Subscribe to Catalyst

Subscribe to get our magazine delivered right to your inbox

Related Articles

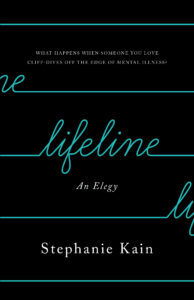

What happens when someone you love cliff-dives off the edge of mental illness?

This question appears on the cover of Stephanie Kain’s novel-memoir Lifeline: An Elegy (ECW Press, October 2023). Kain answers that and other questions over 210 pages of prose, text exchanges, short stories, and essays.

The book is stunning in its fragmented format, befitting the author’s experience of grappling with a frayed healthcare system, one’s own perspectives and biases, the mental illness of a loved one, and daily life challenges during the emergency phase of the pandemic.

The book is stunning in its fragmented format, befitting the author’s experience of grappling with a frayed healthcare system, one’s own perspectives and biases, the mental illness of a loved one, and daily life challenges during the emergency phase of the pandemic.

Complicated romantic, platonic, and familial relationship dynamics are named and noted with dry wit and underscored with pop culture references and lyrics (Shawn Mendes, Sara Bareilles, and Mumford & Sons, among them).

In Lifeline, advocating for one’s care is “Shirley MacLaine-ing” in a reference to Terms of Endearment. In a notable scene from that film, you hear a frustrated bellowing of, “It’s after 10!” as MacLaine’s character nearly has a breakdown at the triage desk trying to get her daughter a pain shot. Her pleading eventually works, and the volume and tone suddenly change. “Thank you,” she tells the nurse just above a whisper.

Kain has similar moments of raw reality. The story centres around the author’s complicated relationship with a woman diagnosed with suicidal depression. Kain writes about the indignities of a locked ward, having to administer heavy medications, supporting someone through the after-effects of electro-convulsive therapy, and her own well-being. The author – a creative writing professor at the University of Ottawa – spends time in PEI, and the island figures prominently as she looks to find a way forward.

The book’s format is jaunty and compelling, and its portrayal of the frustrations and realities of helping a loved one through mental illness is done with intensity and honesty – yet free of judgement and stigma, the things that can hold people back from seeking care.

The insomnia is camped out permanently like an adult child moving home for quarantine, knowing you can’t kick it out, even if it’s on its worst behaviour.

A chapter called Eight Things I’m Putting in Your Care Package offers insight as the author rationalizes each choice.

Multicoloured Pens: Blue and black are depressing as f–k, and since you hate any pencil crayons that aren’t your top-of-the-line artist brand, I’m not even going to try sending you any. Instead, you can draw with multicoloured pens and stop judging yourself and your work because nobody expects drawings made with multicoloured pens to be good. They’re just supposed to pass the time.

You might not recall because #Depression, but the last time you were in there, you made something in art class and spent half an hour criticizing it before I finally screamed at you that you were in a psychiatric hospital and the art wasn’t supposed to be good for the love of f–k and maybe this was the problem!

In this way, the book made me think about portrayals of mental illness in contemporary fiction. The Mental Health Commission of Canada’s magazine, The Catalyst: Conversations on Mental Health, has a section dedicated to this topic called Representations. It takes on popular narratives of mental well-being to mark their shifts. If you’ve watched One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest or Thirteen Reasons Why, you can see there is room for improvement with regard to nuance, honest portrayals, and false notions.

I was inspired to start this feature after reading a series in The Walrus reflecting on problematic classic works. This re-examination brings to light the ways in which society and literature have changed. Author Myra Bloom looks at the darker side of Leonard Cohen through a re-examination of Beautiful Losers’ stereotypes with discussions on the genius myth and what historian Martin Jay calls the “aesthetic alibi” used to justify bad behaviour. Writing about The Unbearable Lightness of Being, Amanda Perry says, “At seventeen, I could still assume beautiful phrases were true ones and take characters as guides for living.” Perry reflects on “the male writers whose words have shaped my psyche and whether it’s time to shake them off.”

Stephanie Kain

Reading that sentence, I think of depictions of mental health that live in my psyche. I grew up listening to The Ramones, whose many titles send up mental wellness (“I Wanna Be Sedated,” “Go Mental,” “Mental Hell,” “I Wanna Be Well” – I made an entire playlist), as well as their live-in-your-head video for “Psycho Therapy.” I think about how Sylvia Plath, who, like all of us, was a product of her time. Re-reading The Bell Jar now makes me think about how it’s a case study in self-stigma and structural stigma. Terms we didn’t use then. We know more now.

Problematic depictions in the mass media won’t end – sensationalism and romanticization frequently propel narrative arcs – but the huge role that popular culture can play in the understanding and representation of mental health makes a book like Lifeline such a notable work in illustrating the story of living with and supporting someone with mental illness through ups and downs, contradictions, contours, and textures.

“Healing is not linear, darling,” the author writes—and the book’s format artfully follows that statement by jumping around in time as the author reflects and looks forward, trying to imagine a time when the person she cares for so deeply might be better.

Further reading: Breaking Stigmas, Saving Lives.

Fateema Sayani

Fateema Sayani has worked in social purpose organizations and newsrooms for twenty-plus years, managing teams, strategy, research, fundraising, communications, and policy. Her work has been published in magazines and newspapers across Canada, focusing on social issues, policy, pop culture, and the Canadian music scene. She was a longtime columnist at the Ottawa Citizen and a senior editor and writer at Ottawa Magazine. She has been a juror for the Polaris Music Prize and the East Coast Music Awards and volunteers with global music presenting organization Axé WorldFest and the Canadian Advocacy Network. She holds a bachelor’s degree in journalism, a master’s degree in philanthropy and nonprofit leadership, and certificates in French-language writing from McGill and public policy development from the Max Bell Foundation Public Policy Training Institute. She researches nonprofit news models to support the development of this work in Canada and to shift narratives about underrepresented communities. Her work in publishing earned her numerous accolades for social justice reporting, including multiple Canadian Online Publishing Awards and the Joan Gullen Award for Media Excellence.

Subscribe to Catalyst

Subscribe to get our magazine delivered right to your inbox

Related Articles

When you think of mental health, do you want to have a good laugh?

Humour is one of the most effective ways brands have to capture attention and be memorable. It’s not always easy, but if you can strike the right balance between tone and your target market’s funny bone, it’s gold.

Unfortunately, for most health brands, humour represents pitfalls. Fears of poor taste or making people feel minimized are real. This fear of funny means, for the most part, we are left tugging on heartstrings or seeking inspiration from the patient as brave soldier.

In fact, a few years ago, SickKids launched a brilliant campaign where they combined the two with children as gritty-eyed warriors fighting illness and injury. While there were critics of the VS Limits campaign, it did its job, surpassing the $1.5-billion goal.

