Related Articles

Are you reading this in the bathroom? You wouldn’t be the first.

Digital culture has invaded intimate parts of our lives – bedrooms, dinner tables – and in those formerly stolen moments like the line at the grocery store or, dangerously, sneaking a glance while driving.

Those notes, texts, scrolls, and posts add up until it becomes a habit – and that becomes the stuff of your life. Your mental space is crowded.

Increasingly, I hear friends and strangers say they want their brains back. They’re looking for meaningful ways to do that – a new hands-on hobby like the piano – or they’re installing concentration apps.

Thinking in Facebook posts

I remember reading a think-piece where the author talked about missing important life moments, such as observing a toddler’s first steps, and how his brain was already focused on filming it or even mentally drafting a tweet about it. I’ve caught myself doing something similar and missing the beauty of the moment. It’s insidious. Suddenly we think more about performing our lives over living them.

So, what can we do? Johann Hari’s book Stolen Focus: Why You Can’t Pay Attention (2022) notes that simplistic solutions like, “just don’t touch your phone” don’t reflect the realities of how these devices are engineered.

They are designed to release dopamine making us spend way more time than we intended to, says Sophie H. Janicke-Bowles, a media psychologist and associate professor at Chapman University in California, in Psychology Today. Janicke-Bowles says, we need to know what “healthy” tech use actually looks like to foster it.

Technology differs in each of our lives

That’s why we’ve called this piece “design your digital diet.” It reflects the differing natures and needs of our technology use. Yes, we know – we’re online telling you to go away from the screen. However, is that not the challenge of our times? A digital diet means different things to different people. For example, a colleague uses the saying “sunshine before screen time,” to start and set the tone for the day. It works for her.

Making plans, ordering food, requesting a lift, looking for a date, finding a new shirt, or applying for a job requires interaction with a screen. It also taxes our mentality, time, focus, sense of self, and relationships.

To be sure, there are positive aspects. At the Mental Health Commission of Canada, we develop, promote, and encourage the use of quality, safe, culturally appropriate electronic mental health tools to bridge gaps in the healthcare system. Instant mental health care in your pocket. That’s a plus.

All to say, we can’t stop technology, but we can advocate for more control in the way it’s used so that we don’t ruin our capacity to pay attention.

Pay attention to your friends

The watering hole in my neighbourhood has a “pay attention to your friends” sign on the wall and printed on the menu. It’s part scolding and part invitation to disengage and reengage in a lost art – eye contact and conversation. The place is moody, low lit, and has great service – that should be enough to take us away from the vortex of our phones, yet it’s not. This nudge is kind of like holding up a mirror – um, duh, when did this phone thing become so normalized? If we need to be reminded, then it’s hard to wonder why we have a loneliness epidemic. I try to frequent that place. Elsewhere, it feels like everyone is always looking down, more engrossed in screens than in other humans’ expressions.

Surgeon says

When the U.S. surgeon general weighs in, you know stuff is serious. In June 2024, Dr. Vivek H. Murthy called for health warning labels on social media to address youth mental health issues. An advisory is reserved for significant public health challenges that require the nation’s immediate awareness and action – though, I’d argue it’s not confined to America, social media crosses borders.

The advisory notes that because adolescence is a vulnerable period of brain development, social media exposure during this period warrants additional scrutiny. Extreme, inappropriate, and harmful content continues to be widely accessible by children and adolescents, it notes, while underscoring the fact that social media also provides positive interactions and social support, especially for youth who are marginalized, including racial, ethnic, sexual, and gender minorities.

It notes that researchers believe that social media exposure can overstimulate the reward centre in the brain and, when stimulation becomes excessive, can trigger pathways comparable to substance use or gambling.

The features that keep us hooked are burrowing our brains: push notifications, autoplay, infinite scroll, likes and hearts, and algorithms that continually serve us the things we want. Ding! Ping!

Feel it

This technological invasion can manifest in strong responses: periods of complete disconnection or an engagement with more haptic elements – hands-on woodworking, say, or a new vinyl collection. For many, it’s also about re-engaging with in-person experiences like live theatre or concerts.

I like those shows where phones are banned. An early 2024 Trevor Noah comedy gig made me feel really present. I observed the design details of the old theatre, people’s reactions, the stage set up, and the issues being dissected through trenchant comedic bits. It took a security-endorsed phone ban to feel that good.

There was relief in taking in the experience unmitigated by a sea of small screens and feeling that collectivity. I admit wanting to steal a snap for my feed or personal memories. I also remember the olden days when we simply bought the t-shirt to say, ‘I was there.’

This is a generational bridge. Ensconced in a Gen X frame of reference, I straddle virtual and offline worlds. I know what it is to have made a call on a dial phone using a number I memorized – sometimes from a phone booth. I write in cursive, mail letters on paper, handled and paid in cash, read newspapers, found a location on a paper map, a phone number in the phone book, looked up something on microfiche, made mixed tapes as a form of flirtation and social currency, and took photos on film and had to wait until they came back from the camera shop – or 1-hour photo for the impatient – to see how they turned out. I often wonder about the different experiences of digital natives.

Another longing from an older era would be the craft of storytelling – whether it be oral histories or the written word – to convey meaning or share personal narratives. The essay The Crisis of Narration by Byung-Chul Han traces the change in storytelling. Once a communal bond over campfires that connected us to our pasts and provided a picture of the future, now those settings have been replaced by screens. The author calls this a transition to storyselling, a distinction that removes the artfulness and puts our personal lives into a commercial frame, which is, in essence, what we are doing. Like the saying goes, in social media, you are the product.

Ultimately, our relationship with technology is personal. We have to design our digital diet to reflect our realities, values, and needs – and consider the way it can enrich our lives. Mindful choices and intentional pauses can mitigate some of the nefarious effects of technology to support our mental well-being.

Log in, share your ideas for better digital engagement, and then log out for another activity. Books, friends, outings, or a digital pause. We’re crowdsourcing ideas on maintaining a balance. What do you do? Tell us on social media or via email: mhcc@mentalhealthcommission.ca. (We aren’t accepting postcard submissions, but we probably should).

Further reading: Tech Support: Online mental health support is breaking down barriers. We look at the potential of artificial intelligence and strategies for avoiding pitfalls.

Fateema Sayani

Fateema Sayani has worked in social purpose organizations and newsrooms for twenty-plus years, managing teams, strategy, research, fundraising, communications, and policy. Her work has been published in magazines and newspapers across Canada, focusing on social issues, policy, pop culture, and the Canadian music scene. She was a longtime columnist at the Ottawa Citizen and a senior editor and writer at Ottawa Magazine. She has been a juror for the Polaris Music Prize and the East Coast Music Awards and volunteers with global music presenting organization Axé WorldFest and the Canadian Advocacy Network. She holds a bachelor’s degree in journalism, a master’s degree in philanthropy and nonprofit leadership, and certificates in French-language writing from McGill and public policy development from the Max Bell Foundation Public Policy Training Institute. She researches nonprofit news models to support the development of this work in Canada and to shift narratives about underrepresented communities. Her work in publishing earned her numerous accolades for social justice reporting, including multiple Canadian Online Publishing Awards and the Joan Gullen Award for Media Excellence.

