Related Articles

The Canadian Mental Health Association’s Mental Health Week runs from May 5-11. This year’s theme is #UnmaskingMentalHealth and encourages people across Canada to look beyond the surface to see the whole person.

Perhaps you know the tune – about Eleanor Rigby.

“Wearing the face that she keeps in a jar by the door. Who is it for?”

In their classic song about loneliness, The Beatles sum up beautifully what it is like to live with a “high-functioning” mental illness. The song comes to mind, at times, like when I am in a bipolar mood episode, I always leave the house with my mask on. Often, this is literal. I painstakingly put on make-up, painting a face that denotes coping and professionalism (wing tips for bright eyes! Blush for pink cheeks to denote good health!). When I leave the house, I match the attitude and tone of the people I interact with, putting in enormous mental effort to calculate the actions that will make me appear “normal.”

This mask broadcasts a message of “I’m fine,” when inside, I am often anything but. When I arrive home in the evening, I wash off the painted face and watch it circle the drain, as a kind of illustration of how depleted I feel, before I fall into bed exhausted from the effort.

For me, this year’s Mental Health Week theme is a call to action. When we unmask mental health, we create the conditions for reducing stigma by promoting understanding and eliminating discrimination against people with mental illness.

Masking – what is it, who does it, and why?

Masking, also known as “camouflaging,” is precisely that – trying to blend in with societal expectations by suppressing symptoms or traits, according to Autism Canada. It is a concept that has been most studied in the context autism and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and is linked to the concept of “smiling depression,” a colloquial term for those who may slap on a smile to disguise their inner feelings.

Zachary Houle lives with autism and schizophrenia. He notes that autism has become more celebrated in the media (“autism chic” is even a thing), but he notes that the media portrayals can remove the reality and complexity of illnesses.

“I find with schizophrenia, people immediately think I’m an axe murderer or I’m dangerous and violent,” he says. “It takes less energy to pretend to be normal than going into an office knowing that I’m going to get hazed, which has happened in the past.”

Houle notes that a lot has changed in the 20 years since his diagnosis and that he is in a very progressive and understanding workplace now, but he still masks daily as it has become his second nature.

He is not alone. According to a 2023 poll from Benefits Canada, 45 percent of Canadian employees with autism feel that they have to mask their autistic traits at work.

Tanya Lepine-Darwiche, a woman who identifies as being on the autism spectrum and who lives with anxiety, agrees. “Masking is about the world accepting me being able to walk into a room and have my opinion heard without them placing judgments on me because I’m neurodivergent,” she says. “It’s putting on a performance.” She notes that it is harder to maintain social relationships when she doesn’t mask. “It’s what I need to do to be socially acceptable.”

As Houle and Lepine-Darwiche both note, masking is very useful in promoting social interaction and protecting oneself, but it also comes with costs, primarily burnout and isolation.

“I’d like to be vulnerable with people, to show them how much I trust them, but at least in the workplace I feel like I can’t do that,” Houle says. Lepine-Darwiche shared about the effects of a day of masking on her personal life, when she would come home and need a three- or four-hour nap just to recoup her energy. “It was really difficult on me and my relationship with my wife and family before I understood that all of my energy was going to masking,” she confided.

How masking affects treatment

If you are “good” at masking and continue to function, this can lead to downplaying how much you are affected by your symptoms. You, essentially, mask to yourself, and your healthcare practitioner, thus contributing to underdiagnosis and a lack of mental health supports, something both Houle and Lepine-Darwiche have experienced.

Masking also affects the level of social support that one receives. For example, when your reply is, “I’m fine,” those in your social circle cannot know that you might need extra support.

In a 2019 Ipsos study of working Canadians, 76 percent of respondents stated that they would be completely comfortable with and supportive of a colleague with a mental illness, but first they would need to know that support was needed.

The descriptor “high functioning” is not part of any diagnosis, but it is a term that captures of the reality of many. If someone imagines those with serious mental illnesses as not being able to get out of bed or go to work, that might be the case. However, for others, such as Houle, Lepine-Darwiche, and myself, we can attest to functioning adequately even when our symptoms are quite severe. Even my psychiatrist has had to learn that seeing me with my makeup done and my work clothes on, doesn’t mean that I am doing well.

Jessica Ward-King publishes under the name The Stigma Crusher to educate others about mental health. For her, this year’s Mental Health Theme is a chance to share more about what it means to mask – and to unmask – in different social situations. Sometimes that is literal – painting on an “I’m fine” face – before washing it off for the day.

Stigma, disclosure, and masking

Stigma – in all its forms – is a big factor influencing the decision to mask. According to sociologist Erving Goffman (1922-1982), those who are neurodivergent or living with mental illness will make a concerted effort to hide their symptoms – or to be “discredited” by others. Even by today’s standards, where conversations about mental health are increasingly common, many people feel reluctant to share. The same 2019 Ipsos survey of working Canadians found that 75 percent of respondents would be hesitant – or would refuse – to disclose a mental illness to an employer or co-worker due to stigma and fear of discrimination.

Goffman and others have noted how most people wear masks in their daily lives, in terms of trying to present themselves in certain ways in certain circumstances, such as on social media or at work. Putting your best foot forward isn’t the same as masking, however, where the goal is to suppress a key part of one’s identity.

For example, I experience this dilemma in another context – one of “coming out” as a lesbian, an identity that I constantly have to choose to disclose or not in a variety of situations. For example, in a conversation I can skirt around my life with my wife by cleverly using gender-nondescript language, but this brings with it a veil of inauthenticity.

Coming out about my mental illness (or not) feels similar. Do I let people in with vulnerability – or not? This is a decision that I am constantly having to make, and the solution varies with the situation, the people involved, how safe I feel, and my impression of how this “coming out” might result in negative consequences.

Chicken-and-egg situation

Without stigma, there would be little need to put on a mask to begin with, but to reduce stigma, there needs to be connections between people with lived experience of mental illnesses and other human beings – so which comes first?

While education, awareness campaigns, commemorative days, and articles like this one are effective to an extent, interpersonal contact is key according to a 2021 study in Society and Mental Health.

This, however, requires people with lived experiences to unmask, one person and one situation at a time. In other words, you need to reduce stigma to allow people to feel safe to unmask, but you need people to disclose their mental illness and unmask to reduce stigma. Chicken, meet egg.

To break that cycle, allies can play a role in creating the conditions where people feel safe to share their challenges and to open up about neurodivergence and mental illness.

For me, this year’s Mental Health Week theme is a call to action – to be my authentic high-functioning, high-performing self, and to also be okay to not be okay.

It’s also about not expending all my energy to maintain a perfectly painted mask, about not just saying “I’m fine” to make sure no one else is uncomfortable, but to feel free to say that I am struggling if I feel safe enough to do so.

When I get home from work and wash off my makeup, I want to have energy left for my family, my hobbies, and my wellness.

Outside of the home, I want to be in a world where I can take off my mask. I won’t be able to brave it every time, in every situation, and with every person – and that’s okay. The mask can be protective when the situation warrants, but little by little, unmasking can make meaningful connections to change minds.

Author: Jessica Ward-King, aka the StigmaCrusher, crushes the stigma of mental illness by being radically open about her experiences living with bipolar disorder.

