If you are in distress, you can call or text 988 at any time. If it is an emergency, call 9-1-1 or go to your local emergency department.

- Reports, Research

The Aspiring Workforce: Employment and Income for People with Serious Mental Illness

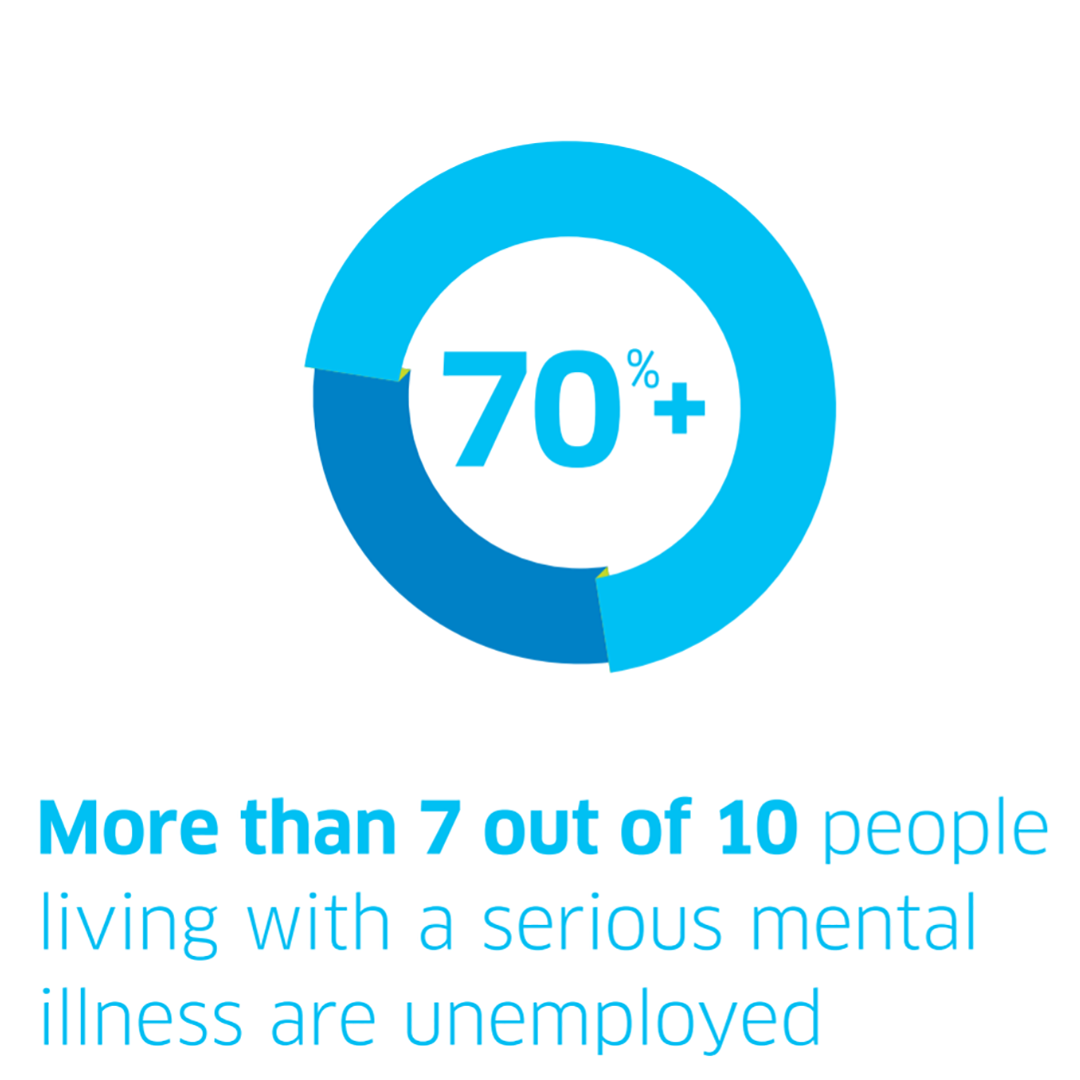

A disproportionate number of people with serious mental illness in Canada are unemployed or detached from the labour market, and the numbers of people with mental illness transitioning onto disability income support programs are rising. Many of our current ways of thinking about the work capacity of people with mental illness, and acting upon the problem, are ineffective. Systemic forces can lead to the employment marginalization of people who have skills and expertise to contribute to the Canadian economy and workforce. We urgently need a national program of action to change this situation. There are effective ways to increase employment; this is a problem that has solutions. There is no one answer, but instead, a system of responses is required to effectively improve this issue. In September 2009, the Mental Health Commission of Canada contracted the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health to undertake “The Aspiring Workforce” research project, in collaboration with researchers from the University of Toronto and Queen’s University. The intent of the project is to identify existing and innovative practices that will help people living with serious mental illness to secure and sustain meaningful employment and/or a sustainable income. The term “Aspiring Workforce” describes those people who, due to mental illness, have been unable to enter the workforce, or who are in and out of the workforce due to episodic illness, or who wish to return to work after a lengthy period of illness. These people are as diverse as other Canadians in their life experiences and identities and come from all regions and cultural and linguistic groups across Canada. But, like any other Canadian, they share a desire and need for meaningful employment and a sustainable income. Canadians living with significant mental health issues experience high rates of unemployment. The “Aspiring Workforce” project is built on the understanding that access to work and to disability income support are intricately related for people with significant mental illnesses. Evidence from research shows that access to work can be improved through the use of supported employment programs. Supported employment is often provided by a variety of mental health professionals to help people find work that they are interested in, in the regular labour force, with ongoing support to help people within their jobs. Beyond supported employment, there are a variety of innovative approaches to creating employment opportunities. A good example of this is the social business approach, which uses market strategies to create jobs for people with serious mental illness. By marketing quality goods and services to the Canadian public, social businesses provide an avenue to increase the profile of the aspiring workforce as contributing and capable. Disability income benefits provided by a range of governments (federal, provincial, and territorial) and private providers are also important. Many people from the “Aspiring Workforce” may need to move in and out of the workforce and onto benefits due to the episodic nature of their mental health problems. Developing programs that are flexible and coordinated is important to ensure that people have a living income, whether from disability benefits, employment income, or a combination of these sources. Entering the workforce often has a spider web effect on financial and other supports – once people begin to work, they can experience clawbacks in their disability income assistance, they may lose their health care benefits, and their rent may increase if they participate in a rent-geared-to-income program or receive rent subsidies. If they need to stop working, it may take long periods of time to undo the effects that working has caused on their benefit eligibility, placing them at risk of homelessness, or in other precarious situations. • People with a job are healthier, have higher self-esteem and have higher standards of living. • Randomized controlled trials tell us that people with mental illness who work use far fewer hospital and other health services than those without employment. • A lack of work has been linked to stress and psychological instability, problems with self-esteem, relational conflicts, substance use, and other more serious mental health concerns. The right employment supports – Not all employment supports are equal. The evidence tells us that rapid job placement models with long-term help to maintain employment are more successful and cost-effective than pre-vocational activities. Supported employment is an Alternative employment options – Social enterprise has a track record of creating meaningful employment for people with mental illness. These businesses are often owned and operated by those who have received mental health services. The right incentives – Well designed government programs can promote independence. People receiving social assistance and disability supports who work should not be subject to punishing disincentives. Working should make economic sense. The right information – Arming people with mental illness who want to work with the knowledge of the rights and supports they have access to in the workplace leads to a greater chance of success. A paradigm shift de-stigmatizing people with serious mental illness Collaboration among different sectors Use existing best practices while continuing to innovate Early intervention System capacity building Knowledgeable consumersThis resource was published in 2013. The data may be out of date.

Executive Summary

The Problem

We Know That…

• There is overwhelming evidence that most people with serious mental health problems have skills and expertise to offer to the labour market – they can work, and want to work.The Economic Cost

• Approximately $28.8 billion is spent each year in disability income support.

• Increasing employment will greatly reduce these costs.The Human Cost

• Unemployment is associated with a twofold to threefold increased relative risk of death by suicide, compared with being employed.