Related Articles

This is a story for any day of the year – but we want to note the 2024 theme for International Overdose Awareness Day – held annually on August 31 – which is “Together We Can.” The topic highlights the power of communities standing together to end overdose.

I have a kit that reverses opioid overdose, and I am not ashamed.

It is not only those members of the population who live with substance use concerns who could owe their lives to naloxone; it is also people who live with chronic pain and take prescription pain medications – like my wife. Or people like my son who could get into that pain medication by accident. It is all of us who, in our daily lives, could come across other people who – for whatever reason – have overdosed on opioids.

This can happen anywhere – including in the workplace.

In 2021, there were 2,129 cases of opioid poisoning out of 1.7 million workers in Ontario, according to Ontario Health. Tradespeople, service industry professionals, healthcare, and office employees – all workers – along with customers and contractors that enter businesses can be affected. With such a wide reach, it makes sense that a workplace first aid kit would contain a naloxone kit.

“To me it’s a no-brainer,” says Stephanie Fizzard, a former harm reduction worker. “When you’re grabbing your first aid kit, you’re grabbing your defib[rillator], and you want to be prepared with everything you need to handle that situation.”

Making naloxone part of our workplace first aid kits should be standard – along with training on how to administer it.

About opioids

Opioids like fentanyl, oxycodone, heroin, and morphine, are drugs with pain-relieving properties that can induce euphoria and have significant potential for addiction. They can be prescribed medications, or they can be obtained or produced illegally. According to the Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse, synthetic opioids are fueling the opioid crisis. Fentanyl and fentanyl-like substances that are of non-pharmaceutical origin and are illegally manufactured are the most widely available opioids in Canada’s unregulated drug supply. These drugs increase the risk of drug toxicity deaths because they are extremely potent and can be fatal, even in small amounts. Often, unrelated classes of illegally manufactured drugs contain fentanyl in an effort to increase addiction potential, leading to opioid overdoses even in people who did not knowingly use opioids.

What an overdose might look like

Opioids can cause an overdose and symptoms may present as difficulty walking, talking, or staying awake. It may show up as:

- Blue or grey lips or nails

- Very small pupils

- Cold and clammy skin

- Dizziness and confusion

- Extreme drowsiness

- Choking, gurgling, or snoring sounds

- Slow, weak, or no breathing

- Inability to wake up, even when shaken or shouted at

How naloxone works

Naloxone is a medicine that blocks the effects of opioids – that’s why it’s known as an “opioid antagonist.” When opioids enter the body, they rapidly bind with opioid receptors. Naloxone blocks the effects of opioids by kicking the opioids off those receptors – and binding to those receptors itself.

Naloxone is not a treatment for opioid use disorder. It is used to temporarily reverse the effects of opioid overdoses. It can restore breathing within two-to-five minutes and is active in the body for 20-90 minutes, whereas the effects of most opioids last longer. In other words, the effects of naloxone are likely to wear off before the opioids are gone from the body, which causes breathing to stop again. Naloxone can be administered multiple times as needed until help arrives. If naloxone is administered to someone who is not overdosing on opioids there will be no ill effects. So, naloxone is a low-risk, high-yield treatment.

The effects of stigma

I remember the first time I was given a naloxone kit. I had surgery in 2018 and needed a course of narcotic pain medication. I practically threw the kit back on the counter. “I’m not a drug addict,” I spat back at the pharmacist. I was concerned about how I would be seen and resistant to the idea that a person like me could even need naloxone. I know much more now – that opioids can affect anyone of any walk of life. The stigma that surrounds substance use can spill over into the use of naloxone.

“A lot of people feel like they’re enabling substance use if they reverse an overdose,” says Fizzard, who is also a person with lived experience of substance use. “I tell them ‘You’re helping people breathe and stay alive – you’re not doing anything else; you’re not helping them take drugs.’”

Fizzard notes that public services have not kept pace with issues of opioid use and overdose, meaning there aren’t enough services out there to meet needs. She makes the case for everyone having awareness of and access to a naloxone kit – noting that the largest barrier to using naloxone is not administering the medication, but the stigma surrounding its use, including in the workplace.

How naloxone is administered

Naloxone comes in two forms: injectable and nasal spray. The injectable form can be intimidating if you are not accustomed to needles. The nasal spray is quick and easy, according to Fizzard.

“The nasal is much more user-friendly,” she says. “In a pinch, you just pull it out of the packaging, put it in the person’s nostril and push the button. Simple. There’s no way of messing it up.”

Naloxone at work

Naloxone is not mandated in the workplace across Canada. Ontario has laws, embedded in the Occupational Health and Safety Act, requiring businesses that employ people who are at risk of overdosing to keep naloxone on hand and train staff how to use it. However, this is only a partial mandate, as those businesses who determine that they do not “employ people at risk” are not required to provide naloxone at work.

In British Columbia, naloxone is not required in the workplace, but tools exist to help identify where it should be employed. In Alberta, employers can choose whether or not to authorize the use of naloxone in the workplace, but if they do then the employer and worker must comply with a set of requirements established by the government.

For workplaces in Canada, health and safety mandates are the jurisdiction of the provinces and territories, meaning that a Canada-wide mandate is not likely. Instead, provinces and territories will have to decide to overcome the stigma and challenges and legislate the inclusion of naloxone in the workplace individually.

Are there barriers to keeping naloxone in a kit at work? It has a shelf life of around two years (or until used) after which it would need to be replaced and repurchased at around $100 per kit; this could pose a challenge to some businesses. (Ontario is providing kits free to businesses, for a limited time, to ease this burden). There could be training costs and stigma is an additional barrier that may prevent workplaces from acquiring naloxone kits.

Your kit

For individuals, naloxone is free in many provinces and territories and is available at pharmacies over the counter, or by ordering online, without a prescription. Online tutorials demonstrate how to use the kits.

As workers, we can inquire whether a naloxone kit is available at work and, if not, whether a kit and training could be made available. Naloxone kits are small, easily stashed in any workplace, and take minimal training to use. In Ontario, it should be enough to identify oneself as a person at risk of overdosing to trigger the requirement that a kit be provided.

In sum, it’s simple: naloxone can save lives – but only if it is available and people are trained how to use it.

Infographic: Do Drugs Contain What We Think They Contain? (Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction)

Further reading: How compassionate health care can alter the trajectories of people who use substances.

The author at the office with her workplace naloxone kit.

Jessica Ward-King

BSc, PhD, aka the StigmaCrusher, is a mental health advocate and keynote speaker with a rare blend of academic expertise and lived experience. Equipped with a doctorate in experimental psychology and firsthand knowledge of bipolar disorder, she’s both heavily educated and, as she likes to say, heavily medicated. Crazy smart, she’s been crushing mental health stigma since 2010.

Related Articles

It is midnight where you are, and you need immediate mental health support – but there are no services open. You find an app that offers culturally adapted peer-supported services from those trained in mental health – and you access the support you need.

You are a parent of a young child with little time and would like to access mental health support and counselling. You are able to log in online to an e-mental health session once you have put your child to bed and can get the support you need.

You have newly arrived in Canada from a country that views mental health support negatively and the stigma you feel is preventing you from accessing in-person care. You see that there is an online e-mental health service available where you can maintain your anonymity and you are able to access the mental health support that you need.