Related Articles

One year after the Mental Health Commission of Canada (MHCC) was created in 2007, the non-profit established its Youth Council, a program designed to engage younger adults (18 to 30) in the MHCC’s mission to improve the country’s mental healthcare system. At the time, the Youth Council program was ground-breaking in that it signalled a move towards involving people with different perspectives and lived experience in the project of changing attitudes about mental well-being and removing barriers to accessing mental healthcare treatment.

The MHCC’s Youth Council is, at its core, an advocacy group working to amplify the voices of younger people. It’s run by folks with a commitment to positive change and helmed by Em Alexander and Colbi Mike, the council’s current co-chairs.

Colbi Mike, a young Indigenous mother, documentary filmmaker and law student from the Treaty 6 Territory in central Saskatchewan, is focused on, among other things, dismantling barriers to maternal mental health and the effects of oppression on Indigenous peoples.

Em Alexander, a queer mother of two and First Nations person with European ancestry from Newfoundland and Labrador, is passionate about mental health advocacy, as well as supporting people who have experienced trauma and those facing systemic barriers to accessing quality care.

We asked the Youth Council’s co-chairs to share their thoughts about the challenges facing young people today and how mental healthcare systems can better meet the evolving needs of people dealing with the ever-changing stresses associated with contemporary times.

Acknowledge that challenges for younger generations of adults are unique

Em Alexander and Colbi Mike

Em Alexander: People my age grew up in a very different environment than our parents and grandparents, who didn’t experience the overwhelming influence of technologies like digital media. We grew up with constant exposure to world events, which can have a big impact on young peoples’ mental health and well-being. That difference makes it especially important for mental health programs to include young peoples’ perspectives and input to be successful, engaging and meaningful to the people they serve.

Colbi Mike: Youth today face extra challenges, from our economy to mental health struggles and substance use to systemic racism. Indigenous youth, in particular, carry the burden of intergenerational trauma, and ongoing discrimination and many Indigenous mothers—honestly, I would say all—encounter systemic racism. I guess it’s just a lack of understanding of who we are as Indigenous people and where we are currently in out societal healing.

Bring more young people into conversations about mental health

Colbi says: Youth bring fresh perspective, lived experience, and innovative ideas to the table and, since they’re directly impacted by policies and programs, their involvement ensures that initiatives are relevant, effective, and empowering. Ignoring their voices in the past has led to gaps in understanding our needs. Involving young people not only builds better programming, it also fosters a sense of belonging, leadership, and accountability among young people. I think it’s imperative to involve people who’ve lived in this age of this time, and to empower them with a voice, right now.

Em says: Incorporating the voices of young people is a critical step in program development, particularly for programs that aim to serve youth. The Youth Council was established in 2008, and I consider the MHCC to be a leader in the field when it comes to including young people and people with lived experience in meaningful ways in their program and policy work. It’s so important for young people to be involved in decisions that will impact them.

Give people with lived experience of mental illness a bigger role in decision-making

Em says: It goes right back to the saying “nothing about us without us,” really. If you’re creating or updating policy that is relevant to people with lived experience, then they should be involved in that process from the start. Would you want someone to design support for you without listening to your experience or what you need, or what has or hasn’t worked before? Of course not. To get it right, you need to include lived experience. This is incredibly important in policy work because it can have lasting impacts on services, access, quality of care, and other things.

Colbi says: It’s absolutely critical to hear more from people with lived experience. Policy affects real lives and those impacted should have a seat at the table. People with lived experience have insights that professionals and decision makers might overlook, and their involvement ensures that policies are not only practical but also inclusive. Engagement also builds trust, accountability, and long-term success.

As an Indigenous mother, I have first-hand knowledge in navigating challenges such as barriers, cultural disconnect, and limited support systems. My lived experience helped me approach issues of empathy, cultural awareness, and ensure that programs and policies are grounded in real-life struggles and successes.

Em adds: As co-chair, my lived experience, both personally and as a caregiver, plays a role in my approach. My goal is to approach leadership from a trauma-informed and recovery-oriented lens, and to uplift and value the intersectional identities and experiences that our members hold. It’s been a very meaningful role for me to hold over the last several years and we operate very well as a council with respect, trust, and support.

The next steps include raising awareness, education and funding

Colbi says: Education is essential for reconciliation. Healthcare professionals need to understand the lasting impacts of residential schools, colonial policies, and systemic oppression to provide culturally safe care. While there have been efforts to include this education in some curriculum, the process is slow and inconsistent. Call to action #24 (from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada’s 94 Calls to Action) emphasizes that this is a priority, but we still need more accountability to ensure all healthcare workers are equipped to support Indigenous patients with respect and understanding.

Em says: From my own experience working at the intersection of non-profit and mental health sectors, there needs to be more support for the mental health workforce. We’re starting to see more awareness when it comes to that problem, but one of the biggest challenges I still see is good people wanting to be able to do more to help but, at a systemic level, not having the resources or capacity to do so. Sometimes this comes down to cost of services, access, wait times, or eligibility, but there’s no shortage of people wanting to support others. I sincerely hope that funding will be maintained for mental health care and related programs and initiatives throughout transitions in political governance.

We all have a role to play when it comes to providing support for people in need

Em says: When people are reaching out for support, don’t assume their identities, or their needs, or experiences – ask them, and listen with the intent to learn. It’s a challenging time right now, particularly for members of the 2SLGBTQI+ community. There are very real threats to safety for our community created by the hate and ignorance outside of our borders—and here in Canada, too. Check in on the people in your life from these groups because they are being targeted right now—BIPOC communities, 2SLGBTQI+ communities, immigrants/refugees, and others—and they need all the support they can get.

Colbi says: Mental health is deeply tied to the well-being of families and communities and yet mothers often face stigma, isolation, and limited access to safe mental health services. It’s important, therefore, to support mothers by investing in accessible and appropriate mental health care, childcare, and transportation.

We also need to keep creating programs that integrate cultural teachings and community support, because, for Indigenous people, healing often comes through reconnecting with our culture, language and communities. Investing in these areas can strengthen resilience and identity for future generations.

Author: Christine Sismondo, PhD, is a historian who writes about social issues. Her work is featured regularly in the Globe and Mail, and the Toronto Star. She is a National Magazine Award winner and the author of several books.

Related Articles

This article is part of the Catalyst series called Language Matters on terminology and usage.

Like the problem of homelessness itself, the issue of language around homelessness is complex and multifaceted, with researchers, experts, and those with lived experience asking if there is a different way of talking and thinking about housing that would drive the conversation rather than mire it in stigma, prejudice, and discrimination. Like those experiencing housing insecurity – something that can be viewed on a spectrum of risk in terms of access to and maintaining shelter – there is no one right answer.

The term homelessness can broadly encompass “the situation of an individual, family, or community without stable, safe, permanent, appropriate housing, or the immediate prospect means and ability of acquiring it,” according to The Canadian Observatory on Homelessness.

This can refer to those who are living in emergency shelters, couch surfing, living in encampments, those who are living in environments not intended for human habitation (such as cars, garages, or makeshift shelters), and those at risk of moving to these living arrangements. The definition encompasses not only income and housing, but also access to employment, health care, clean water and sanitation, schools, and childcare.

Word choice

The words we use do not, themselves, change the experience or impact of homelessness – but they can shape the conversation. For example, terms such as “houseless” or “unhoused” are emerging to place the emphasis away from the individual, and toward the bigger problem – a lack of affordable housing, something that is of great concern to 45 percent of people in Canada, as of late 2024 reporting from the Canadian Social Survey.