When you are a mental health advocate, there is a lot on the line. With so much stigma associated with mental health, anything that might further confuse issues makes the use of humour thorny. Yet, if you are struggling with mental illness, you don’t always want to be immersed in the dark imagery that often accompanies stories of mental distress. Unfortunately, for a long time, mental health meant a series of images of people with their heads in their hands.

We contain multitudes

The reality is much more dynamic. Mental health discussions, even the toughest of them, can be about optimism, change, and recovery. We don’t have to go the warrior route. It is possible to go for and succeed with the holy grail of healthcare promotion: humour.

Ottawa Public Health has been a champion of that approach. When speaking to Kevin Parent, the social media lead, he noted that while the public health unit is often funny, they can get away with it because, first and foremost, they are always authentic. That means they express a variety of voices on their feed. Some are full of comedic relief; others are serious, sad, educational, and informative – essentially, the range of human emotions.

For example, during the pandemic, mask discussions lost all humour for me, and yet my inner sci-fi geek was tickled when they featured The Maskalorian with the quote, “This is the way.” It made a tiresome topic fresh and funny.

“We do everything we can to stay authentic,” Parent says. “If you understand your audience, if you take the time to know them, then you’ll know what they think is funny. You’ll also know when they need a laugh. It isn’t that a particular thing is right, and another is wrong; it’s more a case of what’s right – for right now.”

So, during the emergency phase of the pandemic, maybe mask-breath jokes were too soon – though, these days, most people would have experienced this and get the reference.

In recent years, constraints that have kept humour at bay in the health sector have fallen due to the popularity of social media influencers and the acknowledgement by health professionals that the voices of those with lived experiences are not only relevant but important in everything from research to recovery.

The shift in perspective was aptly demonstrated when that bastion of academic rigour, Harvard University, conducted best practice educational sessions with TikTok mental health influencers Rachel Havekost and Trey Tucker. The engagement brought better health information to the public through those popular feeds. However, it’s not always a successful partnership if the fit between knowledge and theatre isn’t right. No matter how well-intentioned or researched, if the content isn’t entertaining, it does not get viewed.

Some experts advise healthcare marketers entering the humour arena to be gentle. That’s not bad advice, but it does leave the content somewhat bland. When the Mental Health Commission of Canada decided to refresh a few years ago, it wanted to bring the brand into the light and occasionally tickle the funny bone. This meant banishing images that conjured deep unhappiness. You know them: a dark day and a sad person sitting alone on a bed, facing a corner. It’s usually in black and white to reinforce the glumness of the subject matter. If that wasn’t enough, there are also lots of clouds.

Silver linings

The change to optimistic imagery wasn’t simple. As many experts insisted, mental health isn’t always sunshine and daisies. The challenge is understanding what viewers are looking for so that good information can be digested.

I am not alone in saying nothing about dreary imagery draws me in and makes me want to learn, see, or hear more. If I also get served a lecture using technical language, I’m out. It’s not that dark and difficult times are never part of the mental health journey, but contributing to doom scrolling hardly seems progressive. Nor is it that viewers don’t want well-researched information, but anyone who has ever had a loss of mental health knows the process is not simple. There are good and bad times, sometimes in the same 24 hours. Regardless of where you are on the continuum, a little humour can go a long way. A good laugh can reduce stress and tension, provide relief from pain, improve your mood, and has a host of other well-documented impacts.

The issue is finding the right balance of information and entertainment. Infotainment is easy to say and hard to achieve. It’s fine to explain that laughter is the best medicine and cite a series of research studies, but putting humour into play while delivering information responsibly to an audience that often includes people at risk is difficult.

Mental health can be funny, but it can also be sad, scary, and complicated. For advocates, advertisers, and audiences, getting the balance right is not only essential, but it can also be life-altering.

Further reading: No more doom and gloom: How we’re using photography to inspire hope.

Resource: Fact Sheet: Common Mental Health Myths and Misconceptions.

Debra Yearwood

A communications pro with more than 20 years of executive experience in the health sector, expertly navigating everything from social marketing to crisis comms. When she’s not advising on the boards of Health Partners or Top Sixty Over Sixty, she’s busy finishing her book on thriving in later life (because why stop now?). Certified Health Executive by day, diversity advocate and magazine contributor by night—Debra’s the one you call when things need fixing or explaining.

Subscribe to Catalyst

Subscribe to get our magazine delivered right to your inbox

Related Articles

The sounds of sorrow and hope amid a tangle of words on injustice, racism, and brutality often define conscious rap music. Their presence is an acknowledgement of the challenges faced and a call to Black communities to stay strong despite the pressures of prejudice. Music’s role in expressing the internal, external, and seemingly eternal conflicts arising from oppression makes it an important player in the survival of Black culture, identity, and mental health.

Everyday racism activities that permeate daily life become ‘normalized’ in the mainstream despite stated commitments to equity. These transgressions often appear mindless or habitual and while they hurt, it’s sometimes easier to ignore than battle every incident. When I was a political assistant on Parliament Hill many years ago, small green buses would wind their way around the precinct, bringing staff and members to different buildings. Regularly, the buses would drive past me. The drivers would see me flagging them but never considered that a Black woman could be a Hill staffer, so they drove by. They passed by me so often that when they did stop, I was startled.

The loop

Freda Bizimana

Given their frequency, these racist moments are regularly treated as too minor to address. However, their cumulative impact reproduces social relations of power and oppression and, over time, damages the health and well-being of Black people and other people of colour. In effect, everyday racism creates systemic racism, and systemic racism creates the environments that allow everyday racism to thrive. They both produce challenges to mental health.

When violence against Black citizens is normalized or overlooked with little to no reaction from agencies such as the media or government, then it would be easy to allow despair or cynicism to take over. According to a 2018 study published in The Lancet, Black Americans report upwards of 14 poor mental health days for every reported police killing of an unarmed Black American in their state of residence.

There’s all sorts of trauma from drama that children see

Type of s–t that normally would call for therapy

But you know just how it go in our community

Keep that s–t inside it don’t matter how hard it be

– Lyrics, J. Cole, “Friends” 2018.

The impacts are multi-generational. Discrimination experienced by a parent may also negatively impact their child’s mental health, even if that child did not experience the discriminatory treatment firsthand. In the same Lancet study referenced above, the impacts of “indirect” or “vicarious” racism were found to worsen the progression of inflammatory disease, sleep disturbances, chronic health conditions, and cognitive function – all of which decay mental health.

Music has been and remains an important part of Black cultural expression. Its ability to communicate complex messages and emotions is integral to its construction. It was fear of the effectiveness that led U.S. legislators to ban slaves from using drums in 1739. Almost 150 years later, in 1988, NWA’s single, “F–k tha Police,” drew similar concerns from authorities when it was released.

