Related Articles

I’m going to go to a bit of a dark place, and I would invite you to follow me there because it is important. I have had (and the way bipolar disorder goes so cyclically, likely will have again) suicidal ideation, and I would like to tell you what it is like. I’ve never told anyone this before, but I would like to tell you this now because of suicide awareness day, which is commemorated each September 10 in honour of all those who have died by suicide and those living with suicide attempts or suicidal ideation and their loved ones.

Suicidal ideation, or thoughts of suicide, are undoubtedly different for everyone, so I can only tell you about my experience. If my experience can make even one person feel seen or understood, it will be worth it.

Most often, my thoughts of suicide are passive, as in “I would be better off dead” or “It would be better if I didn’t wake up.” These are the thoughts I will be describing in this blog post. Certainly, when I am in more distress, these thoughts can become more active, culminating, for me, in plans to die by suicide, but these are more rare (and these, particularly when accompanied by plans, are where interventions need to be made by loved ones and mental health professionals).

For me, my thoughts of suicide are a study in opposites. They are equal parts horrifying, foreign thoughts, and soothing, familiar thoughts. Let me explain what I mean. Thoughts that I would be better off dead come unbidden into my mind and are not welcome there. I am deeply ashamed of them. I know they are “deviant” (at least, I choose to label them as such), and they seem to come at me from some outside force, and I don’t want them to. But at the same time, they are soothing and familiar – they offer a way out of a situation that I have thought through and thought through and for the life of me cannot find a way out of (my depression). They offer a seductively easy way out of my situation at that, almost like a mother soothing me with a “there, there” and a pat on the back, promising me that it will all be alright – there is a solution (and it is easy).

Suicidal ideation changes volume, too. Sometimes, it is a whisper in the back of my mind, barely there but just audible. Sometimes, it is insistent, like a child asking for screen time tugging at my sleeve. Sometimes, it feels like it is literally screaming to be heard, and nothing else can drown it out and I am just left to listen to it suggest, cajole, demand, insist and request that its ideas be heeded.

Does having these thoughts mean that I am planning to die by suicide? No. As dark and insistent as they are, these thoughts are just thoughts. Just like the thoughts in traffic that you would like to ram that car in front of you or any of the other fantasies that pass through your mind throughout your day, suicidal ideations are just that – fantasies. Fantasies that make life more livable. It is because they are so stigmatized that they are so frightening and so difficult to talk about. Now, we have to be careful to walk the line between reducing the stigma around suicide and making it a genuine option, but I believe that that line is thick enough that there is room to reduce the stigma and give relief to people like me, who struggle with guilt and shame over their suicidal thoughts to the point that they won’t seek help.

So, with that, what makes up the resistance, you might ask? What’s the good news story here? I am lucky. I have a partner I can talk to about these scary thoughts. She doesn’t buckle and collapse. She listens calmly, stroking my hand all the while. Then she asks if I have any plans. She asks what we should do – should we call my psychiatrist (whom I am also fortunate to be able to disclose suicidal ideation to without being summarily put in the hospital) or take me to the hospital, or are we safe just to wait and see, and then she lays with me while I cry. I am lucky. Not everyone has a partner or loved one like this because not everyone understands that just having these thoughts does not mean that I am imminently in danger or, worse, “crazy.” Most people, when they hear of suicidal thoughts, get quite scared themselves, and they lose themselves in that fear. Please, don’t. I assure you, your loved one who is telling you this is more afraid than you are. Keep your cool. Better yet, before you are ever in this situation, get some basic training that will help you cope, like Mental Health First Aid (MHFA) or even more specialized suicide assistance training. Courses like this will help you to be able to assess risk and figure out what to do next, whether that is simply being with your loved one or whether that is making a safety plan and getting help.

Suicide is not something that affects other people. In this country, 12 people die by suicide every day – and that is just the deaths that are verified as suicide. Due to stigma, many deaths are attributed to other causes rather than bringing shame to a family or community. It is the second leading cause of death among youth and young adults (15-34 years), and 12% of Canadians admit to having had thoughts of suicide in their lifetimes. We all love someone who is thinking about or will think about dying by suicide. I hope this little piece of vulnerability will help at least one of them.

BSc, PhD, aka the StigmaCrusher, is a mental health advocate and keynote speaker with a rare blend of academic expertise and lived experience. Equipped with a doctorate in experimental psychology and firsthand knowledge of bipolar disorder, she’s both heavily educated and, as she likes to say, heavily medicated. Crazy smart, she’s been crushing mental health stigma since 2010.