Al Wiebe knows these concerns. He is a housing advocate in Winnipeg who has experienced homelessness and describes himself as having no fixed address. He uses the word “homeless” to describe his experiences because, “a house is just a shelter, a roof over your head,” he says, noting that some people living in encampments, for example, may feel they have a “home” even though they are without a traditional “house.”

Further, Wiebe notes that more than 31 percent of homeless people come from Indigenous communities, with many people from within those communities noting that “unhoused” or “houseless” are more appropriate terms for those who may consider Earth their home.

Person-centred language

This term aligns with person-first language – something that focuses on the individual. For example, in the case of mental health conditions, you could describe a person as living with schizophrenia as opposed to “having” or “being” an illness, disability, or condition. In the case of housing – a lack of affordable options is the problem – not the person.

Pearl Eliadis talks about this nuance in “Turning Off the Tap: Preventing Homelessness for Victims of Violence,” her chapter in Ending Homelessness in Canada: The Case for Homelessness Prevention (2024), edited by James Hughes.

Eliadis is an associate professor at McGill University and a lawyer with more than a decade of experience, including work with the United Nations and the Canadian Human Rights Commission. She was working with Melpa Kamateros on a research project in 2021 as part of the Quebec Homelessness Prevention Policy Collaborative. At the outset, they were having a conversation on language.

Kamateros – co-founder and executive director of Montreal’s Shield of Athena Family Services – offering emergency shelter for those experiencing intimate partner violence – says care is needed in the use of the term.

“These women are not homeless, at least not as long as they are with our shelter!” Kamateros explains to Eliadis, who writes: “There is a feminist argument at play here: framing the experience of a woman fleeing violence as ‘homelessness’ places the focus of the policy problem on her; it reframes who she is, even though her circumstances were the product of someone else’s violence. The woman may be temporarily unhoused, but that does not make her ‘homeless’.”

Evolving ideas

Some sources, such as Regeneration Outreach in Brampton, Ontario use “homeless” to refer to someone with no fixed address and “houseless” to refer to someone who does not have a traditional home, but does have a place to stay, such as an RV or other non-permanent structure. Blanchet House in Portland, Oregon uses both “houseless” and “unhoused” interchangeably over the more stigmatized term, “homeless.”

However, as advocates are noting, changing the terms may eclipse the bigger issues.

“Even the benefit of switching from a word loaded with negative connotations to one that is denotationally the same thing but without those connotations only has a negligible benefit that lasts a few years, until stigma grows on the new word too,” wrote Frances Koziar, a young, disabled, retiree, and a social justice activist living in Kingston, Ontario in an Ottawa Citizen op-ed.

While language continues to evolve, it is only one part of a much larger issue. The debate over terminology should not be used as a form of virtue signaling without meaningful efforts to tackle the deeper challenges of housing affordability, mental health, and substance use.

Further reading: A Roof of One’s Own: The lack of housing options brings its own kind of homesick feeling.

Jessica Ward-King researches and writes as The StigmaCrusher. She feels most at home when learning about and advocating for mental health.

Related Articles

If you’re in certain filter bubbles, it can feel like mental health is everywhere. “So many people are consuming mental health information, but without a critical eye,” says Jessica Ward-King a self-described fierce mental health advocate with a PhD in experimental psychology who uses the moniker The StigmaCrusher (“heavily educated and heavily medicated”). She uses online talk therapy and also finds information through TikTok and YouTube. “I consider that e-mental health too,” she says. Ward-King informs her influence with research from her doctoral studies, her lived experience with bipolar disorder, and other evidence-based sources, but this isn’t necessarily the norm for online mental health.

Technology is undoubtedly transforming the way people in Canada receive health care with countless applications, influencers, and digital tools popping up everywhere, but how does one sort through the many options?

“E-mental health services in Canada provide crucial benefits—offering anonymity, reducing stigma, and allowing people to access support in ways that work for them,” says Maureen Abbott, Director of Innovation at the Mental Health Commission of Canada. “Whether it’s the flexibility of choosing their own time and format or the ability to find help in urgent moments when in-person services are unavailable, e-mental is transforming mental health care. One individual shared with us that accessing a peer support group in the middle of the night literally saved their life,” Abbott says.

Maureen Abbott, Director of Innovation at the Mental Health Commission of Canada at the Electronic Mental Health International Collaborative (eMHIC) conference in Ottawa in September, where the strategy was launched. With countless e-mental health solutions available, clear guidelines are essential to ensure clinical quality, user safety, and data security. Photo: eMHIC.

A strategy for the future

The Mental Health Commission of Canada launched Canada’s first E-Mental Health Strategy in 2024. It provides guidance for the development of e-mental health with emphasis on clinical safety, frameworks for data collection and retention, and culturally appropriate care.

“While e-mental health services offer many advantages, challenges like privacy and service quality must also be addressed. That’s why the Mental Health Commission of Canada, with the support of Mental Health Research Canada, developed a national strategy—shaped by a diverse advisory committee, with more than half the committee comprised of those with lived experience of mental health challenges,” Abbott says. “This guiding star document sets priorities for the future of digital mental health, ensuring meaningful engagement and collaboration across the sector.”

By supporting those creating e-mental health policies and solutions, the MHCC can inspire and improve the field at a systemic level ensuring that best practices cascade through to app developers, policy makers, and healthcare leaders and empower them to establish and adopt standards that will improve user outcomes.

In this way, it is a strategy that meets people where they are – because e-mental health keeps growing. According to the American Psychological Association, in 2021, more than 20,000 mental health apps were available on the market.

The proliferation is bound to continue because e-mental health tools can offer greater choice, convenience, lower cost, and, in some cases, higher-quality care than traditional services, according to an editorial called The “Uberisation” of Mental Health Care: A Welcome Global Phenomenon? by Ian Hickie, professor of psychiatry, Brain and Mind Centre, University of Sydney, Australia.

“If those with lived experience and research capacity in this field don’t respond appropriately, it leaves room for others to step in to respond consumer priorities: access, choice, competitive pricing, and user experience. Worldwide, demand for personalized mental health services far outstrips supply,” Hickie writes.

Here in Canada, the E-Mental Health Strategy serves as a blueprint, offering six recommendations and 12 priorities to chart the future direction of development of e-mental health in Canada and drive innovation – with consideration.

For example, one priority is to address the quality of e-mental health solutions and services, including privacy and data protection concerns. The strategy references the First Nations principles of ownership, control, access, and possession to guide health leaders, provinces and territories, jurisdictions, community organizations, and researchers around consent, collection, and data sovereignty.

“Trust is at the heart of e-mental health,” says Michel Rodrigue, president and CEO of the Mental Health Commission of Canada. “The efficacy and safety of e-mental health apps and supports should be paramount. People in Canada need assurance that these options meet the highest standards of safety and quality, prioritize equity-first data governance, maintain confidentiality, and include the perspectives of people with lived experience of mental health challenges.”

Stigma Crusher Jessica Ward-King notes that when people are in the midst of a crisis or struggling with their mental health, they may not be necessarily asking about how their data is being managed.

“Privacy is a huge concern that many don’t even think about,” she says. “Safety is another big issue. If a chatbot responds to suicidal thoughts, what protection is in place? If you’re getting advice from someone who doesn’t know your medications, what’s the risk there? A strategy makes sure someone is asking those questions before they become problems.”

