A Name and a Face

Subscribe to Catalyst

Subscribe to get our magazine delivered right to your inbox

Related Articles

Subscribe to Catalyst

Subscribe to get our magazine delivered right to your inbox

Share This Catalyst

Related Articles

Mental illness, homelessness, and a family’s years-long search for their lost brother.

Wendy Hill-Tout doesn’t like being in the spotlight, but that’s where she finds herself these days. With her new documentary, Insanity, she shines a light on families coping with the severe and persistent mental illness of a loved one lost to homelessness. Sharing the camera’s attention are her siblings, who recount their lives with their brother, Bruce, as he struggled with schizophrenia until his disappearance 25 years ago.

Wherever the Canadian filmmaker’s North American travels take her, she searches the faces of unhoused people, looking for her brother. The photos she carries, bearded and clean-shaven, are shown to anyone who might recognize him. Her quest brings her to the alleys and tent cities that have become points of refuge for those the system has failed. The various homeless encampments the film documents show the scale of the problem and make it clear that Bruce’s face is just one among so many others.

Insanity shares the stories of families caught up in a system that doesn’t support individuals who are either not sick enough to get help or unable to access support while they are housed. In one example, Shirley Chan, a board member for the Pathways Serious Mental Illness Society, has desperately been trying to find the right support for her daughter. After being told that she was “too high functioning” to qualify for housing with the 24-hour support she needed, Chan discovered that the only way to obtain it was to refuse to bring her home the next time she was discharged from the hospital. Her daughter had to be homeless to become a priority.

Another instance shows Tyler, the youngest brother of Kristin Booth, a colleague Hill-Tout met while working on a different film. Tyler had been living on the street in Ontario when he was arrested after suffering a manic episode. Six weeks later, while on probation and living on his mother’s property, Booth recounts the trauma of lying to her brother to keep him on the premises so the Toronto police could collect him. Her voice cracks as she recounts the guilt of having to watch him be cuffed and taken away, breaking down at the impossible situation she found herself in. Even with the support of a lawyer and physician, she still couldn’t get Tyler the help he needed.

“What do other families do?” Karen Booth, Kristin’s mother, asks. Her doctor, who can find no other solution, tells her, “Mrs. Booth, if it wasn’t for you, Tyler would be either be dead or under a bridge — or in prison. That’s just the way it is.” But she refuses to accept that.

Hill-Tout delicately weaves these stories into the film to illustrate how easy it is for someone living with mental illness to end up on the street or get caught up in the criminal justice system. As she says during our Zoom interview while in Calgary, it is unacceptable that so many people are without help in a wealthy nation like Canada.

Wendy Hill-Tout

“Our system needs a major overhaul,” she says. “The first step would be to increase mental health care spending from where it’s at [seven per cent of total health-care spending] to 10 per cent like in European countries. We need to create more community mental health services to help people with mental health concerns before they’re in crisis. Imagine if we had specialized mental health clinics, so people would have somewhere they knew they could go and speak with specially trained doctors and nurses to connect them with appropriate services. Why is it the default to go straight to the hospital or ask someone in crisis to wait six months for services?” she asks.

Other issues to address include the lack of psychologists and psychiatrists, supportive housing, and access to services, Hill-Tout notes, adding that Canada needs to start somewhere, and increasing mental health funding is a good place to get the ball rolling.

What shocked her most during the project was how much more pronounced the problem became in a short time. “When we began filming in 2019, we would go to a city and hope to find someone on the street to show Bruce’s photo to. But before long, we were being confronted with tent cities — and it was happening everywhere — not just in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. The number of people on the street increased in both big and smaller cities.

“We need to do something urgently because we can change this,” she says with quiet conviction. “Instead of spending money on policing the problem, we should prevent it. So many people with mental illness are one breakdown from becoming homeless. How do you get back into housing once you’ve lost it? We need more community services along the way to prevent this from happening in the first place.”

She hopes that her documentary reaches the right people in government who have the power to enact the needed change, whether they’re municipal, provincial, or federal officials. This issue impacts more than one in five people who will experience a mental health problem during their life. It also spreads out across friends and families, and they’re the reason she made this film.