Mind the gap

These are just a few of the stories I hear as the manager of e-mental health at the Mental Health Commission of Canada. I lead a team that works closely with experts in Canada and around the world, including those with lived and living experience. Together, we collaborate to develop resources, frameworks, and supports around best-practices for those implementing e-mental health solutions in Canada. We work to demystify technology and focus on how quality e-mental health services have the potential to increase access to mental health services for those living in Canada. Increasing the quality of e-mental health support can also increase trust in these services. This means that people living in Canada have the flexibility to choose safe and effective care, when, where, and how they want.

We have witnessed many stories where gaps to accessing health care were bridged by technology.

Consider someone seeking support for an eating disorder, who doesn’t know where to go for help, or may not have services in their area. A service such as Body Peace Canada – a free, online source for those seeking support with eating disorders – provides access to resources and support.

The robots are coming

Maureen Abbott, right, with colleague Sapna Wadhawan, program manager at the MHCC, at a recent presentation of the MHCC Mental Health App Assessment Framework.

The term artificial intelligence (AI) may make some people uncomfortable or bring to mind visions of dubious robots. Hesitation and healthy skepticism are valid stances. With fast-moving technology comes big questions, along with big shifts that can improve access to quality care.

AI is being used in many ways to improve mental health care, from improving user experience navigating online systems, to saving time for practitioners by helping them to develop themes from their notes and connecting them to electronic health records.

The Mental Health Commission of Canada collaborated with CADTH – the Canadian Agency For Drugs And Technologies In Health – to develop reports on the uses and trends of AI in mental health. With the pending Bill C-27, aimed at enhancing consumer privacy, regulating AI, and updating data protection laws, those looking at safety with AI and mental health should be considering potential bias in the programming: think over- or underdiagnosing certain populations based on race or gender and how a reliance on existing data can replicate those harms. Or missing the mark by developing culturally insensitive material because it was not developed in consultation with the end users.

It is essential to involve clinicians and people with lived and living experience in the development and testing along with taking a human-centered approach to user design and testing. This means assuring that the privacy statement is clear, letting the end user know when they are interacting with a bot rather than a real person, indicate how their personal information is being used, and if it will be stored and shared – and if so, the details around that data use. Implementing best practices around data and privacy and promoting this to the general public will help to ensure trust among users and a broader uptake.

This focus on safety and best practices for AI use in mental health care is one of the recommendations being brought forward in the E-Mental Health Strategy for Canada, which will be released at the E-Mental Health International Collaborative (eMHIC) Digital Health International Congress September 19-20, 2024 in Ottawa. Developed with those with lived experience, policy makers, practitioners, and health leaders, the strategy will highlight six key priorities and 12 recommendations for e-mental health in Canada.

It’s important to have standards

When integrated properly and into mental health care delivery, e-mental health is just as effective as face-to-face services, and the technology is improving every day. Not only will this result in more people getting help faster, but it can also reduce the personal costs of accessing services and the costs of organizations accrue in implementing mental health services.

Some people may feel most comfortable accessing mental health services in an in-person environment, while others may choose an app or another e-mental health solution (such as online therapy) to access mental health services. The important part is for those living in Canada to have the opportunity to choose the types of services that work for them and that those mental health services are of a high-quality: safe, accessible, effective, and culturally adapted.

The e-mental Health team at the Mental Health Commission of Canada has been working to ensure the best practices are in place when implementing e-mental health services.

How? One example is the MHCC Mental Health App Assessment Framework. These national standards are meant to improve the quality of apps for people living in Canada. Before its publication, access to safe, secure, and effective mental health apps was largely undefined in Canada. The framework was developed with 200 collaborators in Canada and internationally, including those with lived and living experience, policy makers, government officials, app developers and designers, academic researchers, and mental health service providers to develop the framework.

The Cultural Safety, Social Responsibility and Equity standard within the framework includes content on Indigenous data security and privacy, gender equity, and representation from racialized communities. This framework is currently being used to assess a range of mental health apps in different provinces in Canada that are new or already widely adopted.

Al Raimundo was on the core development team for the framework and is a person with lived experience and an app developer. Raimundo says, the framework provides guidance for a range of products, even those that may not be immediately appealing to clinicians.

“Even if there’s something the professionals don’t love about an app, if people love them, then we should understand why. If a bunch of people are using it, something’s drawing them,” Raimundo says.

To help expand and better understand e-mental health services, the Mental Health Commission of Canada developed the E-Mental Health Implementation Learning Modules in collaboration with the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH). The online learning modules are free, self-directed, and designed to give mental health providers, managers, leaders, and students the knowledge and skills they need to integrate e-mental health into their daily practice, and support effective, person-centered e-mental health service delivery.

Electronic mental health options are coming online quickly, and helpful standards and frameworks are being developed in tandem to bridge gaps between quality, demand and access.

The rapid advancement of e-mental health technologies offers immense potential to improve access to care. By prioritizing safety, quality, and cultural sensitivity, we can create a robust and reliable mental health support system that meets the needs of people in Canada.

Resources: Find a number of resources on the MHCC E-Mental Health page.

Guide: Where to Get Care – A Guide to Navigating Public and Private Mental Health Services in Canada

Maureen Abbott

A Masters-educated Manager and Certified Health Executive (Canadian College of Health Leaders) on the Innovation team at the Mental Health Commission of Canada (MHCC). Her work focusses on e-mental health, including the standardization of e-mental health apps in Canada, e-mental health implementation, artificial intelligence and mental health, an e-mental health strategy for Canada, strategic partnerships and stakeholder engagement, and knowledge exchange. Maureen is the Chair of the MHCC’s E-Mental Health Collaborative and a CHIEF Executive member with Digital Health Canada.

Subscribe to Catalyst

Subscribe to get our magazine delivered right to your inbox

Related Articles

Hands down, Rachel Kingston’s biggest parenting challenge is trying to manage her 13-year-old daughter’s social media use.

“My daughter was diagnosed with general anxiety disorder last year,” Kingston (a pseudonym to protect her family’s privacy) explains, “and I think some of her chronic anxiety is tied back to social media. Unlike some families, we haven’t had to deal with body image issues or being bullied, but I really worry about the lack of down time and true rest she gets.”

Kingston, a Calgary mother of two, says that her daughter’s social media use became a problem during the lockdown, when it represented the only form of social life available. It hasn’t tapered off since, though, and Kingston worries about the impact it might have on her nervous system. If it were entirely up to her daughter, there’d always be a YouTube or TikTok video playing in the background, no matter the activity—baking, drawing or even having dinner.

“If we put on a show to watch as a family, I look over and see she’s also on Snapchat,” Kingston says. “The kids don’t really care about my concerns.”

We know, for sure, that Kingston isn’t alone. Aside from casual banter about wresting kids away from screens in parent circles, five school boards in Canada are taking legal action against social media juggernauts that own Snapchat, TikTok, Facebook, and Instagram.

Neinstein LLP, the Toronto law firm that represents the school boards, has claimed (in a written statement) that social media products are “intentionally designed for compulsive use,” and the “addictive properties of these products have compromised students’ ability to learn, disrupted classrooms and created a student population that suffers from increasing mental health harms.”