• Mental health consumers, families, and clinicians can testify to the impact of employment on health and wellbeing.The Answers

innovative rapid job search model that has proven very effective.Recommendations

We need to re-conceptualize the relationship between work and mental health consumers.

As the issue at hand spans multiple ministries and multiple stakeholders/actors, the importance of partnership and coordination is integral to the process of increasing labour market attachment for people with mental illness. Federal and provincial governments, mental health service providers, community organizations, and employers, and people with mental illness themselves, all need to be at the table moving forward.

Removing disincentives to return to work

Our current income support systems create barriers, with few incentives for returning to work. Those receiving disability income supports fear exiting these programs – once a person begins to work, their financial situation may become precarious and can actually worsen. We need to ensure there is sufficient incentive in returning to work, allowing disability income support programs to serve as a safety net. We also need to make it easier to find information about employment benefits available through disability income support programs.

There are best practices and we should use them. We know supported employment works, and there is growing evidence of the potential of social businesses – but access to these opportunities is limited and they need more and stable funding. A commitment to invest in the development and testing of new strategies is also required.

The longer a person spends away from the labour market, the more difficult it is to return. We need to ensure supports are offered early, to reduce long-term detachment and encourage career development.

Compared to other OECD countries, Canada ranks 27th of 29 countries surveyed on public spending for disability-related issues and provides the second to lowest compensation and benefit levels. Reforms will require additional resources and funding in order to effectively expand labour force participation. This is not only beneficial for the success and wellbeing of those with mental illness – there is also a cost-benefit to putting resources into the right employment supports.

The Aspiring Workforce (AW) study seeks to identify ways of helping consumers become workplace savvy. We acknowledge that success requires both the employee and employer to be on board. Interventions discussed in the AW project address the needs of both.

- Reports, Research

The Aspiring Workforce: Employment and Income for People with Serious Mental Illness

The Aspiring Workforce: Employment and Income for People with Serious Mental Illness

- Workplace Mental Health

A disproportionate number of people with serious mental illness in Canada are unemployed or detached from the labour market, and the numbers of people with mental illness transitioning onto disability income support programs are rising. Many of our current ways of thinking about the work capacity of people with mental illness, and acting upon the problem, are ineffective. Systemic forces can lead to the employment marginalization of people who have skills and expertise to contribute to the Canadian economy and workforce. We urgently need a national program of action to change this situation. There are effective ways to increase employment; this is a problem that has solutions. There is no one answer, but instead, a system of responses is required to effectively improve this issue. In September 2009, the Mental Health Commission of Canada contracted the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health to undertake “The Aspiring Workforce” research project, in collaboration with researchers from the University of Toronto and Queen’s University. The intent of the project is to identify existing and innovative practices that will help people living with serious mental illness to secure and sustain meaningful employment and/or a sustainable income. The term “Aspiring Workforce” describes those people who, due to mental illness, have been unable to enter the workforce, or who are in and out of the workforce due to episodic illness, or who wish to return to work after a lengthy period of illness. These people are as diverse as other Canadians in their life experiences and identities and come from all regions and cultural and linguistic groups across Canada. But, like any other Canadian, they share a desire and need for meaningful employment and a sustainable income. Canadians living with significant mental health issues experience high rates of unemployment. The “Aspiring Workforce” project is built on the understanding that access to work and to disability income support are intricately related for people with significant mental illnesses. Evidence from research shows that access to work can be improved through the use of supported employment programs. Supported employment is often provided by a variety of mental health professionals to help people find work that they are interested in, in the regular labour force, with ongoing support to help people within their jobs. Beyond supported employment, there are a variety of innovative approaches to creating employment opportunities. A good example of this is the social business approach, which uses market strategies to create jobs for people with serious mental illness. By marketing quality goods and services to the Canadian public, social businesses provide an avenue to increase the profile of the aspiring workforce as contributing and capable. Disability income benefits provided by a range of governments (federal, provincial, and territorial) and private providers are also important. Many people from the “Aspiring Workforce” may need to move in and out of the workforce and onto benefits due to the episodic nature of their mental health problems. Developing programs that are flexible and coordinated is important to ensure that people have a living income, whether from disability benefits, employment income, or a combination of these sources. Entering the workforce often has a spider web effect on financial and other supports – once people begin to work, they can experience clawbacks in their disability income assistance, they may lose their health care benefits, and their rent may increase if they participate in a rent-geared-to-income program or receive rent subsidies. If they need to stop working, it may take long periods of time to undo the effects that working has caused on their benefit eligibility, placing them at risk of homelessness, or in other precarious situations. • People with a job are healthier, have higher self-esteem and have higher standards of living. • Randomized controlled trials tell us that people with mental illness who work use far fewer hospital and other health services than those without employment. • A lack of work has been linked to stress and psychological instability, problems with self-esteem, relational conflicts, substance use, and other more serious mental health concerns. The right employment supports – Not all employment supports are equal. The evidence tells us that rapid job placement models with long-term help to maintain employment are more successful and cost-effective than pre-vocational activities. Supported employment is an Alternative employment options – Social enterprise has a track record of creating meaningful employment for people with mental illness. These businesses are often owned and operated by those who have received mental health services. The right incentives – Well designed government programs can promote independence. People receiving social assistance and disability supports who work should not be subject to punishing disincentives. Working should make economic sense. The right information – Arming people with mental illness who want to work with the knowledge of the rights and supports they have access to in the workplace leads to a greater chance of success. A paradigm shift de-stigmatizing people with serious mental illness Collaboration among different sectors Use existing best practices while continuing to innovate Early intervention System capacity building Knowledgeable consumers