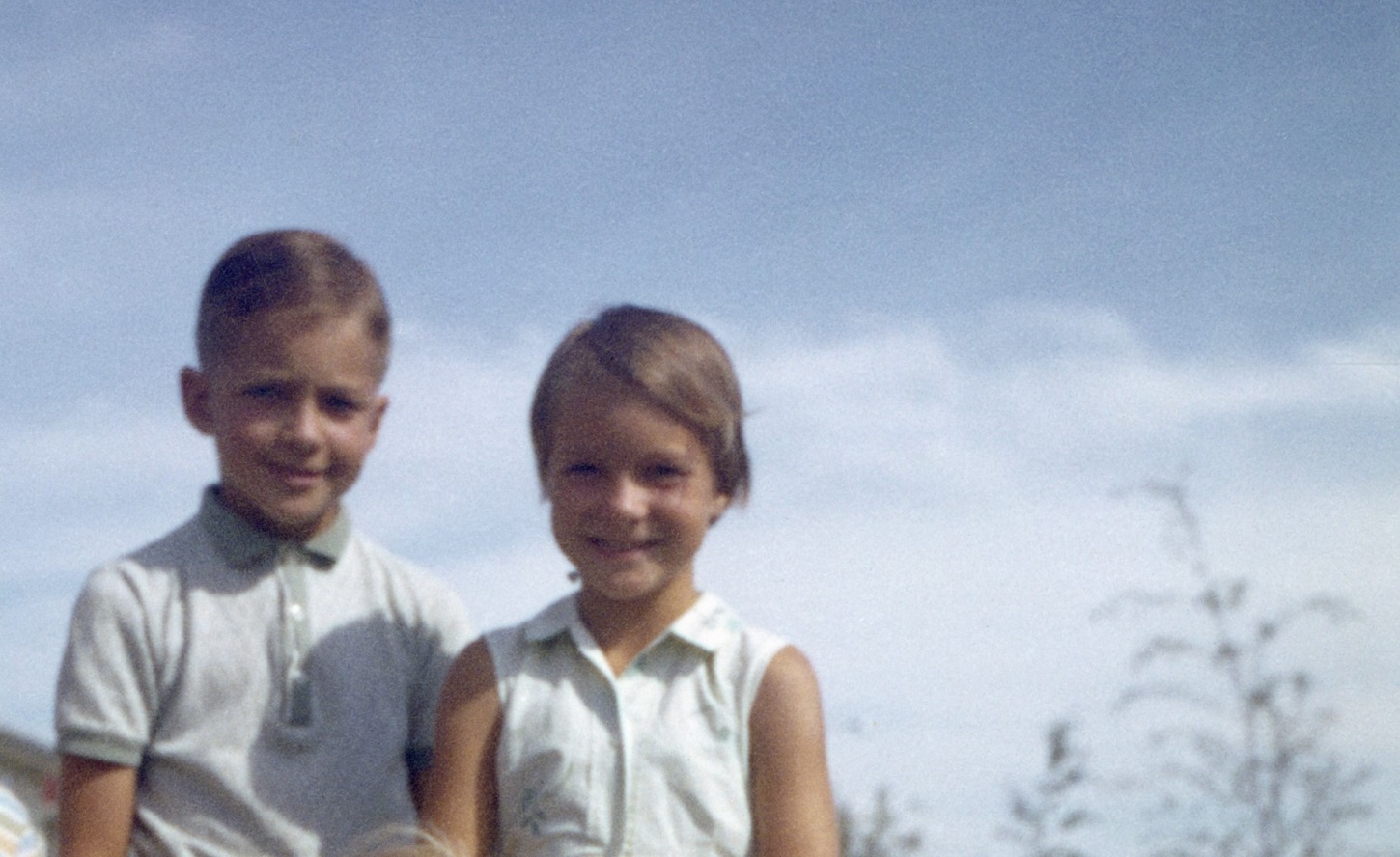

“It still surprises me how raw it is to talk about Bruce even after 25 years,” Hill-Tout says, toward the end of our time together. That emotion is also apparent in the film as her siblings share touching stories about their brother. They laugh together, but their memories have an undercurrent of sadness. And through their accounts, we learn that Bruce was the eldest of four children, thoughtful, funny, and warm-hearted, as well as being an artist and a bit of a daredevil at times.

“Bruce was the best person I’ve ever known,” her brother David said, “He was a really great big brother, and he’s worth fighting for.”

As hard as it is to revisit what led to Bruce’s disappearance, it’s important to put a name and face to the problem. Once society sees the people the system has failed as individuals loved and missed by their families, they are more inclined to push for change. Society is more likely to care for them.

It’s not all bad, though, as Hill-Tout points out. Some things give her hope for the future. For one, a greater general awareness of mental health and illnesses exists. The press now reports on people experiencing homelessness and how cities are handling the issue. There are also more police officers and first responders taking training on how to handle mental health calls. As well, there are more mobile mental health crisis units like Car 87 in British Columbia (compared to 10 years ago) — although these units cannot keep up with the current demand, so increased funding is still needed.

In the meantime, Hill-Tout and her family remain hopeful that they’ll find Bruce. She continues to search faces for one she’ll recognize after so many years. Maybe an audience member will recognize him after watching the documentary. Either way, her final message to me is the same one repeated in the film.

“Bruce, you are loved.”

Insanity will play at select screens in theatres nationwide starting May 11, 2023, with Q&As from Hill-Tout and other families featured in the documentary. Get more information and find out if it’s coming to a theatre near you at www.insanitydoc.com.