Conversation starter

The lawsuits, as well as the even more recent proposal to crack down on problematic smartphone use in Ontario’s schools, have provoked a lot of conversation. Not everyone thinks measures like these are warranted, especially the young people in question, some of whom feel their freedoms are being curtailed.

One CBC Toronto story found several East York Collegiate students didn’t support the lawsuits. One student said if she was still doing well in school, she couldn’t see how it was affecting her negatively. Another said he didn’t want to be told whether of not to use social media and argued that it was up to him to choose. He went on to say that teachers should try taking phones away instead of suing a company. A little over a month later, the provincial government did just that, when it announced a partial ban on smartphones in schools. That policy is roughly in line, incidentally with UNESCO recommendations, which last year, advocated for school smartphone bans, arguing that they were distracting and bad for students’ mental health and well-being.

There’s a mounting pile of evidence to back this up. Jonathan Haidt, author of the new book, The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness, was moved to write on the topic when he discovered a “surge” of mental illness diagnoses in the undergraduate population of the United States. Between the years 2012 and 2019—roughly the period in which smartphone ownership became ubiquitous—anxiety and depression rates more than doubled (by 134 percent and 106 percent, respectively).

This evidence, of course, is based on correlation—not iron-clad causation. That said, neuroscientists have been working on figuring out the mechanisms that might make children more susceptible to problematic social media use, as well as more likely to experience negative mental health impacts.

This is your brain on social media

“The pre-frontal cortex, which is the part of the brain that tells you, ‘I should put this device down now’ develops much later and children are really lacking that ability,” says Emma Duerden, Canada Research Chair in Neuroscience and Learning Disorders and Assistant Professor at Western University in the Faculty of Education.

Having trouble controlling impulses and not knowing when to put a device down is only one piece of the problem. Another factor has to do with the fact that children learn a lot through rewards-based learning, which makes them particularly susceptible to compulsive use.

“With children, you can see behaviour change very quickly if you offer them a candy or a cookie to get them to do something they don’t want to do,” Duerden continues “Children’s brains are hard-wired to respond to rewards and social media really acts on that system, because it’s designed to be highly rewarding with all the likes, comments and notifications.”

She notes that exposure to stressful images at a young age is a well-characterized pathway to serious mental health issues in late childhood.

“Content is basically completely unregulated in social media,” says Duerden. “Television, movies and even video games have to undergo some sort of examination from regulatory bodies.”

Although his focus is on children at present, Jonathan Haidt’s research into adolescent mental illness grew out of his work on the role smartphones have played in amplifying the “long-known weaknesses of democracy.” Although harder to measure than mental health diagnoses, as everyone knows who talks about living in the “stupidest timeline,” political dysfunction is clearly on the rise as well.

“I would say that social media and, more generally, devices, have been an accelerant of the erosion of civil discourse on campus,” says Professor Randy Boyagoda, University of Toronto’s first adviser on civil discourse.

Boyagoda notes that because we use our devices so much, it’s become hard to see how important it is to have in-person interactions.

“I would say that the near permanent mediation of our lives by our devices has made it difficult especially, I think, for students, and in a different way, for faculty, to understand the irreducible importance of embodied face-to-face encounters,” he explains. “We would rather turn to our devices – as either mediums or as shields, frankly – from that type of encounter.”

Boyagoda says that, in his experience, discourse in both classes and faculty meetings was less constructive, more pointed, and more critical when they moved online during the pandemic than when they were held in person.

“You may still have pointed or critical comments, but they are received in a different way because, again, of the unembodied account,” he adds. “I can see the person’s body language and they can see mine. They can hear my tone. I can see their tone. I can tell when someone in a room isn’t fully with me on a point, and I want to understand why. All of that is only possible in person.”

Not going anywhere soon

None of this is to say that the erosion of mental health and civil discourse is monocausal. Or, for that matter, that all young people will react to social media in the same way. University of British Columbia professor of psychology Amori Mikami advises we need to approach social media as merely another form of communication that we figure out how to use it so that it serves us, as opposed to the other way around.

“I feel there’s a lot of talk and discussion about the negatives about social media and how it can harm mental health,” says Mikami. “And let me be clear, I think it can. But I don’t believe it’s an inevitability and I think there are ways in which it can benefit mental health too.”

Mikami feels a lot of problems stem from people who use social media as a passive consumer and just “ride the social media wave” to see where it takes you. “You need to ask questions like, ‘What am I getting out of this interaction?’ ‘What is the benefit?’ and ‘How do I feel afterwards?’ so you can make informed choices about what social media to engage with or when to engage.”

Social media, everyone agrees, isn’t going anywhere. But we need to find ways to use it appropriately that go beyond advice to turn off notifications and change our smartphones’ display screen from colour to greyscale (although these are both very effective).

In The Anxious Generation, Jonathan Haidt prescribes collective action on a number of fronts, including encouraging children to engage in play and immersion in real-world communities in meaningful ways. And, for the sake of civil discourse, this can’t end when we graduate from high school.

“We need a demonstration, to faculty and students both, that there is something irreducibly good about the act of thinking out loud with someone else,” says the U of T’s Boyagoda. “And that can best be done, hands-free, you know, without a device involved.”

He continues: “We need to recognize and reckon with disagreement and difference and see these as good things, insofar as they can lead to mutual understandings and increased shared understandings of a common issue, and ideally contribute to the common good.

“And to the pursuit of truth.”

Further reading: Is E-Mental Health Support Right for You?

Resource: #ChatSafe: A Young Person’s Guide to Communicating Safely Online About Self-Harm and Suicide.

Subscribe to Catalyst

Subscribe to get our magazine delivered right to your inbox

Related Articles

At 26, Gillian Corsiatto of Red Deer, Alta., is a published author – her debut novel, Duck Light, asks the serious question: “How can one break free of societal expectations?” More books and plays are underway. She’s also been a keen improv performer with Bullskit Comedy.

Gillian Corsiatto

She has three part-time jobs: She is a community educator and youth group leader for the Red Deer branch of the Schizophrenia Society of Alberta and has been a guest speaker for The Mental Health Commission of Canada’s Headstrong youth program; she manages social media and recruitment for the Red Deer Royals marching band (in which she used to play the tuba); and most recently, she has taken a job wrapping and packaging caramels for a small, home-based business.

It sounds like a busy life, but Corsiatto understands the importance of managing stress. “It’s not like 9 to 5. I make sure I have enough time to rest and enough time for myself at home,” she says.

If you have never met a person who lives with schizophrenia – you just did.

Corsiatto is among more than 147,500 Canadians who deal with schizophrenia, a severe mental illness.

New standards

To ensure those living with the condition experience better outcomes and have the kind of hope for the future that Corsiatto does, The Mental Health Commission of Canada, in partnership with Ontario Shores Centre for Health Sciences, has released the Schizophrenia Quality Standards National Demonstration Project, a synthesis of the best medical evidence, with four demonstration health sites across Canada: Adult Forensic Mental Health Services, Manitoba; Hotel-Dieu Grace Health Care and Canadian Mental Health Association, Windsor, Ont.; Newfoundland and Labrador Health Services; and, Seven Oaks Tertiary, B.C. Health practitioners will receive education and training on best practices in therapy and medication treatments and helping patients and their families cope with the illness over the long term.