Subscribe to Catalyst

Subscribe to get our magazine delivered right to your inbox

Related Articles

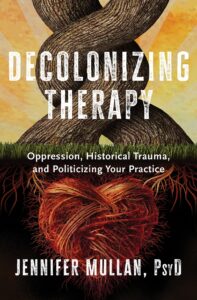

Author Dr. Jennifer Mullan’s new book takes a critical look at care.

There are too many roadblocks to care, resulting in “an outdated system of wellness that is void of wellness.” So says Dr. Jennifer Mullan, a New Jersey-based clinical psychologist and author of the forthcoming book, Decolonizing Therapy: Oppression, Historical Trauma, and Politicizing Your Practice.

According to Mullan, many of those seeking care run into obstacle after obstacle, an experience that reflects what she calls the mental health industrial complex. In response, she has become part of a “growing movement of practitioners who are unlearning colonial methods of psychology,” which seeks nothing less than completely overhauling and restructuring the system.

The book’s 10 chapters are full of scathing observations and critical insight, with titles like “From Lobotomies to Liberations,” “Diagnostic Enslavement,” and “Emotional-Decolonial Work.” Throughout its 400-plus pages, Mullan explores a wide range of problems impairing the mental health system in the United States and elsewhere.

These systems operate like revolving doors, processing many clients but hardly ever dealing with an individual’s pain at the root level. She is convinced that this shortcoming helps explain the spasms of violence erupting with increasing frequency across the U.S., such as school shootings, rising depression levels, and increases in mental health concerns.

Mullan has spent much of her career conducting therapy sessions with children and adults who have experienced domestic violence, unhealthy substance use, child abuse, poverty, and gender identity issues. Over the years, these encounters have chipped away at her optimism and fuelled her frustration.

Ignoring the past

While Mullan’s book examines many different roadblocks to effective treatment, her most blistering criticisms are reserved for the system’s failure to acknowledge intergenerational trauma — which she insists is the root cause of many mental health problems.

She therefore sees her book as “a CALL to ACTION to mental health practitioners, space holders, and wellness workers everywhere. If we are to ‘treat,’ heal, and educate the individual, the group, and/or the organization,” she asks, “is it not essential to also include history, life experiences, and cultural traumas?”

Intergenerational trauma is not a new concept. It gained credence when researchers started studying the impact of the Holocaust perpetrated by Nazi Germany. Nowadays, a growing body of Canadian-led research links the abuse suffered at residential schools with this same kind of trauma. A Historica Canada video describes the experience this way: “For many, the trauma of the mental, physical, and sexual abuse [residential school survivors] suffered hasn’t faded. The children and grandchildren of survivors have inherited those wounds; they have persisted, manifesting as depression, anxiety, family violence, suicidal thoughts, and substance use.” A definition from the American Psychological Association describes how such trauma can make its way across generations. It is “a phenomenon in which the descendants of a person who has experienced a terrifying event show adverse emotional and behavioral reactions to the event that are similar to those of the person himself or herself. These reactions vary by generation.”

Mullan draws heavily on these themes in Decolonizing Therapy, pointing to the history of slavery, internment camps, dictatorships, and residential schools, while arguing that the failure to look at these events dooms future generations to ongoing cycles of pain. Her prescription for therapy means not only exploring family history but probing culture, traditions, rituals, religious beliefs, and practices. Once the buried trauma is revealed, the patient can then receive more focused treatment.

Unfortunately, most therapists are taught almost nothing about revealing intergenerational trauma and are often cautioned against bringing up the past.

“The way many therapists and social workers have been educated,” she says, “is to consistently keep a blank slate, don’t have opinions, don’t have anything in your office that is too forward-facing or political. We’re not going to talk about Black history. We are not going to talk about enslavement. We are not going to talk about racism.”

Waiting and wanting

What is discussed in counselling sessions usually amounts to a short conversation with little time to delve deeper into an issue. Mullan underscores the point by recounting a colleague’s workload at a community clinic that involved more than 90 clients over two weeks. In Mullan’s previous work as a university staff psychologist, she said that nearly 100 students were on a counselling wait-list for six months straight. “Resources have been poorly and criminally allocated,” she says. So, in many settings “money needs to be reallocated.”

A related issue is the crushing workload, which is causing mental and physical health problems for therapists themselves. The book details dismal conditions some therapists are experiencing, such as working other jobs to meet basic needs, paying student loans, dealing with intense vicarious trauma due to the material they are helping to hold, being overworked with up to 80 or more cases a month, moving from job to job, experiencing burnout, and receiving constant microaggressions, bias, and acts of discrimination.