It’s not surprising then that rap music and hip-hop culture play an important role in not just expressing the concerns, fears, opportunities, and hopes of contemporary Black people but also providing an outlet to improve mental health in those same communities. In 1998, researcher and clinician Dr. Edgar Tyson introduced hip-hop therapy at the 20th Annual Symposium of the Association for the Advancement of Social Work.

Mama had four kids, but she’s a lesbian

Had to pretend so long that she’s a thespian

Had to hide in the closet, so she medicate

Society shame and the pain was too much to take

– Lyrics, Jay-Z, “Smile,” 2017.

Hip-hop therapy is a fusion of hip-hop, bibliotherapy, and music therapy. Music therapy has established credentials that stretch back to research done by Zane Ragland and Maurice Apprey as early as 1974. Similarly, bibliotherapy, which focuses on the use of literature, such as stories and poetry, to facilitate treatment, is also well established and has been proven to be effective by several systematic reviews in the treatment of emotional, physical, and mental health problems among adults.

Tyson’s groundbreaking research is the cornerstone of contemporary hip-hop therapy and lends itself well to culturally appropriate care, particularly among young people.

Toronto therapist Freda Bizimana, MSW, RSW, works with Black and racialized youth in conflict with the law at The Growth & Wellness Therapy Centre. She shared how challenging it is to reach Black youth, particularly those who have come to therapy because of their interaction with the justice system. “They don’t want to be there talking to a stranger,” she says. “Hip-hop gives us a bridge, a way to connect through something they love. It’s a modality that is not rooted in European experience. It brings back the drums common to the African Black diaspora.”

New release

In her practice, Bizimana notes that clients are not often engaged and start with one-word answers. She’ll look at their headphones and ask them what they are listening to. They’ll share their favourite songs, then delve into lyrics. At some point, Bizimana will ask them, ‘Do you ever feel that way?’ Suddenly, they are having a conversation. “This modality eases them into the process,” she says.

How does Bizimana respond to critics who question the efficacy or appropriateness of this therapeutic approach? “Hip hop is a mirror of society. If you have a problem with it, you need to look at what’s happening in society,” she says. “How are we addressing anti-Black racism? What is happening within our school systems with Black youth? What are we doing to deal with police brutality? Why are young people numbing themselves?”

No need to lie into your emerald soul

You surely know gold is always in your throat

Why not let it shine?

You’re in control of the dream

– Lyrics, Kid Cudi, “The Commander,” 2016.

Rap can surf off strife and act as a vehicle of escape. Political commentary set to a 4/4 beat transforms frustration with structural racism into an accessible anthem of collective experience. Kendrick Lemar’s album, To Pimp a Butterfly, provides political commentary on faith, culture, and race. The song “Alright” pulled those insights together and made its way onto Pitchfork and Billboard best-of lists for 2015. Lamar notes in the poem that runs before and after the song that the conflict is based on discrimination and apartheid. Like the songs of slaves, he sings that with God, things will be alright. The widescale popularity and uplifting beat eventually led to its adoption by the Black Lives Matter movement, reinforcing the relationship between conscious rap and activism.

Collective efforts

Rap’s themes of overcoming obstacles and surviving life’s challenges are specific as well as inspirational. They reflect the realities of daily life for many in Black communities. Hip-hop therapy takes rap music and other elements of hip-hop culture and blends them to create a culturally relevant therapeutic offering. Unlike regular music therapy, it also embraces group therapy. This allows for shared experiences and reduces the feelings of isolation that are often the consequence of racism. The evidence shows that it can reduce depression and anxiety while also improving communication and emotional expression.

Hip-hop therapy also does something else; it empowers. Rap music varies widely and can reinforce doctrines of sexism, commercialism, and drug culture. For Black women, it can be another source of disrespect and denial. Through hip-hop therapy, women can counteract those influences through the creation of lyrics and discussions that tell their stories in their voices.

“Hip hop gives a voice to Black youth,” Bizimana says. “It allows them to have a space to express, heal, and grow with a medium that is familiar. I’d like to see it used more frequently in Canada,” she says, noting that more therapists are adopting this approach through individual and group sessions. She is seeing schools incorporating it into curricula. “Sometimes help can come in the form of a coping playlist,” she says, “like a playlist for when you are sad and another for when you need motivation.”

Years ago, if asked, I would have expressed my disdain for hip-hop culture. It often struck me as self-flagellation, and I could not see why so many young Black people, particularly women, were enamoured with it. However, when my son began to play conscious rap for me, and I listened to lyrics that reflected my own truths, I could not help but rethink my opinions. Now, in moments of doubt and struggle, when cultural norms have stifled my options or limited my view, I find the music uplifting. No small wonder I would be caught by the appeal of hip-hop therapy. It captures and formalizes what many of us in the Black community already know: music heals, and no music heals as well as our own.

Further Reading: Weaving Through the Challenges

Resource: Experiences with Suicide: African, Caribbean, and Black Communities in Canada

Debra Yearwood

A communications pro with more than 20 years of executive experience in the health sector, expertly navigating everything from social marketing to crisis comms. When she’s not advising on the boards of Health Partners or Top Sixty Over Sixty, she’s busy finishing her book on thriving in later life (because why stop now?). Certified Health Executive by day, diversity advocate and magazine contributor by night—Debra’s the one you call when things need fixing or explaining.

Illustrator: Holly Craib

Holly Craib explores the relationships between colour and light in her artwork. She won a 2023 Applied Arts award for a conceptual illustration series.

Related Articles

Ahead of the International Trans Day of Visibility – an annual event dedicated to supporting trans people and raising awareness of discrimination — the Stigma Crusher reflects on ways of showing up and showing support.

It’s easy to be a friend, a comforter, a confidant, a ramen pal, or a late-night horror flick ride-or-die – but that is not what it means to be an ally. So, how does one be an ally? And more to the point, how does one be a good ally to transgender and nonbinary communities in a political and social climate that can be downright hostile and dangerous?

An ally is a person, often cisgender (a person whose gender corresponds to the sex assigned at birth), who supports and/or advocates for transgender and non-binary people. It can seem daunting to be an ally with all the hate in the world – sometimes, I think I would rather hide until everything feels just a little safer – but for those I love, I can’t. Besides, there are simple actions we can take to be a better ally, right now.

It starts with education

There are 100,815 transgender and non-binary persons in Canada, according to Statistics Canada. That’s 1 in 300 Canadians. Gender refers to an individual’s personal and social identity. Transgender refers to people whose gender does not correspond to their sex assigned at birth (based on a person’s reproductive system and other physical characteristics). Non-binary refers to people who are not exclusively a man or a woman. In both cases, the gender identity, which is the experience of gender internally, does not match what society expects.