This will come as a welcome relief to many. The symptoms of schizophrenia tend to arise in adolescence or young adulthood, as they did for Corsiatto, who says she was about 13 when she first experienced delusions.

Early symptoms

“I thought I saw dead people,” she says. “I found it very hard to pay attention in school, and socially I was not really fitting in with the other kids because of my odd behaviour and the things I would talk about. That’s when I started hallucinating. I was very much in my own world at that point.” Corsiatto says she also engaged in self-harm to relieve her psychological turmoil.

Overcoming her psychosis and other symptoms wasn’t easy. At 14, she spent time in a psychiatric ward, where she received medication and was monitored for improvement in her symptoms. This helped eventually, she says, but the medication had side effects. “I was so tired all the time. And there was hunger. I ended up gaining a lot of weight.” She also remembers that some caregivers had the attitude that their patients needed to be disciplined and corrected.

“We were treated as though we were bad kids, not sick kids. Like it was all behaviour problems, causing trouble. I’m an adult now and can stand up for myself, but I wish I would have said something or stood up because I really felt like I wasn’t being treated very well.”

Corsiatto’s symptoms did improve significantly though, with therapy and medication. Throughout most of high school, she did not have hallucinations and was able to manage her studies and extra-curricular activities. She even went off her medication for a time, but that did not last. After graduating high school, she went to Red Deer College (now Polytechnic), majoring in music. “School was stressful. I didn’t complete the program,” she says. Along with medication she had previously been given for anxiety, she resumed taking medication for psychosis. This was a hard period, says Corsiatto. “I just coped with it.”

The next chapter

Gradually, though, the medication and therapy again helped and for the past four years, Corsiatto has been able to build a life she enjoys, with a desire to help other young people with severe mental illness and a lot of hope for the future. “I really want to make writing a career,” she says, as she works on the sequel to Duck Light.

“I know that there’s hope for the future, and I know that I will always deal with this illness and this schizophrenia, but I also know that I can manage it, and I am more than my schizophrenia, and if things do get bad, I know what to do about it.”

For example, she says hallucinations and delusions are still something she experiences, “but to a much lesser extent than I used to,” Corsiatto says. “Several factors impact whether or not I recognize them as such. Medication is definitely a big part, but I also credit life experience. I have learned to gauge the reactions of others or, if I’m with someone I trust, asking them what they are experiencing in that moment. If I am out in public and experiencing a hallucination and no one else around me seems to notice or react to it, that’s a good indicator to me that it’s a hallucination. Things that will make it harder to decipher whether real or not are stress, lack of sleep, or if I am alone.”

She sees ways the mental health system can improve its treatment of young people with schizophrenia, and notes that a significant number of people with mental illness also struggle with substance use issues, finding suitable housing, and waiting lists for treatment. “It’s case by case. I’m on a waiting list for an autism assessment, but I feel that if I go to the hospital, I can get help pretty fast. If I need an emergency appointment with my psychiatrist, I can do that.”

Individual experiences

Corsiatto wants people to know that no two people with schizophrenia experience it the same way. If you want to know what someone is going through, “talk to the individual, don’t generalize,” she says.

For young people going through treatment for schizophrenia, she says, “It’s not all about the medications and the illness. It’s really important to focus on what makes you happy. What do you like to do? What are you proud of? What would you like to achieve?”

Answering these questions for herself has made Corsiatto feel like she’s “living the dream.”

Each time she speaks publicly, she feels she’s dispelling misconceptions. “I love changing people’s mindsets about what they think schizophrenia is. ‘This is how someone with schizophrenia is going to act.’ And then I show up. And they think this person is pretty normal. So, I love that. And changing the way people think about interacting with schizophrenia and people with schizophrenia. They can just talk to me like I’m a normal person – because I am.”

Resource: Where to Get Care – A Guide to Navigating Public and Private Mental Health Services in Canada.

Resource: Addressing stigma in health care.

Moira Farr

An award-winning journalist, author, and instructor, with degrees from Ryerson and the University of Toronto. Her writing has appeared in The Walrus, Canadian Geographic, Chatelaine, The Globe and Mail and more, covering topics like the environment, mental health, and gender issues. When she’s not teaching or editing, Moira freelances as a writer, having also served as a faculty editor in the Literary Journalism Program at The Banff Centre for the Arts.

Subscribe to Catalyst

Subscribe to get our magazine delivered right to your inbox

Related Articles

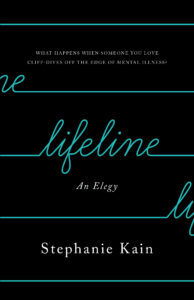

What happens when someone you love cliff-dives off the edge of mental illness?

This question appears on the cover of Stephanie Kain’s novel-memoir Lifeline: An Elegy (ECW Press, October 2023). Kain answers that and other questions over 210 pages of prose, text exchanges, short stories, and essays.

The book is stunning in its fragmented format, befitting the author’s experience of grappling with a frayed healthcare system, one’s own perspectives and biases, the mental illness of a loved one, and daily life challenges during the emergency phase of the pandemic.

The book is stunning in its fragmented format, befitting the author’s experience of grappling with a frayed healthcare system, one’s own perspectives and biases, the mental illness of a loved one, and daily life challenges during the emergency phase of the pandemic.

Complicated romantic, platonic, and familial relationship dynamics are named and noted with dry wit and underscored with pop culture references and lyrics (Shawn Mendes, Sara Bareilles, and Mumford & Sons, among them).

In Lifeline, advocating for one’s care is “Shirley MacLaine-ing” in a reference to Terms of Endearment. In a notable scene from that film, you hear a frustrated bellowing of, “It’s after 10!” as MacLaine’s character nearly has a breakdown at the triage desk trying to get her daughter a pain shot. Her pleading eventually works, and the volume and tone suddenly change. “Thank you,” she tells the nurse just above a whisper.

Kain has similar moments of raw reality. The story centres around the author’s complicated relationship with a woman diagnosed with suicidal depression. Kain writes about the indignities of a locked ward, having to administer heavy medications, supporting someone through the after-effects of electro-convulsive therapy, and her own well-being. The author – a creative writing professor at the University of Ottawa – spends time in PEI, and the island figures prominently as she looks to find a way forward.

The book’s format is jaunty and compelling, and its portrayal of the frustrations and realities of helping a loved one through mental illness is done with intensity and honesty – yet free of judgement and stigma, the things that can hold people back from seeking care.

The insomnia is camped out permanently like an adult child moving home for quarantine, knowing you can’t kick it out, even if it’s on its worst behaviour.

A chapter called Eight Things I’m Putting in Your Care Package offers insight as the author rationalizes each choice.

Multicoloured Pens: Blue and black are depressing as f–k, and since you hate any pencil crayons that aren’t your top-of-the-line artist brand, I’m not even going to try sending you any. Instead, you can draw with multicoloured pens and stop judging yourself and your work because nobody expects drawings made with multicoloured pens to be good. They’re just supposed to pass the time.

