Psychedelic-Assisted Therapy: What Is It?

Subscribe to Catalyst

Subscribe to get our magazine delivered right to your inbox

Related Articles

Related Articles

After 20 years of conventional treatment for depression, Toronto’s Kathleen Flynn decided it was time to look for alternatives, including psychedelic-assisted therapy.

“I was getting some benefit from my medication and therapy, but it wasn’t enough for me to be successful in my life,” says Flynn. “I was basically considered fine as long as I could get up, brush my teeth and go to work.”

Worse, she wasn’t even “fine” all the time. The regimen failed to protect her from periodic “mood dips” that sent her into clinical depression. When Flynn crashed again in late 2023, she felt “desperate enough to try something new” and opted for six sessions of ketamine-assisted therapy. Family helped her pay the nearly prohibitively expensive fee of $1,000 per session, which consisted of hour-long ketamine “trips” followed by therapy.

Ketamine, incidentally, is a “dissociative” anaesthetic with psychoactive effects, as opposed to an actual psychedelic substance, which may help explain why Flynn didn’t have any visions or striking revelations. What it did do was relax her in a way that seemed to make her more “fluid” with difficult emotions during therapy. Nearly a year later, she still thinks it was the right choice for her.

“It’s wild to say, but I was able to go off one medication and reduce another,” she explains. “I’m on the least amount of medication I’ve been on for over 15 years and I’m doing the best I’ve ever been doing.”

Perhaps you have heard of others investigating this field. While psychedelic-assisted therapy is gaining attention, this article is not meant to advocate for any specific treatment. Instead, it aims to explore the growing field, answer common questions, and examine the scientific, historical, and cultural contexts surrounding these therapies.

Dawning of an old era

Since people are more willing to tell success stories than failures, we may be hearing more of the good news stories than bad about psychedelic therapies from our friends and in the media. The reason this has captured peoples’ imaginations, though, is partly because a lot of folks are feeling stuck and, like Flynn, “desperate enough to try something new.”

To be accurate, however, very little of this is new. Indigenous cultures in the Americas, the first scientists on these continents, have studied the healing properties of plant medicines for millennia. Psychedelics are newer in western medicine, but psychedelic-assisted therapy (PaT) was developed in the 1950s in rural Saskatchewan, which is also the birthplace of the actual term “psychedelic,” a fun bit of Canadiana discovered by Erika Dyck, Canada Research Chair, History of Health & Social Justice at the University of Saskatchewan.

The word was first used by British-trained psychiatrist Dr. Humphry Osmond in a letter to his pal Aldous Huxley, author of Brave New World and The Doors of Perception. Huxley sometimes gets credit for the term, but it was Osmond who first combined two ancient Greek words that translate as “mind” and “revealing.”

At the time, Osmond was at a hospital in Weyburn, Saskatchewan, experimenting with treating patients with alcohol use disorder with a single large dose of Lysergic Acid Diethylamide (LSD) in combination with therapy. He’d been invited there in 1951 by provincial premier Tommy Douglas. “Osmond came over from England in this moment of ideological enthusiasm as part of (provincial) health reforms, including mental health,” notes University of Saskatchewan’s Dyck.

Douglas’ role as the “father of universal healthcare” in Canada is widely celebrated. Less well-known is the role he played in kick-starting psychedelic-assisted therapy, pioneered by Osmond and his colleague, Dr. Abram Hoffer. Since the results were promising, their work developing PaT inspired many similar research projects in what came to be known as the “Psychedelic Era.”

The era was destined to be brief. As psychedelic substances gained popularity outside of research circles and people began using drugs like LSD, psilocybin mushrooms, and mescaline for recreational, spiritual and/or self-healing purposes, psychedelics provoked societal anxiety and thus began their descent from panacea to pariah.

Psychedelics are neither of these things, of course, but it’s a class of drugs that invites extremes. Throughout the 1960s and early 1970s, the camp that fought to vilify and criminalize psychedelics succeeded in both the United States and Canada, which put the nail in the coffin of nearly all institutional psychedelic research.

Although this research is making a comeback in what some call the “Psychedelic Renaissance,” most of the drugs used in PaT remain illegal, including LSD, psilocybin mushrooms, mescaline, and methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA), the latter a stimulant that can cause hallucinations but isn’t technically a psychedelic. Only ketamine is legal because it’s used as an anaesthetic.

The legal prohibition on psychedelics presents special problems for researchers, who have multiple extra hoops to jump through to gain access to these medicines and ethics permissions for clinical trials.