Some of the recommendations in the strategy touch on issues of workforce and user readiness. People want help determining the quality and safety of options when there are so many options and no common standard. As e-mental health solutions continue to improve in quality and efficacy, there needs to be a means of communicating about evidence-based solutions with practitioners and to prove that they are both safe and efficacious.

With the speed of change, the e-mental health community is calling for specific guidelines related to AI use in mental health care; something that goes deeper than existing domestic and provincial guidelines and standards on the ethical use of AI in Canada.

Throughout the strategy-development consultations, the creation of a mental health app library and assessment process was one of the most discussed topics among both international experts and domestic collaborators. A database for assessed apps and a national assessment process would directly address some of the largest issues facing e-mental health in Canada, along with ongoing reviews and updates of best practice guidelines, since technology, legislation, and research evidence are constantly changing, particularly in relation to data security and privacy standards.

Addressing risks and readiness

E-mental health can offer access to care for people in rural areas who may not be able to travel to a care provider. It allows people to find culturally appropriate care for their situation, preserves privacy, and is usually less expensive than in-person services – for both the provider and the user. During the peak period of the pandemic, electronic mental health solutions allowed people to access care while physically distancing, isolating, or recovering from COVID-19.

Virtual consultations for mental health, substance use, and healthcare services went up during the spring and summer of 2022, with nearly three in five people in Canada accessing care this way, according to Statistics Canada.

According to a 2021 Canada Health Infoway survey, 63 percent of people said they would not have sought mental health care if virtual options had not been available.

Shaleen Jones knows this firsthand. She is the founder and executive director of Eating Disorders Nova Scotia, a community-based charitable organization that offers all of its services without a referral or a diagnosis.

Like many organizations, Eating Disorders Nova Scotia became 100 percent virtual in 2020, delivering all their services, supports, and training online, something that allowed the organization to expand its reach, says Jones.

“Technology is really a tool that allows us to connect with others – I believe it is that personal connection that has the greatest impact,” she says. “Like any new tool, thoughtfulness in how it is utilized is critical. The MHCC e-mental health strategy serves to identify potential challenges and strategies as we work to chart the future course of e-mental health services in Canada.”

Canada’s First E-Mental Health Strategy: The Six Priorities

- Improve perception, awareness, and engagement in e-mental health.

- Develop resources for evaluating the effectiveness of e-mental health solutions and programs.

- Address the quality of e-mental health solutions and services, including privacy and data protection concerns.

- Reduce barriers and address system challenges to e-mental health solution adoption.

- Embed IDEA (inclusion, diversity, equity, and accessibility) principles in all e-mental health development, tools, and delivery.

- Support the mental health workforce to integrate e-mental health into their practice.

Canada’s First E-Mental Health Strategy: The 12 Recommendations

- Advance the development and promotion of a readiness assessment tool for service providers.

- Develop and launch comprehensive e-mental health training for the mental health workforce.

- Advance and promote a best-practice guideline for using e-mental health tools.

- Increase safety with the use of artificial intelligence in mental health care.

- Develop a national mental health app library.

- Establish a champions network.

- Develop a navigation site and public awareness campaign for quality e-mental health solutions.

- Leverage e-mental health to support the continued utilization of interdisciplinary health-care teams, including mental health professionals.

- Consider the role of e-mental health in Canada’s high-speed bandwidth initiatives.

- Invest in the development of e-mental health solutions for a spectrum of intensity of services.

- Allow for e-mental health solutions in all funding models for provincial and territorial health systems.

- Advance interoperability of mental health data between providers and personal data ownership.

Further reading: Find the strategy in full.

Resource: E-Mental Health: What is the Issue?

Author: Fateema Sayani is the manager of content at the Mental Health Commission of Canada.

Related Articles

Debra Slater is the type of person you want looking after your loved ones. A self-proclaimed born nurturer, she took care of her grandmother in Saint Vincent and the Grenadines and went to school to become a personal support worker (PSW) after moving to Canada. Slater loves talking to and learning from the older adults under her watch at a long-term care home on the outskirts of Toronto. She greets them by name, with eye contact and a smile, and strives to develop a rapport regardless of their cognitive condition. She treats clients as individuals while helping with activities of daily living – often referred to as “ADLs” in support work communities – such as bathing, getting dressed, and eating.

“You need to take time to understand their emotions and feelings,” says Slater, who has worked as a PSW on and off for more than 20 years. “You kind of become their family. They’re not ‘my patients.’ They’re people who want to be as independent as possible and this is their home. My job is to bring comfort and peace, love and companionship. It’s a whole vibe.”

Debra Slater, a personal support worker, also coordinates the Empower PSW Network to advocate for better working conditions.

Slater maintains this attitude even though, on a typical shift, she has eight residents with diverse needs to juggle. One might have had a rough night; another could be dealing with a medical issue; and if any of Slater’s colleagues are absent, she’ll probably have additional clients. “On a difficult day, you have to work harder to be present,” says Slater, reflecting on all the de-escalation and problem solving she must do. “That takes a toll. My mental health is a roller coaster.”

Many care providers are in this profession because they have similar nurturing mindsets, yet 80 percent have considered changing careers, according to a report published last year by the Canadian Centre for Caregiving Excellence (CCCE).

Across the country, PSWs, direct support professionals (DSPs) – who work with clients with disabilities – and other paid health-care attendants are feeling stressed, overworked, and underpaid. The labour pool consists largely of racialized women, many of whom are newcomers to Canada, and they face high rates of abuse and discrimination on the job.

Working in congregative living facilities and providing home care for a patchwork of public and private employers, the majority are essentially gig workers without benefits such as paid sick days or access to counselling.

Fewer than half of the PSWs surveyed by the joint University of Toronto and St. Michael’s Hospital-based Upstream Lab said their health was good or excellent, which is lower than the national average. More than 20 percent likely had some form of depressive disorder, the researchers concluded in a 2022 paper, “significantly exceeding the prevalence of major depressive episodes among Canadians.”

In a country with an aging population, this is a significant challenge. If we don’t take care of PSWs and other care providers, how can they be expected to look after our most vulnerable citizens?

Risky business

More than 650 PSWs in the Greater Toronto Area responded to the Upstream Lab survey, which found that:

- 97% are born outside Canada.

- 86% are precariously employed.

- 89% lacked paid sick days.

- 90% are women.

- Many are casual employees, with wages that range from $17 per hour in home or community care to $25 per hour in public long-term care facilities.

This snapshot is representative of care providers across the country, according to the Upstream Lab paper, and their precarity is “significantly associated with higher risk of depression.”

Health-care jobs in Canada have traditionally been secure, but over the last three decades, “disparities in pay and work conditions have grown between registered professionals (such as physicians, nurses) and other staff whose jobs are part-time, temporary, on contract and not unionized,” the researchers wrote. A national focus on discharging people from acute care and aging in place has ramped up the demand for PSWs, who now constitute about 10 percent of all health-care workers. This workforce grew relatively quickly, says Upstream Lab director Dr. Andrew Pinto, without much scrutiny or consideration of the consequences.