Maybe, as an ally, you are familiar with these terms, but do you know about the history of trans and non-binary rights in this country? Have you read any trans or non-binary-authored resources lately? Being a good ally is more than being a friend; it is important for us to educate ourselves about the lived experiences of trans and non-binary people to better understand what they encounter daily. And we have to educate ourselves. It is critical to consider where we put the burden of this work.

Names and pronouns

For many transgender and non-binary people, names and pronouns are an important issue. They may find themselves constantly on the receiving end of being called by their old (“dead”) name or the wrong gender or pronoun (“misgendered”), which can be incredibly hurtful. The most respectful approach is to introduce oneself using one’s preferred name and pronouns and ask if you’re not sure. Mess up? Respectfully apologize, then concentrate on correcting yourself moving forward.

Safety

Allyship is incredibly important in keeping transgender and non-binary people safe – especially in today’s politically charged climate. And it can start young. Mae Ajayi, who is non-binary and a parent, says making allies of our kids is one of the best ways to keep trans and non-binary kids safe.

“It’s about having conversations with kids that are really explicit about transphobia,” Ajayi says. Explaining what it is and how to be an ally is a helpful start, says Rachel Malone, parent of bigender Sacha, and cisgender Peter. “We can’t wrap our kids up in bubble wrap, right? And we can’t be there 100 percent of the time, so we can’t be their only protectors.” Malone knows there is a lot to do to improve safety for transgender and nonbinary people. She told me how Sacha’s brutal bullying over her gender identity in kindergarten resulted in serious mental health concerns and asked me not to use her or her children’s real names because of reports of families of transgender kids being targeted with violence.

Safety is a theme not only for children but also for transgender and non-binary adults, who are more likely than cisgender adults to experience violence. Allies who stand up for their transgender and non-binary friends, colleagues and neighbours are crucial to improving safety for these adults.

Mental health

Robyn Letson, MSW, RSW, is a trans social worker and psychotherapist who works with transgender and non-binary clients. According to them, “There is huge potential for allyship in providing affirming mental health care to trans and non-binary people.”

Transgender and non-binary individuals are more likely than cis-gender individuals to live with poor mental health. This could be due to a variety of reasons, but the transphobia, prejudice, and discrimination that they experience just for existing certainly does not help.

An ally can help support the mental of transgender and non-binary people by being supportive, respecting their privacy by not asking invasive medical questions about transition or hormones, and seeking their feedback on how you can adjust your care approach (you may not know that your approach isn’t working unless you ask). You can signal with signage that workplaces, schools, and clinics are safe and affirming spaces for transgender and nonbinary people.

It also takes work to really help support the transgender and non-binary folks in your life. “I would suggest starting with critical self-reflection,” says Letson. “For cis people who want to begin or deepen a journey of practicing better allyship and solidarity with trans people, I always suggest beginning with one’s own relationship to gender.”

Ongoing commitment

There is no “completed” badge for being an ally – it is all about continuous education, working against discrimination and transphobia, and challenging one’s own biases.

“Make space for fewer assumptions and just allow yourself to feel like you don’t know,” suggests Mae Ajayi. “Cis(gendered) folks should understand how sad and scared people are right now and that it feels very frightening as a trans person and also as a parent – it’s a very real danger,” they say.

I can only imagine how frightening it is to be a transgendered or non-binary person in Canada right now, and as an ally, that makes my blood boil. However, being angry isn’t enough – being cisgender is currently a privilege in our society, and it is an ally’s responsibility to use that privilege to act.

It sounds like a big job, but if you start with supporting transgender and non-binary people, work on educating yourself, commit to learning and using the correct names and pronouns, think about protecting their safety, support their mental health, and then make an ongoing commitment to act against transphobia and discrimination, you will be well on your way to being a better ally.

Jessica Ward-King

BSc, PhD, aka the StigmaCrusher, is a mental health advocate and keynote speaker with a rare blend of academic expertise and lived experience. Equipped with a doctorate in experimental psychology and firsthand knowledge of bipolar disorder, she’s both heavily educated and, as she likes to say, heavily medicated. Crazy smart, she’s been crushing mental health stigma since 2010.

Related Articles

Top reads worth revisiting from the Mental Health Commission of Canada’s magazine

With the tagline “Conversations on Mental Health,” we have a wide berth when considering story ideas for The Catalyst. This is by design. Part of the Mental Health Commission of Canada’s work is to reduce stigma, and that starts by making space for discussions about lived realities, challenges, news, and ideas. We compiled a summary of stories published in 2023 that reflect that ethos to start off your New Year. Happy reading.

Is there an elephant in the room?

Stories develop in myriad ways. The piece “How to Break Up With Your Therapist” emerged from side conversations with friends and colleagues, seemingly unable to speak above a whisper about how it wasn’t working out. When I responded by proposing a piece on the delicate art of saying, “It’s not you, it’s me (or vice-versa),” I kept hearing how useful this would be. We commissioned author Moira Farr to tackle the issue in July 2023. Later that year, in October 2023, The New York Times published a piece on the same topic with a similar headline and sub-headline. We were flattered.

On the subject of things we don’t talk about enough, in March, writer Debra Yearwood wrote about the cringier aspects of a bad funeral (mispronouncing the name of the deceased – egad!) and how different aspects of saying goodbye can support bereavement processes. The delightfully cheeky illustration nails the premise of the article and invites readers into the story.

Serious about series

A collection of linked stories allows us to explore an issue in depth across multiple weeks. We plan these out in advance to permit research, reflection, and writing and to assure stories are up to date with current and emerging information. In November, we published four stories within the theme of Money & Mental Health for Financial Literacy Month. It covers mindsets, housing, economic literacy and empowerment, and the cost of therapy.

Meanwhile, our annual literary series Mental Health for the Holidays embraces some of the tarnish on all the sparkle of the season. We dive into complicated family dynamics with stories of overcoming the more trying aspects of the holidays not always seen in those commercial depictions. The pieces are true tales told with hope and humour.

Lived experiences

The level of detail and nuance that emerges from a personal tale can shed light on a topic profoundly. That was the case with Jessica Ruano’s story about her partner’s suicide. Meanwhile, Florence K – musician, mother, CBC host, and doctoral candidate – took the theme of this year’s Mental Health Week – #MyStory – and shared her personal story of mental health challenges, wellness, and discovery.

On language

When working to reduce stigma, it’s about the stories we tell – and how we tell them. Part of our internal annual review of our style guide looks at language choices. We decided to provide context around these choices in a series called Language Matters. In this way, we can share our rationale outside the organization with the hopes that word will spread. For example, how to phrase language around suicide or the use of drugs, alcohol, or other substances.