One therapist quoted in the book describes the aftermath of a heart attack she’d had in her office. “It’s not their fault. I thought it was my fault. I changed my diet and worked out more. I went back to work and had panic attacks in between clients. My supervisor told me, ‘You need to get more rest. Are you sleeping? Seeing a therapist of your own?’ No self-care is gonna fix my heart and my anxiety and my nervous system.”

Changing gears

A few years ago, Mullan decided to stop accepting patients and concentrate on reforming the system through public speaking and writing her book, which also lists ideas for deeper reform.

While her views were shaped in the U.S., her calls for change will likely get a thumbs up in many countries. Here in Canada, initiatives like Stepped Care 2.0 are already in place in Newfoundland and Labrador, the Northwest Territories, Nova Scotia, and elsewhere that have radically reduced wait times for mental health services. More organizations are also recognizing Indigenous ways of healing to provide informed and culturally aware forms of therapy. As well, a recent program by the Mental Health Commission of Canada and the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health culturally adapted cognitive behavioural therapy for South Asian communities.

Like many publications covering mental health, Decolonizing Therapy includes exercises, review questions, and detailed references. What makes it stand out is its feisty, passionate, and challenging voice — and Mullan’s personality, which is always present. “I’m holding the Mental Health Industrial Complex accountable and, along with you dear reader, I’m demanding change,” she writes.

Her views are perceived as controversial in certain circles, and some in the profession do not support her activism: a former professor she respects advised her against mixing psychology and politics. Yet Mullan sees it otherwise. In fact, by putting tough topics front and centre, the book is intentionally designed to change that narrative.

Resource: Fact Sheet: Common Mental Health Myths and Misconceptions

Further reading: CBT For You and For Me: A suite of culturally adapted cognitive behavioural therapy tools is designed to break through barriers.

Subscribe to Catalyst

Subscribe to get our magazine delivered right to your inbox

Related Articles

When one size does not fit all. A look at Waypoint’s approach to structured psychotherapy.

There’s a specialty mental health hospital on the shores of Georgian Bay in Penetanguishene doing especially innovative work these days. In addition to its 301 beds, the Waypoint Centre for Mental Health Care is home to Ontario’s only high-secure forensic mental health program for patients served by the mental health and justice systems. The range of services covers acute as well as longer-term psychiatric inpatient and outpatient services for the region. Of late, their delivery of the Ontario Structured Psychotherapy (OSP) Program is receiving recognition for its ability to have a major impact.

I was honoured to present the group, which includes Jessica Ariss, Waypoint’s program manager, and Jeannie Borg, director, of system innovation at the Waypoint Centre, with the 2023 Award of Excellence in Mental Health and Addictions Quality Improvement from the Canadian College of Health Leaders in June. I asked the team about their approach to improving mental health outcomes.

Transformative care

The OSP offers publicly funded treatment for individuals experiencing depression, anxiety, and anxiety-related conditions by providing access to short-term, evidence-based cognitive behavioural therapy (or CBT), a form of care that helps people examine how they make sense of what’s happening around them and how these perceptions affect the way they feel.

Waypoint delivers CBT via partnerships with more than 20 organizations, meaning that people can access care in their communities rather than having to travel to a central hub. Through this model, the therapy is offered at no cost to clients. While it’s a highly effective treatment that improves symptoms and reduces the likelihood of mental health concerns becoming critical, Waypoint is far from the only organization offering CBT.

So what makes its program different and award winning?

Mind the gap

Waypoint won the award for its tenacity in addressing gaps in care. They did so by working to enhance access to CBT for priority populations, including Indigenous, francophone, and 2SLGBTQI+ individuals, which increased referrals to its programs. In one instance, Waypoint used its communications channels to promote the services to priority communities online and track the path from clicks to referrals. This part of the project took a wrap-around approach that covered training, communication strategies, and service modifications. Those modifications were informed by advisory circles that included patients and others with lived and living experience from various communities.

Members of the OSP Program and the Indigenous Health Circle, who worked together to adapt and enhance services for Indigenous clients: (from left) Charity Fleming, David Thériault, Jessica Ariss, Germaine Elliott, Leah Lalonde, Melissa Petlichkov, and Melissa Moreau.