These poor working conditions can be detrimental to physical and mental health, says Dr. Pinto, who, in addition to his role as a public health specialist, is also a family physician. In a system that incentivizes “reducing costs” and “doing more with less,” he says that many PSWs fear reprisal from their employers if they raise concerns about problems on the job. Pinto knows this from his research, and from the PSW patients he sees as a physician. “They’re really dedicated to caring for others and take pride in their work,” he says, “but they’re not given the respect they deserve.”

Dr. Andrew Pinto: Better working conditions lead to better health outcomes. Photo by: Upstream Lab

Despite economic and demographic pressures, Pinto believes this system can be reformed. Because it’s funded predominantly by the public, a collective push for “a basic set of rights” — living wages, paid sick days, access to health resources, opportunities to flag systemic issues — will improve conditions for care providers, whether they work for government or private employers. “The public doesn’t want gig workers looking after their loved ones,” says Pinto. “Better quality jobs will not only improve the health of PSWs, they will also improve care and health outcomes for all Canadians.”

To continue the campaign for policy reform, the Upstream Lab’s research project has spawned the Empower PSW Network, a coalition of care providers seeking to raise awareness and advocate for change. Slater, the network’s coordinator, says that foremost, PSWs need more structured support. “It’s not the work that’s the problem — it’s how we’re treated.”

The silent treatment

Liv Mendelsohn, executive director of the CCCE, knows PSWs who live in their cars because they can’t afford housing. She’s heard stories about the stress of rushing between nursing homes and private residences from PSWs who cobble together gigs. “We rely on them to provide really intimate care,” she says, “but we don’t do enough to support their health.” Moreover, because a care provider’s permission to be in Canada can be tied to a particular employer, they often remain silent when facing discrimination or exploitative situations.

The CCCE has called on the federal government to implement a $25 per hour minimum wage for all PSWs. Mendelsohn also emphasizes the need for consistent benefits to prevent burnout and reduce the number of PSWs migrating to jobs in acute care for more stability. Despite the scale of this transformation, she’s hopeful. “We can’t not improve things,” she says. “There’s no way our system can continue without better support for PSWs.

“We don’t just need bodies,” adds Mendelsohn, envisioning a new era in which, for example, a senior with dementia is cared for by the same provider every day, improving their quality of life. “We need skilled, compassionate people and we need to acknowledge that they’re a critical part of our health-care system.”

In a different world, Kezia (last name withheld to protect her employment prospects) could have been one of those providers. Born in India and raised in the Bahamas, she moved to Prince Edward Island for university and supported herself by working as a DSP and PSW. Kezia assisted with ADL, cooked, cleaned, and accompanied clients to day programs and medical appointments. The learning curve was steep, but with supportive co-workers, she got into a groove. “We tried to foster a feeling of being at home,” she says. “After a while, it felt like a calling.”

But Kezia, who was in her early 20s at the time, also experienced racism and inappropriate sexual comments. Telling her manager about problems “was like hitting into a wall.” She felt unappreciated by her employers, even after working a 16-hour shift. If she missed a shift, she didn’t get paid, which meant she might not have enough money for rent or groceries. Exhausted, she was neglecting her own health. After three years, Kezia left the profession.

“If we were treated better, I might have stayed,” she says. “PSWs are the backbone of our health-care system, but I can never go back to working in the that field.” Instead, Kezia is going to school again. She’s studying to become a nurse.

Further reading: Mental Health at Work: It Matters: How to Start the Conversation.

Learn more: Caregiver resources from the Canadian Centre for Caregiving Excellence (CCCE).

Related Articles

In 2009, experienced kayakers Zac Crouse and Corey Morris were descending a rain-swollen river in Nova Scotia when Morris was swept over a waterfall and died. At the time, the men were planning a kayak expedition from Ontario to the Atlantic Ocean. Traumatized by the death of his close friend, Crouse entered therapy and began taking medication, and two years later, he embarked on a 1,500-kilometre solo journey as part of his healing.

“At a basic level, it was a physical challenge, but there were also higher-level cognitive things happening,” says Crouse, who used to work as a recreational therapist and now teaches rec therapy in a university program. “You get into a trance-like state after so many hours of paddling. Your brain is seeing patterns on the water that don’t easily fall into slots and boxes. You’ve also got the sounds and feel of the wind. There’s a calming effect,” he says.

“The repetitive motion, the exertion, all the little things you have to pay attention to in order to make progress — those create a sense of flow,” Crouse adds. “And the problems you’re solving are very basic and immediate, not future vague ones.”

Crouse’s trip provided a break from rumination and regret. It helped him recover. And although people experience and respond to trauma in different ways, his journey exemplifies the curative potential of “blue space.”

Zac Crouse teaches recreational therapy. He took a long kayak journey to help with healing after the death of his close friend, Corey Morris.

Second nature

The benefits of hanging out in nature are well-documented: lower blood pressure and stress-hormone levels, less anxiety, more self-esteem. Now, a growing body of research suggests that spending time in, on, or near water can have a more positive impact on our health than other outdoor settings. A 2022 paper, published by a pair of University of California, Davis psychology researchers, for example, concluded that even looking at a creek or pool is enough to lower blood pressure, improve heart rates, and increase relaxation among respondents, a result they attribute, in part, to the evolutionary link between successfully detecting drinking water in arid environments and stress reduction.

Aquatic environments can also be hazardous, of course. Drowning is the third-leading cause of unintentional injury death around the world, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Flooding is among the deadliest consequences of climate change, and it tends to displace or kill those with the least capacity to escape or adapt. Yet, as a species, we have a deep-rooted biopsychological bond to this molecular combination with two parts hydrogen, one part oxygen. Over the past decade or so, researchers have begun to deconstruct the affinity we feel for water, and they are exploring how integrating blue space into our communities and lives could pay tremendous dividends.

According to environmental psychologist Jenny Roe, director of the University of Virginia’s Center for Design and Health, blue space has four triggers that activate the human parasympathetic nervous system, a network of nerves that relaxes our bodies following stressful or dangerous experiences.

First, water instills a sense of being away. It can be either tranquil or dynamic, conditions that can make you introspective or dialed in to your surroundings, both of which serve as escapes from habitual behaviour.

Second, blue space – especially large bodies of water – conjures a feeling of “extent,” of being in a boundless environment where possibilities feel limitless. Although one can also experience these glimpses of an infinite existence while, say, hiking up a mountain, they’re amplified in blue space by acts like looking to the horizon or into the depths of a lake.

Third, the sounds and sights of water — as it runs over rocks, for example, or dances in the sunlight — can spark “hard fascination,” a concentration of our focus through stimulation, and “soft fascination,” an unconscious partial capturing of our attention that requires little effort and frees the mind to roam. Both can contribute to restoration. And fourth, water confers a sense of compatibility with our location; of comfort and belonging.

Author and stand-up paddleboarder Dan Rubinstein departing from Ottawa in June 2023 at the beginning of a 2,000-kilometre journey to explore the curative potential of blue space — an expedition that formed the basis of his upcoming book, Water Borne. Photo: Lisa Gregoire.

Flow states

Another environmental psychologist, Mat White at the University of Vienna, is arguably the world’s leading authority on blue space. He studies what happens when we do anything (paddle, swim, surf, walk, sit) around any type of water, from vast oceans to urban fountains. After leading several research projects and crunching some big numbers, White has concluded that these environments provide a boost by offering increased opportunities for both stress reduction and physical activity.