Worth revisiting

The following stories – two from our annual literary series Mental Health for the Holidays – all received nominations for the Canadian Online Publishing Awards. Winners are announced in February. In the best column category are Dave Bidini’s piece, Getting Outside to Get Into Your Head and Moira Farr’s essay May Your Days Be Merry and Bright – As Possible, both from 2022. Debra Yearwood’s piece, Putting the Men in Mental Health, received a nod in the Best Service Article category, while The Dread in Your Head – about eco-anxiety – received a nomination for Best Lifestyle Article.

Fateema Sayani

Fateema Sayani has worked in social purpose organizations and newsrooms for twenty-plus years, managing teams, strategy, research, fundraising, communications, and policy. Her work has been published in magazines and newspapers across Canada, focusing on social issues, policy, pop culture, and the Canadian music scene. She was a longtime columnist at the Ottawa Citizen and a senior editor and writer at Ottawa Magazine. She has been a juror for the Polaris Music Prize and the East Coast Music Awards and volunteers with global music presenting organization Axé WorldFest and the Canadian Advocacy Network. She holds a bachelor’s degree in journalism, a master’s degree in philanthropy and nonprofit leadership, and certificates in French-language writing from McGill and public policy development from the Max Bell Foundation Public Policy Training Institute. She researches nonprofit news models to support the development of this work in Canada and to shift narratives about underrepresented communities. Her work in publishing earned her numerous accolades for social justice reporting, including multiple Canadian Online Publishing Awards and the Joan Gullen Award for Media Excellence.

Related Articles

Our annual literary series touches on the complexities of the season.

Our tagline for The Catalyst is “Conversations on mental health.” This idea is meant as shorthand for our magazine’s purpose and a signal to our readers that the door is open to discuss mental health.

This welcome mat also speaks to the larger mission at the Mental Health Commission of Canada (MHCC) to reduce stigma. When we speak openly about challenges, illnesses, problems, and wellness, we recognize that mental health is part of our overall health. Such conversations can be a gateway to meaningful change, and the holiday season feels like an especially good time to tackle the complexities and multitudes of our mental health.

So every December, we run our Mental Health for the Holidays series to touch on the things not seen in those sparkly commercials. The goal is to normalize some of the challenges the holidays can bring and give readers a sense of hope with a touch of humour.

Each year has a subtheme. In 2023, it was Moping, Hoping, and Coping. For 2024, we’re going with Good Tidings, Bad Partings, and New Traditions. While pithy and catchy, our hope is that they also speak to a trajectory of hope and promise through real voices and real stories.

I launched the series in 2022, some months after joining the MHCC as the manager of content and strategic communications. The Catalyst is one part of my portfolio and among the most visible parts of our work at the commission, whose other initiatives include research reports, public engagement, and knowledge translation projects such as guides, tools, courses, and webinars. The Catalyst is designed to be conversational, accessible, and even chatty while covering a gamut of issues, ideas, and research within mental health. It’s a little bit of Psychology Today with a dash of the New Yorker and a good dose of neighbourly advice.

The “recipe” for this annual series is to find stories that bridge the gaps between expectations and realities. It’s people taking their lumps and making honey lemon tea out of lemons, with a side of tin box cookies. They’re narratives about people facing challenges, told without tropes or platitudes.

Finding your way

Authors usually share a personal tale tied to a theme. For example, in 2022, Rheostatics rock band member and West End Phoenix newspaper publisher Dave Bidini wrote about skating, the germination of his memoirs, nostalgia, rinks, and rituals with richly beautiful detail and a certain musicality.

I was grateful that skating had delivered this creative idea to me at the expense of having to relive the stress, pain, and anger that came with reconstructing those times. I’d tried to make art through a discovery of this nostalgia. But nostalgia often uncovers the raw truths of the past while celebrating the best parts of being young and simple and new to the world.

Read Getting Outside to Get Into Your Head here.

Writer-instructor Moira Farr wrote with a witty self-awareness about navigating the holidays with a mood disorder and aging parents while highlighting the value of small talk.

Comfort and joy don’t just happen. You have to create them, and that requires generosity of spirit (as Scrooge famously learned) instead of going so far inward you can’t see beyond your own navel.

Read May Your Days Be Merry and Bright As Possible here.

Author Debra Yearwood grappled with her complicated relationship with Kwanzaa as she tried to unknot — like so many strands of tree lights — questions of identity and the commercialization of Christmas. Her rhythmic writing rollicks with insights as she wrestles with the emotional toll of holiday traditions and expectations.

Then comes the guilt. I ate way too much. All that butter and sugar. Ugh. I think I can hear my arteries hardening. The familiar commitments to do better follow. Tomorrow I’ll have a salad. . . but then someone invited me out for lunch. Dinner with friends is on for the next day and of course all those friends I haven’t seen in, like, forever. Drinks! Wasn’t that a special bottle of rum! Oh, and the best Côtes du Rhône I’ve had in an age. Recriminations arrive in the morning, delivered in that scathing voice I reserve just for me. Ugh, again! But the see-saw of pleasure and punishment is just getting started.

Read Sugar and Spice and Trying to Be Nice here.

This year

Writer Eleanor Sage tackles a timely subject in “Sister Acts,” where she details her efforts to bring a sibling out of a misinformation rabbit hole in order to recapture some sort of relationship while grieving the connection they once had. Watch for it in our December issue.

Putting this series together feels like a gift and an honour. It’s a delight to coach emerging and established writers, and work with an extraordinary team of authors, editors, digital and web experts, project managers, translators, and illustrators. I hope you enjoy it as much as we enjoy presenting it. Happy holidays.

Fateema Sayani

Fateema Sayani has worked in social purpose organizations and newsrooms for twenty-plus years, managing teams, strategy, research, fundraising, communications, and policy. Her work has been published in magazines and newspapers across Canada, focusing on social issues, policy, pop culture, and the Canadian music scene. She was a longtime columnist at the Ottawa Citizen and a senior editor and writer at Ottawa Magazine. She has been a juror for the Polaris Music Prize and the East Coast Music Awards and volunteers with global music presenting organization Axé WorldFest and the Canadian Advocacy Network. She holds a bachelor’s degree in journalism, a master’s degree in philanthropy and nonprofit leadership, and certificates in French-language writing from McGill and public policy development from the Max Bell Foundation Public Policy Training Institute. She researches nonprofit news models to support the development of this work in Canada and to shift narratives about underrepresented communities. Her work in publishing earned her numerous accolades for social justice reporting, including multiple Canadian Online Publishing Awards and the Joan Gullen Award for Media Excellence.

Related Articles

Butter just cost me $8. And I live in a major urban centre – I don’t even live in a rural or remote area of our vast country where I am sure that butter costs exorbitantly more. And you know what else just cost me more money? My medication, therapy (if I can even afford that at all), gas to get to the doctor to start with, pretty much every form of self-care – everything costs money, and everything costs more and more of it these days.