“Psychedelics are still stigmatized from the war on drugs,” says Dr. Monnica Williams, Canada Research Chair in Mental Health Disparities at the University of Ottawa and author of Healing the Wounds of Racial Trauma. “And, because they’re illegal, people assume that must mean they’re really dangerous and addictive. And they’re not.”

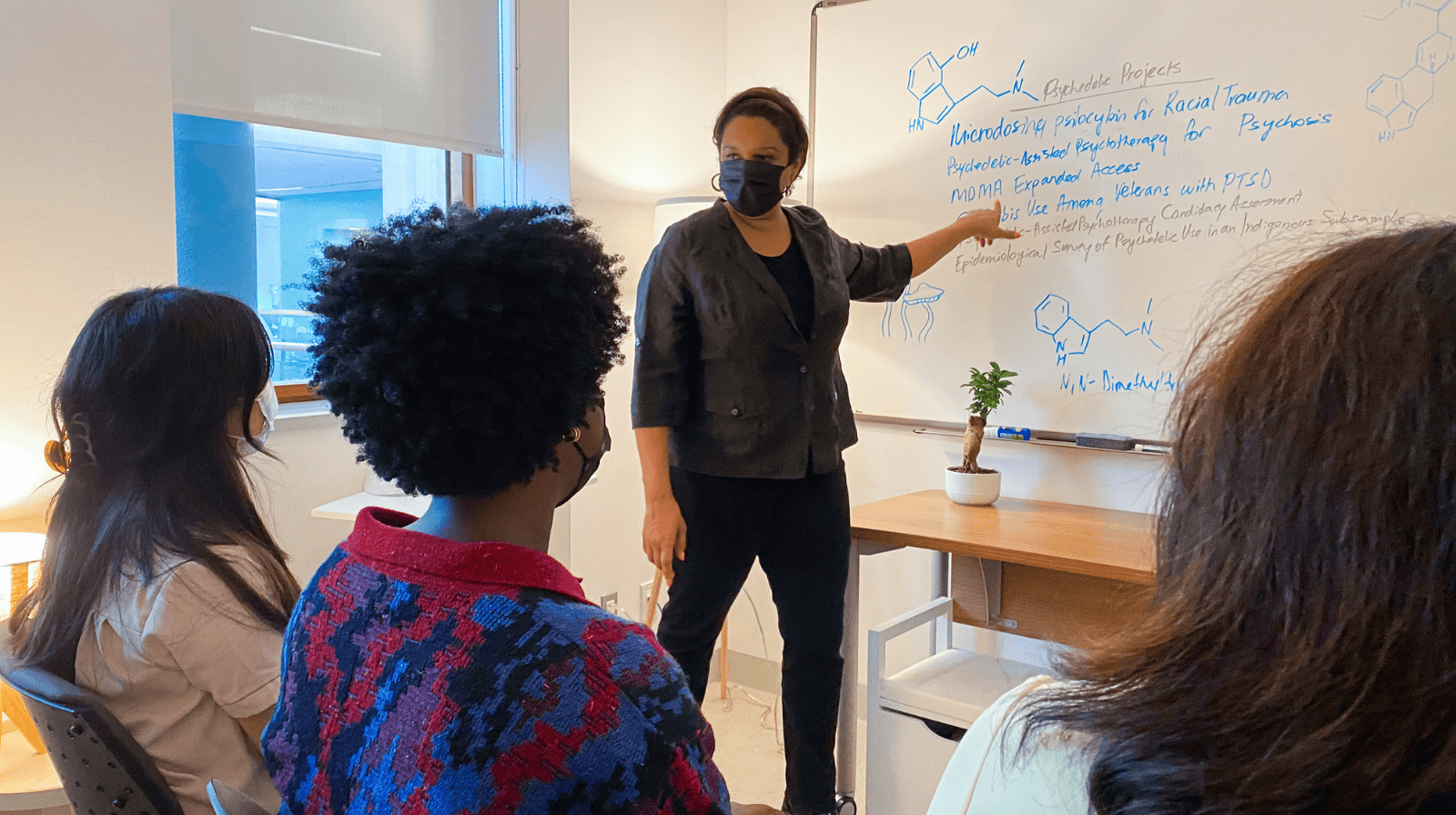

Dr. Monnica Williams is a clinical psychologist and Professor at the University of Ottawa, in the School of Psychology. Williams researches the use of psychedelics in treatment.

