The Sounds and The Feels

Subscribe to Catalyst

Subscribe to get our magazine delivered right to your inbox

Related Articles

Related Articles

This piece is part of the Mental Health for the Holidays series. Our annual literary collection delves into various seasonal subtopics. We’re looking at good tidings, bad partings, and new traditions — things that emerge from estrangements, changes, and major shifts. While end-of-year celebrations can be joyful, they can also trigger feelings of stress and loss. Read the collection to learn how others were able to meet those challenges. Here’s a previous series on moping, coping, and hoping. Warm wishes for the holidays.

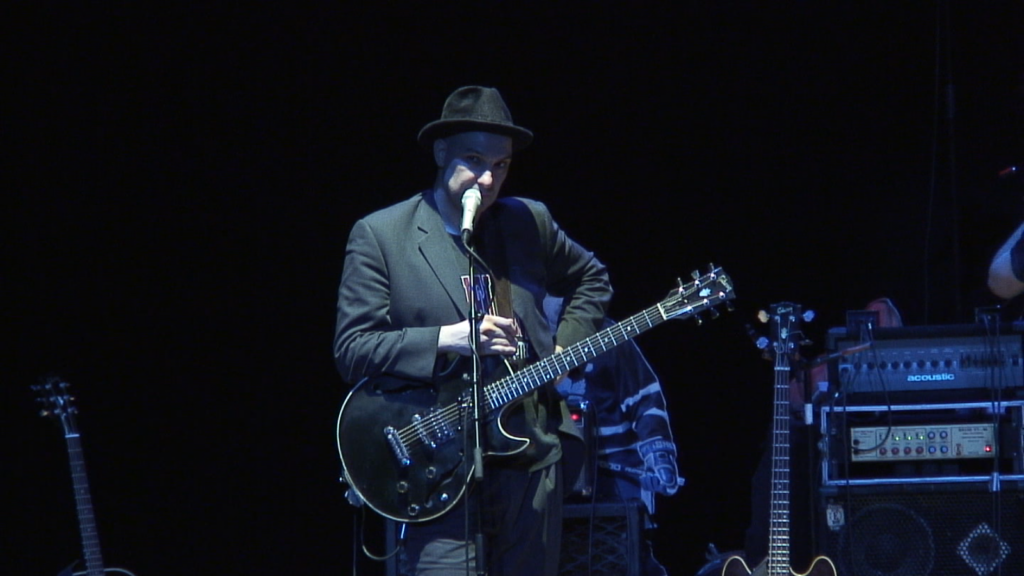

It’s been a long journey, this band. Rheostatics’ first show was in October 1980, at The Edge in Toronto and I remember the tears as often as I remember the screams of delight. It comes with the territory: the battles, the distress, the close-to-the-bone existence between four kids, who became four adults, who became four older adults. Scars heal and wounds mend, and the triumphs of shows, albums, and tours recede giving way to time passed, but the essence of simply surviving is the element that I stand behind lo these forty-plus years. Somehow, we made it.

For many musicians and people working in other disciplines, art gives us our point of emotional release. And with that release — with the doors of the heart flying open and the head swimming in an ocean of ideas and dreams — you’re never sure what will flow forward: ecstasy, anger, staggering bouts of laughter, and peals of distress. Being in a band is like playing in an endless field occasionally laid with mines and an unseen river of pathos. The hard times might not seem healthy, but they are, and the good times might feel like they’ll last forever, although anyone who’s experienced them long enough knows they will not.

Soul proprietor

Playing music with others means navigating, spiriting, and occasionally bartering with the depths of another person’s soul. If the art is any good it has to hurt a little coming up, and that vulnerability can be trying, even when it’s cresting over beautiful melodies created by someone you know closely and well. In Rheostatics, there was always the knife’s edge of nervous tension when a person brought in a new song. Minutes later, you’d be honouring and celebrating its existence by working hard to get it where it had to be, fully grown, but we were always aware of the author’s tender struggle to present it and bring it to life.

Still image from a video by Mark Sloggett.

“The sound of the crowd cheering came at me like a magnificent cloud of singing, crying birds. I’ll never forget it for as long as I live.”

We live, mostly, in a world where we’re taught to conform and suppress artistic expression— the greater forces of commercial society would have us behave “normally” rather than scream into a microphone at top volume with an army of friends raging behind you — but music and art dares your voice to be heard. As a mental health exercise, it leaves you happy and free, but as a social gesture, it’s still unsettling to many. There’s a clip I saw recently of Yoko Ono wailing over a Chuck Berry song performed on the Mike Douglas show, and its fearlessness left me staggered. It was pure release, pure voice, pure personality without a worry about how it would be processed by the host, the crowd, or the band. It was a sterling musical gesture; unencumbered by worry or comportment; unafraid by what anyone other than the singer would feel.

Playing in a band is easy. Playing in a band is hard. You have to learn how to get along, but you also have to learn to honour the release. Of course, there’s the functional and technical side about assembling a song so that it, more or less, makes sense, but the best times are when you’re on that wave and you’re unconscious of how or whether it’s working. The worst part is when others can’t find the wave, leaving the writer defeated, forlorn. But embracing failure is as important as achieving success. Not every song is going to create that shared feeling, but when it does: woah. You’re pulling people into your vulnerability and, if you’re lucky, you’re sharing it with dozens, hundreds, maybe thousands of strangers who are also pulled to it.

One time, during a performance at Massey Hall, I could feel all of these things happening — it was an ethereal moment, shroud in light and joy — and after the song ended, I told myself to stop and listen. The sound of the crowd cheering came at me like a magnificent cloud of singing, crying birds. I’ll never forget it for as long as I live.

Hello darkness, my old friend

With performers, there’s always darkness married to the light and, in the ‘90s, I recall, that darkness was rarely acknowledged as something to be addressed, wrestled with, and met head on. If someone had a worrying performance, or behaved worryingly, we lapsed into the mythology that the person was merely artistically petulant or troubled; they were bearing an artist’s soul through the difficult process of making good art. But recent musicians from Menno Versteeg of Hollerado to Kendrick Lamar to Big Boi of OutKast have been bold faced in recognizing the unhealthy environment in which so many musicians exist: endless touring hours, booze delivered nightly into your dressing rooms, unhinged schedules, the pressure to be better than your last creation, a stigma that haunted Van Halen’s Eddie Van Halen to his last days.

The signs of struggle are clearer now than they’ve ever been to the point that musicians are more aware of the demons, and fans tilt on the side of forgiveness rather than wanting their favourite bands to be wild and raw at all costs. People like Miranda Mulholland have advocated for venues with more non-alcoholic products, and, at the West End Phoenix newspaper storefront where we hold shows, we’ve staged “sober” gigs without alcohol sales. It’s taken generations, but we finally understand the danger and absurdity of an occupation where, the moment you show up for work, a tray of iced Bud is laid at your feet. We had — and continue to have — a great career, but I wonder if we could have fought through the hard gigs if we weren’t often relying on booze to get us to the end. But that scar has also healed.

Surviving has allowed us to look back at this life, this career, in the fullness of its landscape, but that’s not to suggest that, for newer musicians, it has to be the same. Maybe the cover has been torn off the facade; the seal removed from the prescription. Maybe now it doesn’t have to be as rough and dangerous as it is smooth and beautiful. Maybe you can get near the end without feeling you’ve paid too much for it.

Further reading: Common Mental Health Myths and Misconceptions.

Resource: How Alcohol and Suicide are connected – A Fact Sheet.

Author: Dave Bidini, has had countless sobering realizations as publisher of the West End Phoenix community newspaper in Toronto. He has so many favourite songs.