For Indigenous populations, the Waypoint team worked with the Indigenous Health Circle, B’Saanibamaadsiwin, and the Barrie Area Native Advisory Circle to develop clinical protocols and integrated care pathways for CBT services. These were based on client feedback, research evidence, and a training course (offered by Wilfrid Laurier University) called Sacred Circle CBT — Mikwendaagwad, an Anishinaabemowin/Ojibwe word for “It is remembered, it comes to mind.” The Indigenous service pathway — called Minookmii or “sacred tracks upon the earth” — uses an adapted intake assessment process conducted by an Indigenous clinician and services that include spiritual healers. These Indigenous health promotion practices ensure that the perspectives and needs of priority populations are central to Waypoint’s service development and evaluation processes.

Data and demeanour

The organization tracks those processes using a dashboard system that takes quantitative and qualitative measures into account. Qualitative feedback is incorporated into clinical reviews as part of a continuous improvement loop. But Waypoint never lets its commitment to dashboards and data inhibit the personal touch. It has mastered the balance between analytics and empathy, making sure that the human elements and the patterns add up to meaningful care.

For example, a clinician will meet with a client to determine the service that best fits their needs. Whether it’s a sweat, a smudge, connecting with an Elder, or another Indigenous approach to care — or something else like clinician-assisted bibliotherapy — it’s about meaningful, involved, and engaged care. As one participant put it: “Within the first few minutes of our meeting, the therapist I was paired with created a space that felt safe for sharing. Her kindness, knowledge, and warm demeanour encouraged me to speak more honestly and openly about my anxiety than I ever had before. She shared information, statistics, studies, anecdotal evidence, and examples that helped me to see my health anxiety from a different perspective — and also to make me feel less alone in my struggles.”

It’s these differences that make the program stand out, something that Heather Bullock, Waypoint’s vice-president of partnerships and chief strategy officer, sees as notable.

“The program runs close to its vision,” she points out. In other words, these elements are not nice-to-haves; rather, they are embedded processes. “There’s no gap between the vision and reality,” she says, citing their work with colleges, clinics, and different cultural environments. “We’ve managed to come together as communities and as different types of providers under a shared goal. We’re building something the way we want it to be built — and that’s something that aligns not with what we need in the future but with what we need today.”

Resource: Webinar – E-Mental Health and Indigenous Partnerships in Suicide Prevention. How Kids Help Phone uses e-mental health services to break down access barriers to inform its suicide prevention work.

Further reading: The Catalyst: Conversations on Mental Health article. CBT For You and For Me.

Related Articles

Do you feel like you always have to be doing something? Do you find it difficult to let go of your to-do list and just relax?

I needed to go through burnout to learn that there are drawbacks to being a ‘high achiever.’ The pursuit of excellence comes at a cost. Relentless busyness is not good for us.

Doing, doing, done

Do you ever notice the pressure to ‘be your best self,’ whether in your job or as part of your persona on social media? If you are reading this, I am guessing that you are pretty much tied to your phone and your media feeds. The irony is that we often turn to our devices to relax, but this actually speeds us up and can make us feel even more frazzled.

Constantly checking off the items on your to-do list may lead you to feel like you’re accomplishing things and being productive, but it can spiral into an unbalanced and unhealthy way of living. And if the point is to ‘live your best life,’ it can actually be counterproductive.

“The high value put upon every minute of time, the idea of hurry-hurry as the most important objective of living, is unquestionably the most dangerous enemy of joy. My advice to the person suffering from lack of time and from apathy is this: Seek out each day as many as possible of the small joys.”

Hermann Hesse

Higher, stronger, faster

Do more. Be more. Get more. The pressure to perform can impact your mental health. I wrote about this in a previous post. The problem with the achiever mindset (achievement more than anything else), which is reinforced by the cult of busyness, is the mistaken belief that by focusing on the external markers of success, we will lead a good life. It’s a false promise that the sacrifices we make now will pay off with happiness in the future. So, we deprioritize what brings us spontaneous joy, and important relationships, with the assumption that we can enjoy those things after we achieve our goals.

“Our enjoyment of life is taken from us by the not-enoughness at the hollow heart of consumerism.”

Wendell Berry

The difference between productive and busy

Productivity is different from busyness. And being busier does not mean we are more productive.

Actually, when you are at your busiest, that’s when you need to slow down. Slowing down and taking breaks lets your brain rest, resulting in better focus, efficiency and results.

Productivity has more to do with having time to do the things that matter. When things are in balance, we can handle our day-to-day commitments, and we feel like we have the time to rest, be present, and enjoy life.

Get unstuck

How do you slow down and get off the hamster wheel? How do you become more present, creative, and connected to those around you?