From counterculture to clinic

“Psychedelics are still stigmatized from the war on drugs,” says Dr. Monnica Williams, Canada Research Chair in Mental Health Disparities at the University of Ottawa and author of Healing the Wounds of Racial Trauma. “And, because they’re illegal, people assume that must mean they’re really dangerous and addictive. And they’re not.”

That’s a source of frustration for Williams, whose research interests include PaT as a treatment for people who’ve experienced intergenerational and race-based trauma. Both of these forms of trauma are poorly understood and under-researched and the people who experience these traumas are under-represented in clinical trials. “We know, based on epidemiological studies, that people of colour use psychedelics at a much lower rate than white people, which is one reason why there’s not been as much inclusion (of people of colour) in research studies,” explains Williams.

Many researchers in this burgeoning field, including Dr. Emma Hapke, Staff Psychiatrist, Toronto’s University Health Network and Associate Director, UHN Psychedelic Psychotherapy Research, argue that we need more diversity at all levels of the psychedelic ecosystem.

“The patients that are being recruited for the trials are predominantly…well, there’s this acronym, WEIRD, which stands for white, educated, industrialized, rich and, democratic,” says Hapke. “And so, it’s people with these privileged intersectional identities that end up in the trials.”

Lack of diversity in these trials limits the generalizability of the results to the wider population, making it harder for PaT to be approved by regulatory boards. Another issue that makes the pathway to becoming a legal regulated drug harder for a psychedelic substance than others is that the treatment isn’t just about the substance, it’s bundled with therapy. Drug regulators may know little about the therapy component, since the system is built for medicines designed to become, say, pills that make people better on their own. Within PaT, psychedelics are considered a catalyst. The real “work” is being done with the therapist before and after the trip.

“Psychedelic healing is not just about the chemical or the substance, it’s about the whole context,” says Amy Bartlett, a PhD candidate and researcher at the University of Ottawa. “I like to call it the ‘20-20-60 rule’. Twenty percent is the preparation, 20 percent is the journey, and 60 percent is what happens afterwards as we work to make sense of the experience and integrate the insights gained into our lives.”

While regulatory bodies often don’t have protocols for dealing with medicines that need to be situated in context, many Indigenous practices do. Dr. Dominique Morisano, a clinical psychologist and adjunct professor at the University of Toronto Dalla Lana School of Public Health and the University of Ottawa, says that some practices approach plant medicines and healing in a manner that is less focused on the individual and more focused on the collective, in contrast with typical Western medicine practices.

“Some Indigenous communities truly are integrated with a wide range of plant medicines and they collaboratively with and in connection to the plants in their environments,” says Morisano. “Plant medicines may be used not only as a way to heal the body, or the mind, or the spirit, but also as a way to seek ways to solve community problems, heal the collective or to support the planet we all live on.”

At the Naut sa mawt Collective for Psychedelic Research at Vancouver Island University, practitioners and researchers are trying to integrate the two different approaches to build out a new framework for PaT. It’s a trauma-informed approach that also addresses the issue of cultural appropriation that simply has to be dealt with in any serious conversation about moving forward with psychedelics.

This is clearly a step in the right direction, given that Articles 21 and 22 of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada call for “new Aboriginal healing centres to address the physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual harms caused by residential schools” as well as recognition of the “value of Aboriginal healing practices.”

Establishing the science to support PaT is, of course, important. Science doesn’t happen in a vacuum, though. It happens within a culture and, ideally, in a community.

So far, the (western) psychedelic space isn’t exactly known for inclusivity or equitable access. It’s high time to change the culture and grow the community. If the “renaissance” has any hope of living up to the great ideological enthusiasm of the Tommy Douglas years—and lasting longer than the first psychedelic era—it’s going to need all the different voices and perspectives it can get.

Fact Sheet: Psychedelics in Canada: An Overview.

Further reading: Common Mental Health Myths & Misconceptions

Photo: Dr. Monnica Williams. Her research interests include psychedelic-assisted therapy as a treatment for people who’ve experienced intergenerational and race-based trauma.

Author: Christine Sismondo, PhD, is a National Magazine Award-winning writer, author and columnist. Christine has been writing about history, health, and the importance of public spaces for national publications, including the Toronto Star and Maclean’s, for more than 20 years. Sismondo is also the author of America Walks into a Bar (Oxford University Press, 2011), and Prohibition, a six-part podcast for Wondery’s American History Tellers.