Tough Talk

Subscribe to Catalyst

Subscribe to get our magazine delivered right to your inbox

Related Articles

Subscribe to Catalyst

Subscribe to get our magazine delivered right to your inbox

Share This Catalyst

Related Articles

There is no strong silent type when it comes to men’s mental health

By Michel Rodrigue

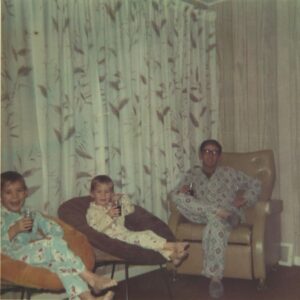

Michel Rodrigue, left, enjoying a soft drink (a treat!) in preparation for the hockey game – the Montreal Canadiens, of course.

Long before I knew what mental health was, I knew that men didn’t talk about it. Certain topics were simply off the table, with deep personal feelings heading the list. To talk about those things would be unnatural, unwelcome, and uncomfortable — not to mention unmasculine.

It was only later, when I learned the concept of stigma, that I understood the truth. When men stay silent, it hurts everyone, most of all themselves.

Of the roughly 4,000 suicide deaths in Canada each year, 75 per cent are men. For men between the ages of 15 and 39, suicide is the second leading cause of death (after accidental death). Clearly, we have a lot to talk about.

Stigma breeds silence

My father worked in construction most of his life. In his all-male crew, if someone was injured on the job, the first aid response was unflinching. There was no hesitation about doing or saying the wrong thing. There was no reassessment of that person’s masculinity or judgment of their character. Everyone understood the reality — that it could have happened to any of them.

In the same way, no one is immune to mental illness. Yet, if someone would have had a panic attack on the job site, I suspect the response would have been entirely different. That’s stigma at work.

But there’s another feature that sets mental illness apart — it’s invisible.

We can see the limp of an injured leg or read the temperature of a fever. Mental health problems, on the other hand, often hide in plain sight. —

I learned this the hard way when I lost a close friend to suicide.

From the outside looking in, Sylvain had everything to live for. A loving wife, two beautiful daughters, a caring family, close friends, and a thriving business. At least, that’s what we thought.

It was only after his death by suicide in May 2005 that we learned he’d been pretending to go to work for many months.

I try to imagine what that time must have been like for him. How ashamed and embarrassed he must have felt to keep that secret so closely guarded. I think about the role stigma played in his death. And I think about how much work we still have ahead of us, especially men.

Turning insights into action

In my seven years with the Mental Health Commission of Canada, I’ve learned a lot about men’s mental health. I’ve learned about the growing evidence of a distinct male-type depression, characterized by externalizing symptoms such as irritability, anger, and substance use.

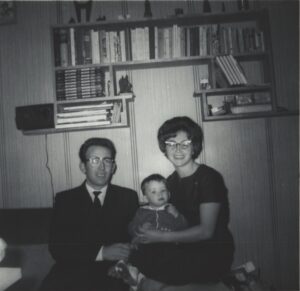

A young Michel with his parents Lionel and Lucille.

I’ve learned that while loneliness, substance use, and depression are among the strongest risk factors for suicidal behaviour in men, other factors put certain subgroups at an even higher risk. For example, the rates of attempted suicide for First Nations, Inuit, and Métis who identify as sexual and/or gender minority men (including gay, bisexual, men who sleep with other men, and transmen) are up to 10 times as high as for men in this group who are non-Indigenous.

But perhaps the most important thing I’ve learned is that, as men, we need to get comfortable being uncomfortable. Talking honestly about our mental health is one of the best ways we can protect it, no matter how unnatural it might feel at first.

At best, the cost of silence is isolation, even in the company of other people who would willingly offer their support. At worst, that silence can cost a life. It’s time for all men to embrace the discomfort, break through the masculine ideals, and leave nothing off the table.

Michel Rodrigue is president and chief executive officer of the Mental Health Commission of Canada.

Michel Rodrigue