Happiness shouldn’t be put off until the weekend. You can feel it right now, at this moment. Focus on the moment and find ways to appreciate where you are right now.

Try these tips for slowing down

- Set up some reminders for yourself to slow down– post-it notes, reminders on your phone, or whatever works for you

- Try spending some time doing nothing, or as little as possible

- Decrease your screentime

- Go outside, or try forest bathing

- Try meditation or mindfulness

- Do more physical activity, preferably in nature

- Journaling

- Stop waiting for everything to be perfect

To recap, here’s why we need to slow down:

- The way we live now, there is a lot of pressure to be busy, to multitask, and to be as productive as possible

- When we multitask, our minds are racing, reducing our effectiveness

- Slowing down can help us become more present, joyful, and connected to those around us

Author: Nicole Chevrier

An avid writer and photographer. A first-time author, she recently published her first children’s book to help children who are experiencing bullying. When she isn’t at her desk, Nicole loves to spend her time doing yoga and meditation, ballroom dancing, hiking, and celebrating nature with photography. She is a collector of sunset moments.

Related Articles

I was driving my car down the street, heading to a movie with a friend, when all of a sudden: WHAM! A pothole. My tire was in there before I could react, and I don’t know what it did – bent my alignment or twisted my suspension or something (can you tell I’m no mechanic?) – but the next thing I know, I am stranded by the side of the road and being towed to the shop, facing a very hefty bill and a long process just to make her roadworthy again. And I missed my movie.

I feel like my life with a mental illness is like that sometimes. I can be cruising along just fine when some bump in my path derails my whole journey leaving me miffed, frazzled, phoning for help and not really knowing what is going on, missing the things in life that I enjoy, and facing a long (and often expensive) road to recovery.

Now, if you’ll indulge me in sticking with the car metaphor for a while, no amount of oil changes, brake jobs, or filter changes were going to prevent me from hitting that pothole or from my car getting damaged. And that, I propose, is the difference between mental health and mental illness.

Mental health is the general running of my car. I can take care of it – get regular services, change the wipers, fill the reservoirs, change the filters, and keep it clean – or not, and so, the general condition and running of my car can be good or not. Mental health is just like that. We can do the things we need to do to keep ourselves in tip-top condition or neglect our self-care and just barely keep running on fumes.

Mental illness is what happens when something actually goes wrong with my car – it breaks down or gets damaged. Poor maintenance can contribute to things going wrong, to be sure, in both cars and mental health. But sometimes, those (literal or figurative) “bumps in the road” break an axle and send you calling for help and needing care before recovery can happen. They can come out of the blue (like my pothole) or out of a longer, more drawn-out process of becoming worn down (say, wearing out your brakes), but either way, a trip to the professionals for some help is the result.

I mentioned the expense of getting my car fixed by a professional mechanic. Sometimes I can call my dad, or a friend, to come and help me – tweak something, fill a reservoir, change a fuse, that sort of thing. But sometimes, the only way I am going to get my car to run again is to take it to the mechanic. That is sort of frightening and not always accessible – sometimes, I can’t afford either the time or the money it will take. Getting help for my mental illness is like that too. It takes time, and, in the case of private psychotherapy and prescription medication, it can have significant costs. And not everyone can afford it.

No metaphor is perfect, and this one, too, cannot be taken too far or too literally, but it can be helpful to think through the differences between mental health and mental illness and how they are connected.

I missed my movie, but my friend picked me up from the shop, and we got takeout and streamed TV instead. Then I dusted off my bike and made it to work the next day – with sore legs, but successfully. Having my car break down wasn’t the end of the world, and with some time, money, and effort (which I am privileged to be able to invest), I got my car back on the road. My life with mental illness is like that, too – with the help of friends and family, I keep living life (not without hiccups and disappointments but living it nonetheless!) and eventually end up back on my road to recovery.

Author: Jessica Ward-King

BSc, PhD, aka the StigmaCrusher, is a mental health advocate and keynote speaker with a rare blend of academic expertise and lived experience. Equipped with a doctorate in experimental psychology and firsthand knowledge of bipolar disorder, she’s both heavily educated and, as she likes to say, heavily medicated. Crazy smart, she’s been crushing mental health stigma since 2010.

Subscribe to Catalyst

Subscribe to get our magazine delivered right to your inbox

Related Articles

Getting started on a new plan for meaningful change

“I used to believe I was a bad person trying to be good,” says Steven Deveau, executive director of the 7th Step Society of Nova Scotia, a peer-run organization offering support to individuals who’ve been incarcerated. “My mindset changed when I realized I was a sick person trying to get well.”