My financial health is taking a big hit in this economy, and I find myself lying awake at night worrying about my debt and bills and how I am going to make ends meet. And I worry about how I am going to take care of our health, for myself and my family – and, of course, our mental health. I don’t want to let mental health priorities slide, but if it comes down to paying for my son’s biweekly therapy bill or more material needs, what is going to take priority? And, of course, I’m never going to breathe a word of any of this to friends or family because stigma about mental health is one thing, but stigma about finances gives it a run for its money (no pun intended).

It is not an easy equation to balance, especially in a world that values physical health over mental health. Think of people who are living unhoused with substance use and mental health concerns. These are folks who are living with food insecurity, lack of shelter, and lack of safety. And they may also live with serious mental health needs. Trying to address only one of these concerns at a time is problematic because they all intersect, and you cannot manage the physical needs without addressing the mental and vice versa.

When I think of my son, I know that his mental health is just as important as his getting good nutrition. He cannot thrive without either his physical or mental health. But there is a difference between thriving and surviving, and in the current economy, sometimes the best we can hope for is to survive another day with the hopes of thriving when times are a little more favourable. When butter costs a little less, and we can afford medication and therapy and gas and self-care again.

If you’re lying awake at night wondering how you’re going to make ends meet, here are a few pieces of advice for your mental health:

- Breathe. It works for regular anxiety and money anxiety, too: deep breathing. Try looking up “four square breathing.”

- Do the math – on the actual state of your finances, that is. It may seem scary, but it helps you get a sense of control over what you are dealing with. And a sense of control is good when fighting anxiety.

- Reach out for help. Psychological help for your anxiety (money anxiety is real, and even one session at a free walk-in or a sliding scale counsellor can help!) and money help too. Just getting some help making a realistic budget from a nonprofit credit counsellor can help put you in the driver’s seat. You are never alone.

I would never recommend just surviving (rather than thriving) mental health-wise, but the balance is delicate, and I would be a fool to suggest otherwise. So, until everyone has access to affordable mental health care, take care of yourself the best you can and do what is right for you and your family. And do go easy on the butter until all this passes, will you?

Author: Jessica Ward-King

BSc, PhD, aka the StigmaCrusher, is a mental health advocate and keynote speaker with a rare blend of academic expertise and lived experience. Equipped with a doctorate in experimental psychology and firsthand knowledge of bipolar disorder, she’s both heavily educated and, as she likes to say, heavily medicated. Crazy smart, she’s been crushing mental health stigma since 2010.

Related Articles

The easy-to-remember three-digit number for suicide crises means that people in need of immediate support can call or text for help.

In early November, American actor Mark Duplass wrote about his mental health challenges on Instagram, including hosting a live space to discuss his strategies for coping, a part of which involves “a temporary denial of some of the heavy darkness so that I can focus on the light.”

Duplass, who has appeared in The Morning Show and The Mindy Project, encourages followers to phone the 988 any-time call and messaging service, which began in the U.S. in July 2022. As posts, mentions, articles, and conversations increase, there’s hope that those three digits will become common knowledge like 911.

Canada’s 988 suicide crisis helpline, which launched on November 30, means that people across the country can receive support via phone or text 24 hours a day. Callers will receive bilingual, trauma-informed culturally appropriate support from trained responders. While the service is designed to respond to those at risk of suicide, no one will be turned away. Those seeking to access other mental health supports, may be directed to other services in their area, for example.

“This will save lives,” says Michel Rodrigue, president and CEO of the Mental Health Commission of Canada (MHCC). “The 988 service is a vital support and more than just a number — a simple call in a time of crisis can be a turning point. This helpline breaks the silence and offers support to individuals.”

How it works

After texting or dialing 988, callers will receive a brief message to confirm that they have reached the right number. They will then be asked a few basic questions — for example, if they’d like to speak to someone in English or French — after which they’ll be connected with a trained responder in their community who will listen and provide support.

Calls or texts to 988 are confidential. No personally identifiable information will be disclosed or shared outside the 988 network, except as required or permitted by law, or when emergency intervention is needed to support the safety and well-being of the caller or texter, and/or the safety of others. The service is based on collaborative, person-centred approaches that use the least intrusive interventions to increase safety.

The service was established by the federal government and delivered by the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH). When people call 988, they’ll be supported by a decentralized, community-based service delivered through 39 partner centres and agencies across the country. These include distress centres and crisis lines, national agencies like Kids Help Phone and the Hope for Wellness Helpline, and local organizations such as South Asian Canadians Health and Social Services, an Ontario-based non-profit in Brampton.

The Distress Centre of Ottawa and Region, one of the centres in the 988 helpline network, takes calls from 613 and 343 area codes. Its responders are trained via the internationally recognized, certified suicide prevention model Applied Suicide Intervention Skills Training — also known as ASIST.

Its responders take ASIST as part of their 60-hour training, which covers everything from the phone system to active listening to crisis intervention. Kathyrn Leroux, the centre’s manager of media, marketing, and communications, has also taken the training.

She notes that having responders nearby enables 988 organizations to draw on local knowledge when callers need other social or emergency services. In cases where a centre is receiving a “rollover” call — that is, from another community or city when the local lines are at capacity — responders rely on services like 211 – a publicly accessible database of community supports – for referrals. Having these designated rollover services helps to avoid long wait times. Where there is a wait time, callers will receive a message encouraging them to stay on the line or the text thread.

Learning from the U.S.

Concerns about capacity have been part of studies about Canada’s 988 rollout, including those the MHCC raised in a 2021 policy brief. Planners of the 988 launch were able to gain insights on this topic based on experiences in the U.S. and the Netherlands (where the number is 113) ahead of implementation.

Since July 2022, the U.S. has invested nearly $1 billion in the service and has responded to nearly five million contacts. In the first year, it has been able to decrease its average response time from 2 minutes 39 seconds to 41 seconds. Its 988 number is supported by more than 200 local and state-run call centres, and over time has expanded to add text and chat services in Spanish along with specialized services for 2SLGBTQI+ youth. Future developments include video phone access to better serve deaf and hard-of-hearing individuals. As the service ramps up, more public campaigns may be on the horizon. A recent USA Today story showed that a year after its implementation, awareness rates (13%) still have a ways to go.

Even with the insights from other countries, Canada’s launch and maintenance of 988 is a complex task. Alongside the country’s vastness, diversity, and principles of inclusion, it needs to deal with technical considerations. To give just one example, the Canadian Radio and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) had to transition to 10-digit dialing in Newfoundland and Labrador, northern Ontario, and Yellowknife before they could get the 988 number up and running.

People in Canada will start to see information across social media between now and February as the service launches and service providers acclimate. So far, the federal government has allotted $156 million over three years for the service.