You might not recall because #Depression, but the last time you were in there, you made something in art class and spent half an hour criticizing it before I finally screamed at you that you were in a psychiatric hospital and the art wasn’t supposed to be good for the love of f–k and maybe this was the problem!

In this way, the book made me think about portrayals of mental illness in contemporary fiction. The Mental Health Commission of Canada’s magazine, The Catalyst: Conversations on Mental Health, has a section dedicated to this topic called Representations. It takes on popular narratives of mental well-being to mark their shifts. If you’ve watched One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest or Thirteen Reasons Why, you can see there is room for improvement with regard to nuance, honest portrayals, and false notions.

I was inspired to start this feature after reading a series in The Walrus reflecting on problematic classic works. This re-examination brings to light the ways in which society and literature have changed. Author Myra Bloom looks at the darker side of Leonard Cohen through a re-examination of Beautiful Losers’ stereotypes with discussions on the genius myth and what historian Martin Jay calls the “aesthetic alibi” used to justify bad behaviour. Writing about The Unbearable Lightness of Being, Amanda Perry says, “At seventeen, I could still assume beautiful phrases were true ones and take characters as guides for living.” Perry reflects on “the male writers whose words have shaped my psyche and whether it’s time to shake them off.”

Stephanie Kain

Reading that sentence, I think of depictions of mental health that live in my psyche. I grew up listening to The Ramones, whose many titles send up mental wellness (“I Wanna Be Sedated,” “Go Mental,” “Mental Hell,” “I Wanna Be Well” – I made an entire playlist), as well as their live-in-your-head video for “Psycho Therapy.” I think about how Sylvia Plath, who, like all of us, was a product of her time. Re-reading The Bell Jar now makes me think about how it’s a case study in self-stigma and structural stigma. Terms we didn’t use then. We know more now.

Problematic depictions in the mass media won’t end – sensationalism and romanticization frequently propel narrative arcs – but the huge role that popular culture can play in the understanding and representation of mental health makes a book like Lifeline such a notable work in illustrating the story of living with and supporting someone with mental illness through ups and downs, contradictions, contours, and textures.

“Healing is not linear, darling,” the author writes—and the book’s format artfully follows that statement by jumping around in time as the author reflects and looks forward, trying to imagine a time when the person she cares for so deeply might be better.

Further reading: Breaking Stigmas, Saving Lives.

Fateema Sayani

Fateema Sayani has worked in social purpose organizations and newsrooms for twenty-plus years, managing teams, strategy, research, fundraising, communications, and policy. Her work has been published in magazines and newspapers across Canada, focusing on social issues, policy, pop culture, and the Canadian music scene. She was a longtime columnist at the Ottawa Citizen and a senior editor and writer at Ottawa Magazine. She has been a juror for the Polaris Music Prize and the East Coast Music Awards and volunteers with global music presenting organization Axé WorldFest and the Canadian Advocacy Network. She holds a bachelor’s degree in journalism, a master’s degree in philanthropy and nonprofit leadership, and certificates in French-language writing from McGill and public policy development from the Max Bell Foundation Public Policy Training Institute. She researches nonprofit news models to support the development of this work in Canada and to shift narratives about underrepresented communities. Her work in publishing earned her numerous accolades for social justice reporting, including multiple Canadian Online Publishing Awards and the Joan Gullen Award for Media Excellence.

Subscribe to Catalyst

Subscribe to get our magazine delivered right to your inbox

Related Articles

When you think of mental health, do you want to have a good laugh?

Humour is one of the most effective ways brands have to capture attention and be memorable. It’s not always easy, but if you can strike the right balance between tone and your target market’s funny bone, it’s gold.

Unfortunately, for most health brands, humour represents pitfalls. Fears of poor taste or making people feel minimized are real. This fear of funny means, for the most part, we are left tugging on heartstrings or seeking inspiration from the patient as brave soldier.

In fact, a few years ago, SickKids launched a brilliant campaign where they combined the two with children as gritty-eyed warriors fighting illness and injury. While there were critics of the VS Limits campaign, it did its job, surpassing the $1.5-billion goal.

When you are a mental health advocate, there is a lot on the line. With so much stigma associated with mental health, anything that might further confuse issues makes the use of humour thorny. Yet, if you are struggling with mental illness, you don’t always want to be immersed in the dark imagery that often accompanies stories of mental distress. Unfortunately, for a long time, mental health meant a series of images of people with their heads in their hands.

We contain multitudes

The reality is much more dynamic. Mental health discussions, even the toughest of them, can be about optimism, change, and recovery. We don’t have to go the warrior route. It is possible to go for and succeed with the holy grail of healthcare promotion: humour.

Ottawa Public Health has been a champion of that approach. When speaking to Kevin Parent, the social media lead, he noted that while the public health unit is often funny, they can get away with it because, first and foremost, they are always authentic. That means they express a variety of voices on their feed. Some are full of comedic relief; others are serious, sad, educational, and informative – essentially, the range of human emotions.

For example, during the pandemic, mask discussions lost all humour for me, and yet my inner sci-fi geek was tickled when they featured The Maskalorian with the quote, “This is the way.” It made a tiresome topic fresh and funny.

“We do everything we can to stay authentic,” Parent says. “If you understand your audience, if you take the time to know them, then you’ll know what they think is funny. You’ll also know when they need a laugh. It isn’t that a particular thing is right, and another is wrong; it’s more a case of what’s right – for right now.”

So, during the emergency phase of the pandemic, maybe mask-breath jokes were too soon – though, these days, most people would have experienced this and get the reference.

In recent years, constraints that have kept humour at bay in the health sector have fallen due to the popularity of social media influencers and the acknowledgement by health professionals that the voices of those with lived experiences are not only relevant but important in everything from research to recovery.

The shift in perspective was aptly demonstrated when that bastion of academic rigour, Harvard University, conducted best practice educational sessions with TikTok mental health influencers Rachel Havekost and Trey Tucker. The engagement brought better health information to the public through those popular feeds. However, it’s not always a successful partnership if the fit between knowledge and theatre isn’t right. No matter how well-intentioned or researched, if the content isn’t entertaining, it does not get viewed.

Some experts advise healthcare marketers entering the humour arena to be gentle. That’s not bad advice, but it does leave the content somewhat bland. When the Mental Health Commission of Canada decided to refresh a few years ago, it wanted to bring the brand into the light and occasionally tickle the funny bone. This meant banishing images that conjured deep unhappiness. You know them: a dark day and a sad person sitting alone on a bed, facing a corner. It’s usually in black and white to reinforce the glumness of the subject matter. If that wasn’t enough, there are also lots of clouds.

Silver linings

The change to optimistic imagery wasn’t simple. As many experts insisted, mental health isn’t always sunshine and daisies. The challenge is understanding what viewers are looking for so that good information can be digested.

I am not alone in saying nothing about dreary imagery draws me in and makes me want to learn, see, or hear more. If I also get served a lecture using technical language, I’m out. It’s not that dark and difficult times are never part of the mental health journey, but contributing to doom scrolling hardly seems progressive. Nor is it that viewers don’t want well-researched information, but anyone who has ever had a loss of mental health knows the process is not simple. There are good and bad times, sometimes in the same 24 hours. Regardless of where you are on the continuum, a little humour can go a long way. A good laugh can reduce stress and tension, provide relief from pain, improve your mood, and has a host of other well-documented impacts.

