives, could come across other people who – for whatever reason – have overdosed on opioids.

This can happen anywhere – including in the workplace.

In 2021, there were 2,129 cases of opioid poisoning out of 1.7 million workers in Ontario, according to Ontario Health. Tradespeople, service industry professionals, healthcare, and office employees – all workers – along with customers and contractors that enter businesses can be affected. With such a wide reach, it makes sense that a workplace first aid kit would contain a naloxone kit.

“To me it’s a no-brainer,” says Stephanie Fizzard, a former harm reduction worker. “When you’re grabbing your first aid kit, you’re grabbing your defib[rillator], and you want to be prepared with everything you need to handle that situation.”

Making naloxone part of our workplace first aid kits should be standard – along with training on how to administer it.

About opioids

Opioids like fentanyl, oxycodone, heroin, and morphine, are drugs with pain-relieving properties that can induce euphoria and have significant potential for addiction. They can be prescribed medications, or they can be obtained or produced illegally. According to the Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse, synthetic opioids are fueling the opioid crisis. Fentanyl and fentanyl-like substances that are of non-pharmaceutical origin and are illegally manufactured are the most widely available opioids in Canada’s unregulated drug supply. These drugs increase the risk of drug toxicity deaths because they are extremely potent and can be fatal, even in small amounts. Often, unrelated classes of illegally manufactured drugs contain fentanyl in an effort to increase addiction potential, leading to opioid overdoses even in people who did not knowingly use opioids.

What an overdose might look like

Opioids can cause an overdose and symptoms may present as difficulty walking, talking, or staying awake. It may show up as:

- Blue or grey lips or nails

- Very small pupils

- Cold and clammy skin

- Dizziness and confusion

- Extreme drowsiness

- Choking, gurgling, or snoring sounds

- Slow, weak, or no breathing

- Inability to wake up, even when shaken or shouted at

How naloxone works

Naloxone is a medicine that blocks the effects of opioids – that’s why it’s known as an “opioid antagonist.” When opioids enter the body, they rapidly bind with opioid receptors. Naloxone blocks the effects of opioids by kicking the opioids off those receptors – and binding to those receptors itself.

Naloxone is not a treatment for opioid use disorder. It is used to temporarily reverse the effects of opioid overdoses. It can restore breathing within two-to-five minutes and is active in the body for 20-90 minutes, whereas the effects of most opioids last longer. In other words, the effects of naloxone are likely to wear off before the opioids are gone from the body, which causes breathing to stop again. Naloxone can be administered multiple times as needed until help arrives. If naloxone is administered to someone who is not overdosing on opioids there will be no ill effects. So, naloxone is a low-risk, high-yield treatment.

The effects of stigma

I remember the first time I was given a naloxone kit. I had surgery in 2018 and needed a course of narcotic pain medication. I practically threw the kit back on the counter. “I’m not a drug addict,” I spat back at the pharmacist. I was concerned about how I would be seen and resistant to the idea that a person like me could even need naloxone. I know much more now – that opioids can affect anyone of any walk of life. The stigma that surrounds substance use can spill over into the use of naloxone.

“A lot of people feel like they’re enabling substance use if they reverse an overdose,” says Fizzard, who is also a person with lived experience of substance use. “I tell them ‘You’re helping people breathe and stay alive – you’re not doing anything else; you’re not helping them take drugs.’”

Fizzard notes that public services have not kept pace with issues of opioid use and overdose, meaning there aren’t enough services out there to meet needs. She makes the case for everyone having awareness of and access to a naloxone kit – noting that the largest barrier to using naloxone is not administering the medication, but the stigma surrounding its use, including in the workplace.

How naloxone is administered

Naloxone comes in two forms: injectable and nasal spray. The injectable form can be intimidating if you are not accustomed to needles. The nasal spray is quick and easy, according to Fizzard.

“The nasal is much more user-friendly,” she says. “In a pinch, you just pull it out of the packaging, put it in the person’s nostril and push the button. Simple. There’s no way of messing it up.”

Naloxone at work

Naloxone is not mandated in the workplace across Canada. Ontario has laws, embedded in the Occupational Health and Safety Act, requiring businesses that employ people who are at risk of overdosing to keep naloxone on hand and train staff how to use it. However, this is only a partial mandate, as those businesses who determine that they do not “employ people at risk” are not required to provide naloxone at work.

In British Columbia, naloxone is not required in the workplace, but tools exist to help identify where it should be employed. In Alberta, employers can choose whether or not to authorize the use of naloxone in the workplace, but if they do then the employer and worker must comply with a set of requirements established by the government.

For workplaces in Canada, health and safety mandates are the jurisdiction of the provinces and territories, meaning that a Canada-wide mandate is not likely. Instead, provinces and territories will have to decide to overcome the stigma and challenges and legislate the inclusion of naloxone in the workplace individually.

Are there barriers to keeping naloxone in a kit at work? It has a shelf life of around two years (or until used) after which it would need to be replaced and repurchased at around $100 per kit; this could pose a challenge to some businesses. (Ontario is providing kits free to businesses, for a limited time, to ease this burden). There could be training costs and stigma is an additional barrier that may prevent workplaces from acquiring naloxone kits.