For one paper, White analyzed a UK census of approximately 48 million adults and found that the closer people live to the coast, the healthier and happier they are. “The crucial point about that research was that it was the poorest communities and individuals who got the benefits,” he says, referring to both mental and physical health. “If you’re rich, it doesn’t matter how often you spend time in blue space. You’re healthy and happy anyway. But if you’re poor, it matters hugely.”

The idea that a place with specific environmental attributes can reduce socioeconomic health inequalities is called equigenesis. Rich Mitchell, a population health researcher at the University of Glasgow, coined the word after publishing a paper that suggested income-related health disparities were less pronounced in neighbourhoods with better access to nature.

The quality of blue spaces affects their therapeutic properties, according to White, as does how we interact with them. Those variables are influenced by geography as well as cognitive and cultural differences. For example, people often prefer places they visited as children, and there are dramatic differences between walking and sitting, and different outcomes depending on how close we live to a blue space and how frequently we visit. But on the whole, when we’re near water, we tend to lose track of time and be more active, and every extra minute of movement is good for our health. “The goodness isn’t just the water,” says White, explaining that people tend to enjoy quality time with one another at places like beaches because of the sense of belonging they feel. “It’s a behavioural interaction that water encourages. This is one of the reasons we think blue spaces tackle health inequalities. They’re social spaces that draw us into cross-generational play.”

New depths

The kicker to all of this, the multiplier of multipliers, is that time spent in blue space, especially by children, promotes pro-environmental behaviour, which is another way of saying “taking better care of the planet.”

One of White’s frequent collaborators, British landscape architect Simon Bell, came up with the term “blue acupuncture” — basically, adding a splash of blue space to a community to help improve public health. For example, a recent project in a low-income neighbourhood in Plymouth in southwest England transformed a small neglected beach into a launch for personal watercraft, swimming area, and park with views of the harbour. The cost was around $150,000 USD and surveys assessed the well-being of area residents before, during, and after construction. Psychological health increased, as did perceptions of community cohesion. Families played in the park, seniors sat on benches, and teenagers took forays into the sea.

What does all this have to do with Zac Crouse’s kayak journey? The common denominator is water. Paddling all day helped Crouse’s brain “catch up to reality,” he says, supplanting a traumatic experience with new memories. But even if one’s connection to blue space is more subtle — a picnic beside a pond, a sunset stroll along a river — it can provide a restorative break from the tensions of daily life. These benefits are not a panacea, but because they “apply to millions of people,” says White, “the overall public health benefit is huge.”

Adapted from Water Borne: A 1,200-Mile Paddleboarding Pilgrimage by Dan Rubinstein, forthcoming in June 2025 from ECW Press.

Further reading: Good Grief: Is there a right way to grieve—and for how long?

Resource: Where to Get Care – A Guide to Navigating Public and Private Mental Health Services in Canada.

Author: Dan Rubinstein

A writer and stand-up paddleboarder based in Ottawa, Canada. His latest book, Water Borne (2025), chronicles his 2023 paddleboarding expedition from Ottawa to Montreal, New York City, and Toronto, exploring the deep connections between water, health, and community. Dan’s work, featured in publications such as The Walrus, The Globe and Mail, and Canadian Geographic, often focuses on outdoor adventures and the environmental importance of blue space.

Related Articles

The Book Club series profiles good reads that challenge stereotypes and stigmas.

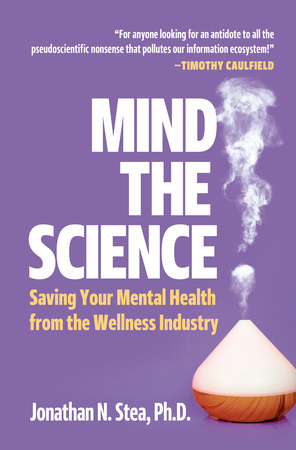

I imagine Jonathan Stea has an “I Heart the Scientific Method” fridge magnet because his book, at times, has the ring of your high school science teacher trying to drum up enthusiasm for the concept to a tough crowd. Eventually it may land.

Mind The Science

Stea comes by it honestly. He is an adjunct assistant professor in the department of psychology at the University of Calgary and a full-time practicing clinical psychologist. He frequently takes to social media to debunk myths and correct facts. (Sometimes his mom even hops online to take on the trolls).

He writes for a lay audience with nuance, avoiding finger-wagging or dumbing-down tones. Stea offers compelling stories along with an overview of how to evaluate research and explains the importance of assessment, testing, peer-review, and various research methods. It’s solid information.

Except that he is battling a tide of speedy hot takes in our online world – a vast hyper-verse of snake oil-type claims from innumerable self-appointed “experts” in physical and mental health, celebrity endorsers, and others that cluster under the all-encompassing nebulous term “wellness.” It’s a vast and largely unregulated domain where many an influencer can hang up their shingle and freely offer tips that can range from cutesy to deadly.

Is it all bad? No. For example, you can shell over good money for a menu plan that aligns with the season and sounds vaguely spiritual. It likely tastes great and offers a cozy kind of comfort, but then there are more grim cases like that of Kirby Brown who attended a “Spiritual Warrior” retreat in Arizona. In 2009, Brown and two other participants died in the final activity of the retreat, a poor imitation of a Native American “sweat lodge.” Twenty other participants were taken to local hospitals.

Consumer safety

The Brown family focused their grief into an organization called SEEK Safely, designed to educate the public about the potential harms of the wellness industry, provide consumer information, and promote safety and accountability. Stea details their story in the book subtitled, “Saving Your Mental Health from the Wellness Industry.”

What might we need saving from? Well, it depends. Stea writes with humility about humanity – recognizing our contradictions, flaws, and changing circumstances. He shares his personal experience of caring for a loved one, grappling with the frustration of ineffective treatments. As a young person, he felt bewildered by science’s limitations. How is it that something capable of sending a man to the moon could also leave those closest to you in “a fog of health uncertainty”? he asks.

As a fellow mere mortal who will eventually fall sick, Stea wonders what he might do in the future. “Will I reach for the healing crystals? Maybe. Desperation is intoxicating.”

That vulnerability in moments of crisis can leave people open to being exploited at a time when they may be seeking growth, deeper meaning, connection, and a soft place to land in a world that is chaotic and confusing. Moreover, ineffective treatments can produce harm, drain your pocket, and erode trust in scientific foundations. At the same time, Stea notes, some wellness treatments may provide coziness and a sense of warmth in a fragmented healthcare system that may not have time for comfort or calm bedside manners. It’s a matter of knowing the difference.

More than just fluff: Is your therapist real or a feline? The case of George the Cat illustrates the importance of understanding how wellness practitioners are regulated in your jurisdiction.

Stea seems hopeful and offers faith in people’s capacity to sort through piles of information. I try to share that view, but more often I wonder about our ability to constantly evaluate the material coming at us in order to make informed decisions.

Do most people, moving through life at breakneck speed, pause to reflect on their “favourite” thinking errors and logical fallacies? I am fond of self-awareness, but not everyone may have it at all times, or in moments of heated exchange, the kinds that are perpetuated by online interactions and algorithms.

The key is to develop it. “This awareness is our friend when trying to figure out the legitimacy of particular mental health-related assessments, diagnoses, and treatments,” Stea writes. In addition to quantitative and qualitative scientific methods, Stea talks about Indigenous ways of knowing as something not to be co-opted as well as the value of lived experiences, where people share subjective takes on their lives, events, and ideas.

