If you are in distress, you can call or text 988 at any time. If it is an emergency, call 9-1-1 or go to your local emergency department.

- Fact sheets, Professional Resources

Agriculture and Suicide Fact Sheet

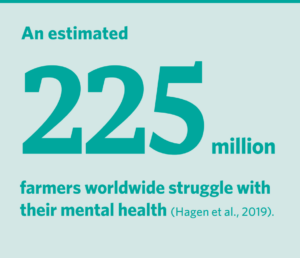

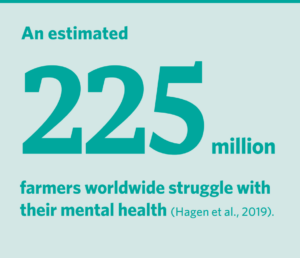

This resource was published in 2022. The data may be out of date. Farming and ranching are considered two of the most stressful occupations, both physically and mentally. Unique factors associated with agricultural work may contribute to poor mental health outcomes and even suicide. In Canada, producers (farmers and ranchers) are especially prone to mental health challenges such as depression and anxiety, and they may have less resiliency because of the stressors they experience (Jones-Bitton et al., 2020). While much of the research on resiliency focuses on farmers specifically, some of the factors farmers face are similar to what other producers may face. Certain factors can place some people at a higher risk for suicide than others, and when multiple risk factors outweigh the factors that build resiliency, there is an increased likelihood that a person may think about suicide (Sharam et al., 2021).

Why are farmers at risk?

What can communities do to help reduce suicide among farmers?

- Fact sheets, Professional Resources

Agriculture and Suicide Fact Sheet

Agriculture and Suicide Fact Sheet

- Suicide Prevention

This resource was published in 2022. The data may be out of date. Farming and ranching are considered two of the most stressful occupations, both physically and mentally. Unique factors associated with agricultural work may contribute to poor mental health outcomes and even suicide. In Canada, producers (farmers and ranchers) are especially prone to mental health challenges such as depression and anxiety, and they may have less resiliency because of the stressors they experience (Jones-Bitton et al., 2020). While much of the research on resiliency focuses on farmers specifically, some of the factors farmers face are similar to what other producers may face. Certain factors can place some people at a higher risk for suicide than others, and when multiple risk factors outweigh the factors that build resiliency, there is an increased likelihood that a person may think about suicide (Sharam et al., 2021).

Why are farmers at risk?

What can communities do to help reduce suicide among farmers?

SHARE THIS PAGE

RELATED

Review our Assessment Framework for Mental Health Apps — a national framework containing key standards for safe, quality, and effective mental health apps in Canada.

To help expand the use of e-mental health services, we developed four online learning modules based on our Toolkit for E-Mental Health Implementation, in collaboration with the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH).

Stepped Care 2.0© (SC2.0) is a transformative model for organizing and delivering evidence-informed mental health and substance use services.