Your kit

For individuals, naloxone is free in many provinces and territories and is available at pharmacies over the counter, or by ordering online, without a prescription. Online tutorials demonstrate how to use the kits.

As workers, we can inquire whether a naloxone kit is available at work and, if not, whether a kit and training could be made available. Naloxone kits are small, easily stashed in any workplace, and take minimal training to use. In Ontario, it should be enough to identify oneself as a person at risk of overdosing to trigger the requirement that a kit be provided.

In sum, it’s simple: naloxone can save lives – but only if it is available and people are trained how to use it.

Infographic: Do Drugs Contain What We Think They Contain? (Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction)

Further reading: How compassionate health care can alter the trajectories of people who use substances.

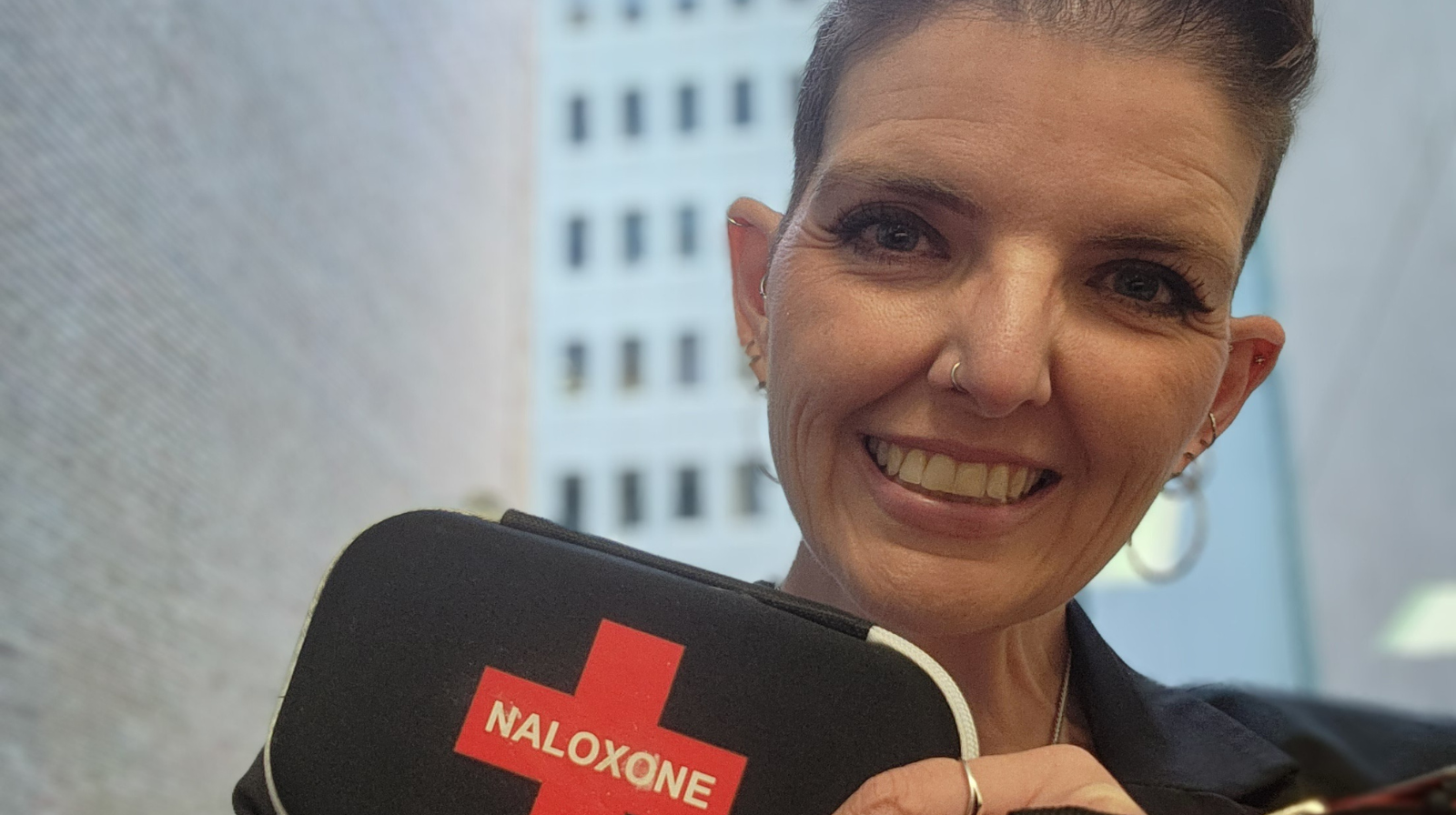

The author at the office with her workplace naloxone kit.

Jessica Ward-King

BSc, PhD, aka the StigmaCrusher, is a mental health advocate and keynote speaker with a rare blend of academic expertise and lived experience. Equipped with a doctorate in experimental psychology and firsthand knowledge of bipolar disorder, she’s both heavily educated and, as she likes to say, heavily medicated. Crazy smart, she’s been crushing mental health stigma since 2010.