Things to watch for

Stea offers helpful tips for developing science literacy, and includes a lay overview of randomized control trials, and other evidence-based processes. He warns of pseudo-clinical jargon that masquerades as science but does not adhere to research methods. A key flag – the evasion of peer-reviewed studies.

“Science is a self-criticizing machine,” he says. “Peer review essentially involves having experts in a scientific field grade each other’s work and decide if it passes or fails,” he explains. “People who promote pseudoscience are experts at dodging the peer review process. They will either avoid it entirely or self-publish on blogs, websites, newsletters, or social media. They will claim that their pet theories cannot adequately be tested with current scientific methods, or they will claim that the ‘scientific establishment’ is biased against them,” he writes.

Stea demystifies the concept of science overall, noting that it’s something to regard as a tool or process and not something to believe in, he says. “Science isn’t a God. Or a unicorn.”

Healthy skepticism

To stem the tide, Stea offers an easy-to-implement practice – tame your search bar. Essentially, he explains, it is like going to the grocery store and avoiding impulse buys. The key: Go with a list. “Why are you looking online? Knowing what you need – such as ways to improve your health or a therapist – can keep you out of rabbit holes,” he says.

Thinking critically about information is a helpful skill when navigating an overwhelming online landscape and if you need a reminder, you can make George the Cat your screensaver. The domestic orange-and-white housecat was registered as a hypnotherapist with three UK industry bodies by a BBC journalist, exposing the flaws of certification and credentials. This example, while amusing, can serve as shorthand. “We all fall for fake science news at times to varying degrees, and it’s easier in hindsight to see what went wrong,” Stea writes.

Learning from those errors and developing media and scientific literacy can offer a sense of structure and control, as fake science news continues to perpetuate.

Further reading: Book Club – All in Her Head: How Gender Bias Harms Women’s Mental Health.

Resource: Online Disinformation: If it raises your eyebrows, it should raise questions.

Author: Fateema Sayani feels like “regression analysis” can be used ironically, these days. She frequently writes The Book Club section for The Catalyst.

Related Articles

Black History Month 2025 is focused on Black legacy, leadership, and uplifting future generations, a topic we’ve explored in The Catalyst through stories on rallying or searching for culturally appropriate care. In this piece, we ask how more equitable futures can be made possible through design for African, Caribbean, and Black communities, and others not represented by the “average.”

I was grocery shopping when a clerk approached and started processing my cart at the self-checkout. It was quiet. I didn’t ask for help, and she didn’t ask if I needed any. She just stood next to me and started putting my items through.

Some people might say that this is good service, but it didn’t feel that way. It felt like she thought I was too stupid or slow to understand how to scan my items. She didn’t approach other shoppers; a young man at one checkout and a mother with a small child at another. So, based on my past experiences, I wondered if she thought I would try to steal the groceries.

I am Black, and I’ve been followed through stores on more than one occasion. Yet my items were neither subtle nor expensive: paper towels, a bag of rice, and a few other items –hardly the slip-it-into-your-pocket selection. It also wasn’t busy enough for me to go unobserved, so what was the deal?

Then, another thought occurred to me as I was leaving, and she made her way over to “help” another client who had not asked. What we had in common was grey hair.

Bias is two steps forward, one step back

I wanted to sigh and dismiss it, but the more I thought about it, the more aggravated I felt. How many biases against you are too many?

I’m comfortable in my skin, doing what I love and doing it well, so why did that clerk bug me? Because her actions belittled me; they made me feel less. It upset me and I’m not alone.

According to an American Association of Retired Persons study, almost two out of three women age 50 and older in the U.S. report they are regularly discriminated against and those experiences impact their mental health.

Women – particularly women of colour – carry the burden of intersectional prejudices of age, ethnicity, gender, and socio-economic status, among others.

If you’re thinking, yes, but that’s the U.S., then know that in Canada, we face a similar picture. A 2024 Women of Influence survey found that eighty percent of women say they experienced ageism in the workplace. An equal number witnessed women in their workplace being discriminated against based on age.

How do they know? It shows up as being ignored when providing advice and then having the same advice applauded when it’s delivered by a younger or male colleague. It’s the snide comments, being passed over for promotion, or any number of things that make them feel unheard, unseen, or incapable.

Average Has Never Worked

Presumably, most people don’t think ageism, sexism, or racism are attributes to aim for, but beyond the morality considerations, the health costs, and the societal impacts, there are bottom-line business costs that come with these biases.

Sharon Nyangweso, founder and CEO of QuakeLab, a niche agency that applies an equity lens to solve corporate and social challenges, puts it best when she says that we need to see equity as a technical skill.

“Long gone are the days of effective business leaders seeing equity as a ‘nice to have’ or social thing done for a few employees,” she says. “Equity is about building better products, services, and processes. It’s about not injuring or killing people because we can’t see beyond the needs of the ‘average person.’”

Take, for example, pulse oximeters. These small sensors are clipped to a finger or toe and use light to measure oxygen saturation in the blood. They are everywhere. According to Fortune Business Insights, the market was valued at $2.24 billion in 2023 and is expected to grow to $3.56 billion by 2032.

It’s been known for decades that everything from skin pigmentation and melanin to nail polish affects a pulse oximeter’s ability to accurately measure oxygen saturation. For Asian, Black, and Hispanic patients, this can lead to inaccurate readings. Further, those inaccuracies may also be associated with disparities in care, according to the Journal of the American Medical Association.

“Would you call that device effective?” Nyangweso asks. “Would you say that someone who engineered a product that didn’t work for its intended audience was a good engineer? When equity is integrated as a skill set, it considers all people in the design process, and that produces better, truly universal products, processes, and services.”

Say what?

Our stores are filled with products that unintentionally fail to serve their intended audiences. If you’ve ever failed to get a response from an AI-assisted audio device because you have an accent, you quickly understand what it means to use a device created for “the average” user.

What happens when we use AI devices to make decisions that impact people? So far, we know that it can wrongfully send more Black people to prison, inaccurately predict healthcare needs of Black patients, produce sexualized images of Asian women, program ageism into job application processes, and the list goes on. AI isn’t awful, it’s just built with our societal biases.

It’s not just AI. We have smartphones, cars, fitness trackers, and knee prostheses built for men – although women and other genders are also users. Given that women are the primary decision makers for consumer purchases, representing 70–80 percent of all consumer spending and representing about half of the population, how is that effective design?

This is what comes from building for the “average,” which is code for white males. It’s an approach that results in ineffective products, processes, and services that show a bias against their target market.

Even more amazing, products built for the average white man don’t properly meet most of their needs either. Flip through The End of Average by Todd Rose to learn more about that.

Equity as a Required Skillset

When you operate in an environment that doesn’t fit you, or support you, and indeed seems engineered to harm you, it takes a toll. That’s in part why there is often an emotional layer that comes with discussions of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI).

Nyangweso described the intersection this way, “People have conflated the work that we do in this field with morality or moralization and that mixes things up and distracts us from talking about the problem we are trying to solve. Instead of addressing the issue the way you would any workplace challenge, people expect me – someone who works in this field – to be their assessors or the morality police,” she says.

“We need to force the question of equity to be a question of professional obligation and responsibility. I want to walk into the room as a professional. I’m not there to talk about everyone’s feelings. I’m not there to beat back decades of socialization.”