As it rolls out, 988 providers will be tracking the number of contacts (calls and texts), wait times, and the abandonment rate – when a caller or texter ends the contact before connecting with a responder – with a view to improving service times.

Say it early, say it often

The phrase “say it early, say it often” serves as shorthand, both for responders and for anyone involved in conversations about suicide. Why? Because it emphasizes an open, straightforward, and non-judgmental dialogue that is at the heart of training initiatives.

“Conversation is important,” Leroux says. “We want to get away from ‘Are you thinking about hurting yourself?’ and ask more straightforward questions such as ‘Are you thinking of suicide?’ and then ‘Have you done anything to harm yourself today?’ Doing that really allows you to focus in and helps people open up. It demonstrates that you are willing to talk about it and talk about it in a straightforward way. It allows you to determine where they are and get people the help they need.”

Distress Centre responders are also trained in crisis de-escalation that uses a range of questions to assist with identifying the scale of the issue and the next steps. No matter the call, the goal is the same, Leroux says: to get people to safety or to a safety plan.

The scale of the issue

Suicide remains a significant public health concern in Canada, affecting individuals of all ages, genders, and backgrounds. It also disproportionately affects certain populations, including girls, men and boys, people serving federal sentences, survivors of suicide loss and suicide attempts, 2SLGBTQI+ groups, and some First Nations, Métis, and Inuit communities.

According to Statistics Canada, about 4,500 people in our country die by suicide every year, which is around 12 people a day. And for every person lost to suicide, many more experience suicidal ideation or attempts.

The reasons for suicide are complex: they include biological, psychological, social, cultural, spiritual, economic, and other factors. According to a leading researcher in the field, the people who think about and attempt suicide are seeking an end to deep and intense psychological pain.

When it comes to preventing suicide, how we talk about it matters. Safe, factual, and responsible portrayals and messaging can have a positive impact. When discussing suicide, it’s also important to include any preventive actions taken, convey narratives that demonstrate hope and resilience about recovery, and mention the resources available for help and support.

Societal shifts

And as we learn more about suicide, the conversation is shifting. The Senate standing committee on social affairs, science, and technology’s recent update to the federal framework for suicide prevention included recommendations to:

- recognize the impact of substance use on suicide prevention

- fund research into interventions

- create a nationwide database to better collect national data related to suicides, attempts, and effective prevention measures

- replace the concepts of “hope and resilience” with “meaning and connectedness.”

This shift in language also resonates with other perspectives; for example, the terms life promotion and wellness, which many Indigenous communities use when discussing suicide prevention. The First Nations Mental Wellness Continuum Framework — developed by the Thunderbird Partnership Foundation with Indigenous and non-Indigenous partners — identifies hope, meaning, belonging, and purpose as underpinning many Indigenous ways of knowing. As the framework explains, aligning these four aspects in a person’s everyday life brings that person a feeling of wholeness that protects them and acts as a buffer against mental health risks and potential suicidal behaviours.

Moira Farr has also noticed a change in the conversation since After Daniel: A Suicide Survivor’s Tale was published in 1999 — a book that delves into the death of her partner. Farr is a journalist and an instructor who researches and writes on a variety of topics for international and national publications.

“I would say there has definitely been a shift in people’s willingness to openly discuss mental health issues, including suicide, in the past 20 years,” she says. “The campaigns to raise awareness about how and where to get help and to get people talking more honestly about their own mental health struggles seem to me to have been a positive force.”

By promoting understanding and empathy, we can create an environment where people feel safe and comfortable discussing their mental health challenges. This includes recognizing that seeking help is a sign of strength — not weakness — and that mental health is just as important as physical health.

“The new helpline underlines the reality and importance of suicide prevention,” Rodrigue says. “It speaks to the fact that suicide is a significant public health issue that affects people of all ages and backgrounds — and can be prevented. This is a collective effort that will help to reach more people in Canada to support their well-being.”

Fateema Sayani is the manager of content & strategic communications at the Mental Health Commission of Canada.

Tools and resources

- If you are thinking about suicide, or worried about someone else thinking about suicide, call or text 988 for suicide prevention support, any time of day or night.

- The Hope for Wellness Helpline continues to provide immediate non-judgmental, culturally competent, trauma-informed emotional support, crisis intervention, or referrals to community-based services for Indigenous Peoples. You can reach Hope for Wellness by calling 1-855-242-3310.

- Children and young adults in Canada in need of mental health support and crisis services can continue to contact Kids Help Phone by calling 1-800-668-6868 or texting CONNECT to 686868 from anywhere in Canada, at any time.

- Non-crisis support. Tip sheet: Where to Get Care — A Guide to Navigating Public and Private Mental Health Services in Canada.

- Resources: Suicide Prevention (MHCC)

- Postvention Resources: Postvention activities are crucial for helping those affected by suicide (e.g., those bereaved after suicide loss) and for reducing the risk of further suicides or crises.

- Further reading: Surviving Suicide Loss.

Fateema Sayani

Fateema Sayani has worked in social purpose organizations and newsrooms for twenty-plus years, managing teams, strategy, research, fundraising, communications, and policy. Her work has been published in magazines and newspapers across Canada, focusing on social issues, policy, pop culture, and the Canadian music scene. She was a longtime columnist at the Ottawa Citizen and a senior editor and writer at Ottawa Magazine. She has been a juror for the Polaris Music Prize and the East Coast Music Awards and volunteers with global music presenting organization Axé WorldFest and the Canadian Advocacy Network. She holds a bachelor’s degree in journalism, a master’s degree in philanthropy and nonprofit leadership, and certificates in French-language writing from McGill and public policy development from the Max Bell Foundation Public Policy Training Institute. She researches nonprofit news models to support the development of this work in Canada and to shift narratives about underrepresented communities. Her work in publishing earned her numerous accolades for social justice reporting, including multiple Canadian Online Publishing Awards and the Joan Gullen Award for Media Excellence.

Subscribe to Catalyst

Subscribe to get our magazine delivered right to your inbox

Related Articles

In this fourth and final piece in the series, we explore the costs of therapy and the financial decisions people make when seeking help.

When Affordable Therapy Network founder Katie McCowan was in her final year of therapist training, she started experiencing mental health challenges and decided to seek therapy.

“I was in school, working as a waitress, not making a lot of money. So I found myself Googling ‘affordable therapy options Ontario,’” she says, referring to her inspiration for launching the Canada-wide online database in 2015. To meet her needs, she used one option (provided by her school) at $40 per session and also tried a private therapist at $140. But while the private sessions were helpful, they cost her a day’s wages. “$40 was affordable, but I wasn’t able to choose my therapist, and therapeutic fit is very important.”