This resource was published in 2013. The data may be out of date.

Executive Summary

The Problem

We Know That…

• There is overwhelming evidence that most people with serious mental health problems have skills and expertise to offer to the labour market – they can work, and want to work.The Economic Cost

• Approximately $28.8 billion is spent each year in disability income support.

• Increasing employment will greatly reduce these costs.The Human Cost

• Unemployment is associated with a twofold to threefold increased relative risk of death by suicide, compared with being employed.

• Mental health consumers, families, and clinicians can testify to the impact of employment on health and wellbeing.The Answers

innovative rapid job search model that has proven very effective.Recommendations

We need to re-conceptualize the relationship between work and mental health consumers.

As the issue at hand spans multiple ministries and multiple stakeholders/actors, the importance of partnership and coordination is integral to the process of increasing labour market attachment for people with mental illness. Federal and provincial governments, mental health service providers, community organizations, and employers, and people with mental illness themselves, all need to be at the table moving forward.

Removing disincentives to return to work

Our current income support systems create barriers, with few incentives for returning to work. Those receiving disability income supports fear exiting these programs – once a person begins to work, their financial situation may become precarious and can actually worsen. We need to ensure there is sufficient incentive in returning to work, allowing disability income support programs to serve as a safety net. We also need to make it easier to find information about employment benefits available through disability income support programs.

There are best practices and we should use them. We know supported employment works, and there is growing evidence of the potential of social businesses – but access to these opportunities is limited and they need more and stable funding. A commitment to invest in the development and testing of new strategies is also required.

The longer a person spends away from the labour market, the more difficult it is to return. We need to ensure supports are offered early, to reduce long-term detachment and encourage career development.

Compared to other OECD countries, Canada ranks 27th of 29 countries surveyed on public spending for disability-related issues and provides the second to lowest compensation and benefit levels. Reforms will require additional resources and funding in order to effectively expand labour force participation. This is not only beneficial for the success and wellbeing of those with mental illness – there is also a cost-benefit to putting resources into the right employment supports.

The Aspiring Workforce (AW) study seeks to identify ways of helping consumers become workplace savvy. We acknowledge that success requires both the employee and employer to be on board. Interventions discussed in the AW project address the needs of both.

SHARE THIS PAGE

RELATED

Review our Assessment Framework for Mental Health Apps — a national framework containing key standards for safe, quality, and effective mental health apps in Canada.

To help expand the use of e-mental health services, we developed four online learning modules based on our Toolkit for E-Mental Health Implementation, in collaboration with the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH).

Stepped Care 2.0© (SC2.0) is a transformative model for organizing and delivering evidence-informed mental health and substance use services.