Not only is that an impossible task, but it distracts from the real work of DEI by placing an emotional burden on the people trying to fix real problems that create tangible threats to patients, consumers, and clients.

“To understand equity as a technical skill, and to do the work of the field, you have to appreciate the three segments or aspects of DEI work,” Nyangweso says, listing them as:

- Equity as an intellectual activity or academic process.

- Activism.

- Professionalized equity.

Equity as an intellectual activity or academic process means research and data. For example, saying ageism is an issue can’t happen until someone does the work of measuring perceptions and impacts.

Activism, as Nyangweso describes it, is “that practical process where we are trying to reach liberation in the world.”

This work calls into question the status quo, forces us to have conversations about things we took for granted, and eventually leads people to question the way we do things and why we do them. It is the emotional lift that starts the ball of change rolling. How many conversations were prompted by Black Lives Matters or Every Child Matters?

Professionalized equity falls within change management tactics and is often how organizations implement the change processes required to become more equitable producers, suppliers, and employers.

Nyangweso notes that there are multiple intersection points with the three. “The work of activists supports the DEI sector, and makes professionalized equity work possible, and research is used to inform practices and approaches.”

All three segments are valid and serve different purposes. When we default to one without consideration for the others, then real change is not just hampered, it can become impossible. Similarly, when we try to use the tactics for one, to implement another, we will be disappointed by the results. For instance, using the tools of activism to develop tactics for professionalized equity will leave us frustrated by the constraints of a corporate environment and the speed of change.

Equity works

All workplaces do better when psychological safety, a byproduct of equitable spaces, is present. Psychological safety is about feeling free to be who you are at work. It’s about being able to engage without fear of punishment or other negative consequences. For employers, it not only improves the workplace environment, but psychological safety also means financial advantage through increased productivity and lower absenteeism and turnover.

We all live with the challenge of managing within an inequitable world. We can perpetuate those inequities by pretending they don’t exist, don’t impact us, or those around us – or we can take the initiative and make changes where we’re at. We can question why we ignore the advice of older employees; we can call it when we hear inappropriate comments about people based on age, gender, race, sexual orientation, or anything else that doesn’t reflect respectful engagement.

The absence of equitable thinking in the development of work has real world consequences. To do your job effectively, whether you’re a grocery store clerk or a product developer, you need to learn, understand and live diversity, equity, and inclusion.

Further reading: Rallying While Black.

Resource: Psychological Health and Safety Training and Assessment.

Author: Debra Yearwood looks for silver linings – and not just in her hair – she is the Director of Marketing & Communications at the Mental Health Commission of Canada.

Illustration by Holly Craib

Related Articles

If we gave The Catalyst magazine a sub-theme for 2024, it would be Learning and Listening. Stories covered lived experience of mental health and new approaches to therapy, as well as deeply insightful reflections on wellness, mental health research, and new ideas. If you missed some of these stories in 2024, we welcome you to take a tour through the magazine with notable highlights from the year that was. Happy 2025.

Good reads and recommendations

Books on mental health cover the gamut from research to personal tales, to a combination thereof. The Book Club series looks at works by Canadian authors, exploring the sub-themes and ideas. For example, the book Lifeline: An Elegy by author Stephanie Kain, centres around the author’s complicated relationship with a woman diagnosed with suicidal depression. Kain writes about the indignities of a locked ward, having to administer heavy medications, supporting someone through the after-effects of electro-convulsive therapy, and her own well-being. This article about this book received a Canadian Online Publishing Awards nomination. The awards will be announced in February 2025.

Read it: https://mentalhealthcommission.ca/catalyst/book-club-lifeline-an-elegy/

Have you picked up a copy of All In Her Head: How Gender Bias Harms Women’s Mental Health? In it, author Misty Pratt shares her story of a nervous breakdown, anxiety, and depression; her strategies, sessions with therapists, and how these intersected with life stages, such as the birth of her children. The Ottawa author and science researcher weaves in her lived experiences with trenchant analysis of contemporary research through a biopsychosocial lens (a model that looks at biological, psychological, and social factors that influence our lives). It’s a great read with captivating storylines and analysis.

Read about it: https://mentalhealthcommission.ca/catalyst/book-club-all-in-her-head/

Did You Know?

Jessica Ward-King is known as the Stigma Crusher and contributes frequently to The Catalyst through service stories that offer insights and tips. She shows how to be a good ally to transgender and nonbinary people in a political and social climate that can be downright hostile and dangerous.

Read: Rallying as an Ally: https://mentalhealthcommission.ca/catalyst/rallying-as-an-ally/

Naloxone kits can reverse an opioid overdose and should be easily accessible. It is not only those members of the population who live with substance use concerns who could owe their lives to naloxone; it is also people who live with chronic pain and take prescription pain medications – or someone who could get into that pain medication by accident. It is all of us who, in our daily lives, could come across other people who – for whatever reason – have overdosed on opioids.

Read: Kit in Hand: https://mentalhealthcommission.ca/catalyst/kit-in-hand/

Hip-hop therapy is a fusion of hip-hop, bibliotherapy, and music therapy. Toronto therapist Freda Bizimana, MSW, RSW, works with Black and racialized youth in conflict with the law at The Growth & Wellness Therapy Centre. She shared how challenging it is to reach Black youth, particularly those who have come to therapy because of their interaction with the justice system. “They don’t want to be there talking to a stranger,” she says. “Hip-hop gives us a bridge, a way to connect through something they love.” This article received a Canadian Online Publishing Awards nomination. The awards will be announced in February 2025.

Read Remix Your Therapy: https://mentalhealthcommission.ca/catalyst/remix-your-therapy/

Her Story and Her Story

A personal narrative offers particular insights into a life story. The Lived Experience section highlights these stories. In 2024, we met 26-year-old Gillian Corsiatto of Red Deer, Alta., a published author – her debut novel, Duck Light, asks the serious question: “How can one break free of societal expectations?” – and more books and plays are underway. She’s also been a keen improv performer with Bullskit Comedy. She has three part-time jobs: She is a community educator and youth group leader for the Red Deer branch of the Schizophrenia Society of Alberta and has been a guest speaker for The Mental Health Commission of Canada’s Headstrong youth program; she manages social media and recruitment for the Red Deer Royals marching band (in which she used to play the tuba); and has taken a job wrapping and packaging caramels for a small, home-based business. If you have never met a person who lives with schizophrenia – you just did.

Read: What is It Like Living with Schizophrenia?: https://mentalhealthcommission.ca/catalyst/what-is-it-like-living-with-schizophrenia/

Meanwhile, Jessica Ward-King, who you know as the Stigma Crusher, frequently shares her personal stories, in addition to writing educational articles. In Yes, Me, the mental health advocate – who has a doctorate in psychology and first-hand knowledge of bipolar disorder – explains why her mental illness has classified Ward-King as a person with a disability under the employment equity act.

Read: Yes, Me: https://mentalhealthcommission.ca/catalyst/yes-me/

Watch for more great stories in 2025 – you can receive them directly in your inbox once a month by subscribing here: Catalyst Sign-Up – Mental Health Commission of Canada

Fateema Sayani edits The Catalyst and contributes frequently to the Representations and Book Club sections.

Fateema Sayani edits The Catalyst and contributes frequently to the Representations and Book Club sections.