McCowan realized that this was a common challenge and thought, “What if I built a website and listed therapists who offer lower rates so people can connect with them?” She began with her esteemed colleagues, since new graduates often charge less. Word spread. The network grew. And during the pandemic, demand exploded.

The website now lists more than 550 vetted therapists, all with sliding-scale fee options and about half offering subsidized spots at $65 or less (including some pay-what-you-can and pro bono options). “A wide variety of therapists list with us, and most offer a certain number of low-cost spots, maybe five or so, that are subsidized.”

While these lower-cost rates tend to be less than half the price of private therapy, considering today’s socio-economic realities, “I know that’s a stretch for a lot of people,” she says. Still, McCowan acknowledges that fees in the private industry are fair and appropriate. “Therapists don’t charge more than they should. There is extensive training, extensive supervision, and it’s quite challenging work.”

Financial insecurity and therapy

If you feel that life seems more expensive lately, you’re right. According to the Canadian Social Survey on quality of life and cost of living, the consumer price index rose 6.8 per cent in 2022 — the biggest jump in forty years — with costs for food (up 8.9 per cent), shelter (up 6.9 per cent), and transportation (up 10.6 per cent) increasing the most.

Such pressures have had a mental health impact on many people. Half of our population has been affected by “inflation, the economy and financial insecurity,” according to a post-pandemic survey from Mental Health Research Canada (MHRC), and are “showing signs of worsening mental health.” In fact, since the previous year’s poll, this group reported “higher self-rated anxiety (33%) and depression (32%), higher suicide ideation (31%) and alcohol (23%) or cannabis dependency (22%),” among other issues.

Indeed, not only can financial stress impact mental health, it can affect decisions about therapy and other mental health resources. In Canada, psychotherapy and psychology services may be covered (in part or completely) by private health insurance, such as insurance plans provided by an employer, or purchased directly by an individual. Mental health service providers offer more specialized care, which ranges depending on the severity of the issue. Certain services need a doctor’s referral, while some are self-directed and available online or by phone or text message. Others are public (funded by governments) or provided by charities, community groups, and other organizations. The Canadian Mental Health Association, for example, has branch offices to direct people to support, including free counselling provided in some of its 70 regions in 330 communities across Canada.

CMHA programs are “culturally safe and meaningful,” which is significant when looking at the impact of financial insecurity on mental health and access to supports, including therapy, for various populations. To cite just one example, the MHRC survey found that racialized persons, people from 2SLGBTQI+ communities, young adults (ages 18 to 34), students, and those who are unemployed, have low incomes, or are in financial trouble are more likely to report high levels of anxiety.

Fee scales to improve access

To help clients get access to mental health services, the Calgary Counselling Centre has had a sliding fee scale since it opened in 1962, says CEO Robbie Babins-Wagner, who is also an adjunct professor and special instructor at the University of Calgary.

“We have to make sure we meet the needs of vulnerable people, including those vulnerable financially because of health issues, mental health problems, or other social issues,” says Dr. Babins-Wagner, whose passion is “clinical practice and making sure clients get the results they deserve.” Babins-Wagner and her team employ scientific, data-driven research methods and tools, including “session-by-session” outcome measurement (with questionnaire tools in 24 languages) and financial modelling. “We use that data to try and understand how we’re helping people and improve what we’re doing.”

The centre assigns new clients to a counsellor “no later than noon the next day” after receiving a request and uses no formal means testing. “We ask a client what their income is, and we trust them,” she explains. “When a client says they can’t afford the suggested fee, we say, ‘Your counsellor will discuss that with you; the fees are not a barrier to service.’ The counsellor has the discretion to bring it down to, generally, as low as $8 an hour, but if necessary, we’ll bring it lower. We truly don’t want fees to be a barrier.”

The centre collects this data, Babins-Wagner says, “because we want to understand what’s happening for clients and where the pain points are.” Through an internal process using blind data, every time there’s a fee change, we “look at what the suggested fee was, what the client could afford. Then we put that in our database and run that data to see whether clients from certain income groups are struggling more than others and if we need to make changes. Those are the kind of changes we typically make to the fee scale, and we test it to see if it’s achieving the intended benefit, which is meeting client needs.”

With the economic challenges Calgary has endured since late 2014, she says the centre now reviews its fee scale every year or two instead of every five years “because we know we can’t wait, and people are being more impacted than we’ve seen historically. So, we use data and current conditions to look at these factors.”

Finding a way

Dr. Elana Bloom, psychologist and director of campus wellness and support services at Concordia University agrees that “navigating mental health resources can be challenging.” While her expertise isn’t related to affordability per se, she understands the issue based on her clinical practice and is familiar with the mental health resources in her province, particularly for the student population.

“In Quebec, individuals (including young adults) can access mental health and psychosocial services, including psychotherapy and crisis supports, at CIUSSSs” [integrated university health and social service centres and community-based organizations]. At Concordia, we offer an array of mental health services, including wellness programming and psychotherapy with counsellors and psychotherapists. If you’re not able to access services or resources in a timely manner, if there’s a wait-list, another option is to seek services privately.”

Dr. Bloom advocates an “expansive view of wellness and well-being” — where seeing a therapist may be part of a broader wellness strategy that can include self-care, social interactions, physical well-being — and “leveraging technology” to make the most of self-directed mental health tools and resources. “Being a psychologist myself, I believe in the positive impact of psychology and in seeing a therapist,” she says. “But I also think mental health is more than just meeting with a psychologist; it’s important to take care of our own mental health and well-being using many different resiliency-based strategies beyond going to see a psychologist or therapist.”

She also notes that services are available to meet the particular needs of specific populations, such as Indigenous, 2SLGBTQI+, and African, Caribbean, and Black individuals.

Therapy 2.0?

While young people (and the rest of us) are increasingly living their lives online — and this extends to therapy — not all mental health apps are the same. For example, people’s personal data has been shared for marketing purposes and, in one case, a crisis line number in an app was wrong. The Mental Health Commission of Canada discovered that error when consulting with young people to develop Canada’s first e-mental health strategy to improve e-mental health solutions, which will be released in early 2024.

To make sure mental health apps are evidence-informed and safe, the commission also launched a Mental Health App Assessment Framework. App developers, designers, and owners can use it to assess their apps and improve their safety, quality, and effectiveness. The framework includes information as well on safety, social responsibility, and equity and outlines the perspectives of diverse groups, ages, and populations.

In addition to digital options, McCowan says talking to your family doctor can also be important. “I think it’s easy to fall into a spiral where it feels like there’s no way out. Checking in with someone, having an outside perspective, someone offering you any kind of resources, any kind of support is super helpful.”

Resource: Where to Get Care — A Guide to Navigating Public and Private Mental Health Services in Canada.

Further reading: How to Break Up With Your Therapist.

Read the entire Money & Mental Health series.

Simona Rabinovitch