The issue is finding the right balance of information and entertainment. Infotainment is easy to say and hard to achieve. It’s fine to explain that laughter is the best medicine and cite a series of research studies, but putting humour into play while delivering information responsibly to an audience that often includes people at risk is difficult.

Mental health can be funny, but it can also be sad, scary, and complicated. For advocates, advertisers, and audiences, getting the balance right is not only essential, but it can also be life-altering.

Further reading: No more doom and gloom: How we’re using photography to inspire hope.

Resource: Fact Sheet: Common Mental Health Myths and Misconceptions.

Debra Yearwood

A communications pro with more than 20 years of executive experience in the health sector, expertly navigating everything from social marketing to crisis comms. When she’s not advising on the boards of Health Partners or Top Sixty Over Sixty, she’s busy finishing her book on thriving in later life (because why stop now?). Certified Health Executive by day, diversity advocate and magazine contributor by night—Debra’s the one you call when things need fixing or explaining.

Subscribe to Catalyst

Subscribe to get our magazine delivered right to your inbox

Related Articles

The sounds of sorrow and hope amid a tangle of words on injustice, racism, and brutality often define conscious rap music. Their presence is an acknowledgement of the challenges faced and a call to Black communities to stay strong despite the pressures of prejudice. Music’s role in expressing the internal, external, and seemingly eternal conflicts arising from oppression makes it an important player in the survival of Black culture, identity, and mental health.

Everyday racism activities that permeate daily life become ‘normalized’ in the mainstream despite stated commitments to equity. These transgressions often appear mindless or habitual and while they hurt, it’s sometimes easier to ignore than battle every incident. When I was a political assistant on Parliament Hill many years ago, small green buses would wind their way around the precinct, bringing staff and members to different buildings. Regularly, the buses would drive past me. The drivers would see me flagging them but never considered that a Black woman could be a Hill staffer, so they drove by. They passed by me so often that when they did stop, I was startled.

The loop

Freda Bizimana

Given their frequency, these racist moments are regularly treated as too minor to address. However, their cumulative impact reproduces social relations of power and oppression and, over time, damages the health and well-being of Black people and other people of colour. In effect, everyday racism creates systemic racism, and systemic racism creates the environments that allow everyday racism to thrive. They both produce challenges to mental health.

When violence against Black citizens is normalized or overlooked with little to no reaction from agencies such as the media or government, then it would be easy to allow despair or cynicism to take over. According to a 2018 study published in The Lancet, Black Americans report upwards of 14 poor mental health days for every reported police killing of an unarmed Black American in their state of residence.

There’s all sorts of trauma from drama that children see

Type of s–t that normally would call for therapy

But you know just how it go in our community

Keep that s–t inside it don’t matter how hard it be

– Lyrics, J. Cole, “Friends” 2018.

The impacts are multi-generational. Discrimination experienced by a parent may also negatively impact their child’s mental health, even if that child did not experience the discriminatory treatment firsthand. In the same Lancet study referenced above, the impacts of “indirect” or “vicarious” racism were found to worsen the progression of inflammatory disease, sleep disturbances, chronic health conditions, and cognitive function – all of which decay mental health.

Music has been and remains an important part of Black cultural expression. Its ability to communicate complex messages and emotions is integral to its construction. It was fear of the effectiveness that led U.S. legislators to ban slaves from using drums in 1739. Almost 150 years later, in 1988, NWA’s single, “F–k tha Police,” drew similar concerns from authorities when it was released.

It’s not surprising then that rap music and hip-hop culture play an important role in not just expressing the concerns, fears, opportunities, and hopes of contemporary Black people but also providing an outlet to improve mental health in those same communities. In 1998, researcher and clinician Dr. Edgar Tyson introduced hip-hop therapy at the 20th Annual Symposium of the Association for the Advancement of Social Work.

Mama had four kids, but she’s a lesbian

Had to pretend so long that she’s a thespian

Had to hide in the closet, so she medicate

Society shame and the pain was too much to take

– Lyrics, Jay-Z, “Smile,” 2017.

Hip-hop therapy is a fusion of hip-hop, bibliotherapy, and music therapy. Music therapy has established credentials that stretch back to research done by Zane Ragland and Maurice Apprey as early as 1974. Similarly, bibliotherapy, which focuses on the use of literature, such as stories and poetry, to facilitate treatment, is also well established and has been proven to be effective by several systematic reviews in the treatment of emotional, physical, and mental health problems among adults.

Tyson’s groundbreaking research is the cornerstone of contemporary hip-hop therapy and lends itself well to culturally appropriate care, particularly among young people.

Toronto therapist Freda Bizimana, MSW, RSW, works with Black and racialized youth in conflict with the law at The Growth & Wellness Therapy Centre. She shared how challenging it is to reach Black youth, particularly those who have come to therapy because of their interaction with the justice system. “They don’t want to be there talking to a stranger,” she says. “Hip-hop gives us a bridge, a way to connect through something they love. It’s a modality that is not rooted in European experience. It brings back the drums common to the African Black diaspora.”

New release

In her practice, Bizimana notes that clients are not often engaged and start with one-word answers. She’ll look at their headphones and ask them what they are listening to. They’ll share their favourite songs, then delve into lyrics. At some point, Bizimana will ask them, ‘Do you ever feel that way?’ Suddenly, they are having a conversation. “This modality eases them into the process,” she says.

How does Bizimana respond to critics who question the efficacy or appropriateness of this therapeutic approach? “Hip hop is a mirror of society. If you have a problem with it, you need to look at what’s happening in society,” she says. “How are we addressing anti-Black racism? What is happening within our school systems with Black youth? What are we doing to deal with police brutality? Why are young people numbing themselves?”

No need to lie into your emerald soul

You surely know gold is always in your throat

Why not let it shine?

You’re in control of the dream

– Lyrics, Kid Cudi, “The Commander,” 2016.

Rap can surf off strife and act as a vehicle of escape. Political commentary set to a 4/4 beat transforms frustration with structural racism into an accessible anthem of collective experience. Kendrick Lemar’s album, To Pimp a Butterfly, provides political commentary on faith, culture, and race. The song “Alright” pulled those insights together and made its way onto Pitchfork and Billboard best-of lists for 2015. Lamar notes in the poem that runs before and after the song that the conflict is based on discrimination and apartheid. Like the songs of slaves, he sings that with God, things will be alright. The widescale popularity and uplifting beat eventually led to its adoption by the Black Lives Matter movement, reinforcing the relationship between conscious rap and activism.

Collective efforts

Rap’s themes of overcoming obstacles and surviving life’s challenges are specific as well as inspirational. They reflect the realities of daily life for many in Black communities. Hip-hop therapy takes rap music and other elements of hip-hop culture and blends them to create a culturally relevant therapeutic offering. Unlike regular music therapy, it also embraces group therapy. This allows for shared experiences and reduces the feelings of isolation that are often the consequence of racism. The evidence shows that it can reduce depression and anxiety while also improving communication and emotional expression.

Hip-hop therapy also does something else; it empowers. Rap music varies widely and can reinforce doctrines of sexism, commercialism, and drug culture. For Black women, it can be another source of disrespect and denial. Through hip-hop therapy, women can counteract those influences through the creation of lyrics and discussions that tell their stories in their voices.

“Hip hop gives a voice to Black youth,” Bizimana says. “It allows them to have a space to express, heal, and grow with a medium that is familiar. I’d like to see it used more frequently in Canada,” she says, noting that more therapists are adopting this approach through individual and group sessions. She is seeing schools incorporating it into curricula. “Sometimes help can come in the form of a coping playlist,” she says, “like a playlist for when you are sad and another for when you need motivation.”

Years ago, if asked, I would have expressed my disdain for hip-hop culture. It often struck me as self-flagellation, and I could not see why so many young Black people, particularly women, were enamoured with it. However, when my son began to play conscious rap for me, and I listened to lyrics that reflected my own truths, I could not help but rethink my opinions. Now, in moments of doubt and struggle, when cultural norms have stifled my options or limited my view, I find the music uplifting. No small wonder I would be caught by the appeal of hip-hop therapy. It captures and formalizes what many of us in the Black community already know: music heals, and no music heals as well as our own.

Further Reading: Weaving Through the Challenges

Resource: Experiences with Suicide: African, Caribbean, and Black Communities in Canada

Debra Yearwood

A communications pro with more than 20 years of executive experience in the health sector, expertly navigating everything from social marketing to crisis comms. When she’s not advising on the boards of Health Partners or Top Sixty Over Sixty, she’s busy finishing her book on thriving in later life (because why stop now?). Certified Health Executive by day, diversity advocate and magazine contributor by night—Debra’s the one you call when things need fixing or explaining.

Illustrator: Holly Craib

Holly Craib explores the relationships between colour and light in her artwork. She won a 2023 Applied Arts award for a conceptual illustration series.

Related Articles

Ahead of the International Trans Day of Visibility – an annual event dedicated to supporting trans people and raising awareness of discrimination — the Stigma Crusher reflects on ways of showing up and showing support.

It’s easy to be a friend, a comforter, a confidant, a ramen pal, or a late-night horror flick ride-or-die – but that is not what it means to be an ally. So, how does one be an ally? And more to the point, how does one be a good ally to transgender and nonbinary communities in a political and social climate that can be downright hostile and dangerous?

An ally is a person, often cisgender (a person whose gender corresponds to the sex assigned at birth), who supports and/or advocates for transgender and non-binary people. It can seem daunting to be an ally with all the hate in the world – sometimes, I think I would rather hide until everything feels just a little safer – but for those I love, I can’t. Besides, there are simple actions we can take to be a better ally, right now.

It starts with education

There are 100,815 transgender and non-binary persons in Canada, according to Statistics Canada. That’s 1 in 300 Canadians. Gender refers to an individual’s personal and social identity. Transgender refers to people whose gender does not correspond to their sex assigned at birth (based on a person’s reproductive system and other physical characteristics). Non-binary refers to people who are not exclusively a man or a woman. In both cases, the gender identity, which is the experience of gender internally, does not match what society expects.

Maybe, as an ally, you are familiar with these terms, but do you know about the history of trans and non-binary rights in this country? Have you read any trans or non-binary-authored resources lately? Being a good ally is more than being a friend; it is important for us to educate ourselves about the lived experiences of trans and non-binary people to better understand what they encounter daily. And we have to educate ourselves. It is critical to consider where we put the burden of this work.

Names and pronouns

For many transgender and non-binary people, names and pronouns are an important issue. They may find themselves constantly on the receiving end of being called by their old (“dead”) name or the wrong gender or pronoun (“misgendered”), which can be incredibly hurtful. The most respectful approach is to introduce oneself using one’s preferred name and pronouns and ask if you’re not sure. Mess up? Respectfully apologize, then concentrate on correcting yourself moving forward.

Safety

Allyship is incredibly important in keeping transgender and non-binary people safe – especially in today’s politically charged climate. And it can start young. Mae Ajayi, who is non-binary and a parent, says making allies of our kids is one of the best ways to keep trans and non-binary kids safe.

“It’s about having conversations with kids that are really explicit about transphobia,” Ajayi says. Explaining what it is and how to be an ally is a helpful start, says Rachel Malone, parent of bigender Sacha, and cisgender Peter. “We can’t wrap our kids up in bubble wrap, right? And we can’t be there 100 percent of the time, so we can’t be their only protectors.” Malone knows there is a lot to do to improve safety for transgender and nonbinary people. She told me how Sacha’s brutal bullying over her gender identity in kindergarten resulted in serious mental health concerns and asked me not to use her or her children’s real names because of reports of families of transgender kids being targeted with violence.

Safety is a theme not only for children but also for transgender and non-binary adults, who are more likely than cisgender adults to experience violence. Allies who stand up for their transgender and non-binary friends, colleagues and neighbours are crucial to improving safety for these adults.

Mental health

Robyn Letson, MSW, RSW, is a trans social worker and psychotherapist who works with transgender and non-binary clients. According to them, “There is huge potential for allyship in providing affirming mental health care to trans and non-binary people.”

Transgender and non-binary individuals are more likely than cis-gender individuals to live with poor mental health. This could be due to a variety of reasons, but the transphobia, prejudice, and discrimination that they experience just for existing certainly does not help.

An ally can help support the mental of transgender and non-binary people by being supportive, respecting their privacy by not asking invasive medical questions about transition or hormones, and seeking their feedback on how you can adjust your care approach (you may not know that your approach isn’t working unless you ask). You can signal with signage that workplaces, schools, and clinics are safe and affirming spaces for transgender and nonbinary people.

It also takes work to really help support the transgender and non-binary folks in your life. “I would suggest starting with critical self-reflection,” says Letson. “For cis people who want to begin or deepen a journey of practicing better allyship and solidarity with trans people, I always suggest beginning with one’s own relationship to gender.”

Ongoing commitment

There is no “completed” badge for being an ally – it is all about continuous education, working against discrimination and transphobia, and challenging one’s own biases.

“Make space for fewer assumptions and just allow yourself to feel like you don’t know,” suggests Mae Ajayi. “Cis(gendered) folks should understand how sad and scared people are right now and that it feels very frightening as a trans person and also as a parent – it’s a very real danger,” they say.

I can only imagine how frightening it is to be a transgendered or non-binary person in Canada right now, and as an ally, that makes my blood boil. However, being angry isn’t enough – being cisgender is currently a privilege in our society, and it is an ally’s responsibility to use that privilege to act.

It sounds like a big job, but if you start with supporting transgender and non-binary people, work on educating yourself, commit to learning and using the correct names and pronouns, think about protecting their safety, support their mental health, and then make an ongoing commitment to act against transphobia and discrimination, you will be well on your way to being a better ally.

Jessica Ward-King

BSc, PhD, aka the StigmaCrusher, is a mental health advocate and keynote speaker with a rare blend of academic expertise and lived experience. Equipped with a doctorate in experimental psychology and firsthand knowledge of bipolar disorder, she’s both heavily educated and, as she likes to say, heavily medicated. Crazy smart, she’s been crushing mental health stigma since 2010.