As a person with lived experience of criminal justice involvement, Deveau’s sentiments could be widely shared among those who interact with the criminal justice system. Among federally incarcerated individuals, 73 per cent of men and 79 per cent of women meet the criteria for one or more current mental health disorders. Such statistics point to a need for increased access to quality mental health services, both within corrections and the community, as well as other prevention and early intervention supports like housing and education. As with all mental health concerns, it’s critical to ensure that people get help when they need it. Yet tangible progress toward these goals has so far been wanting.

Not just another report

“People ask me for my opinion. They ask, ‘What can we do to make things better?’” says Mo Korchinski, executive director of Unlocking the Gates Services Society. “And then it sits on a desk, and it stays in a report. I just want to see action.”

Inspired by this and other calls to produce meaningful change, the Mental Health Commission of Canada (MHCC) is developing an action plan for Canada to support the mental health and well-being of people who interact with the justice system. It draws on the expertise of those with lived and living experience, along with other experts who have highlighted these issues for years. The action plan also relies on relevant work from the past two decades — including the MHCC’s 2012 Mental Health Strategy for Canada, which lists criminal justice as a priority — and what is currently being done to focus on actions capable of implementation. The scope of this national project will be broad and comprehensive, including a focus on upstream prevention and early intervention, structure, law reform, and system transformation, and an assessment of mental health supports for all types of criminal justice involvement, from first contact with police to community reintegration and every stage in between.

Inside the system

“I articled in a criminal court duty counsel office, and in that role I immediately recognized the intersectionality of mental health and the justice system,” says A.J. Grant-Nicholson, principal lawyer with Grant-Nicholson Law and project adviser for the action plan.

A.J. Grant-Nicholson

“All too often, I saw accused persons with cognitive challenges, trauma, psychiatric illness, and/or substance use and mental health concerns that related to their criminal charges. Quickly, I deduced that the justice system was the system of last resort — and sometimes the default system — for persons with mental health-related issues,” he says.

Grant-Nicholson’s career has long been focused on the topic. Following his articling program, he worked as a mental health staff lawyer at Legal Aid Ontario, the first position of its kind in the province. There, he represented clients who came before the Consent and Capacity Board and acted as duty counsel at a forensic psychiatric hospital as well as in mental health court.

“I observed that the justice system was not an ideal place to remedy mental health conditions,” he says. “Defence lawyers, prosecutors, justices of the peace, and judges are not clinicians. Criminal law is a blunt instrument that is limited in its ability to provide therapeutic support for accused persons with mental health-related needs.”

Grant-Nicholson acknowledges that there is “increasingly more mental health support in criminal courts, such as having a designated mental health court where accused persons can be connected to mental health workers and mental health-related programming.” However, he finds that “the availability and overall level of support is not consistent across all jurisdictions — and sometimes, accused persons are not aware of the mental health supports available to them.”

As a legal representative for detainees, Grant-Nicholson has seen a significant portion of incarcerated people with serious mental health and/or addiction issues, and he finds the intersection between mental health and the justice system readily apparent in detention facilities.

“It has been my experience that correctional institutions are suboptimal for mental health recovery and that incarceration itself exacerbates mental illness,” he says. “I have also seen the frequent pattern of clients with mental health conditions backsliding once they are released from detention and, subsequently, their almost inevitable re-entry into the justice system. This is often due to barriers in accessing health and social services in the community and/or finding suitable housing when they are discharged or released.”

Seeing these gaps, Grant-Nicholson is seeking to make meaningful change. “My hope is that the action plan will provide stakeholders with insights so the justice system will be better equipped to support mental health, and over time, fewer people with mental health conditions will be incarcerated and the recidivism rate will decrease for this population.”

Grant-Nicholson says that is why an action plan for Canada on mental health and criminal justice is so vital. Deveau of the 7th Step Society of Nova Scotia also sees hope with the project and the people who are part of the committee. It has the power to change lives and change communities, he says.

“I have this saying that I woke up today sober and not in prison — the physical or the mental one — so it’s a good day,” he says. “Some of the smallest things can be the greatest motivators.”

Learn more about the action plan and how you can contribute to its success.

Resources: Mental Health and Criminal Justice: What is the Issue?

Further reading: A Name and a Face: A filmmaker illustrates how easy it is for someone living with mental illness to end up on the street or get caught up in the criminal justice system.

Subscribe to Catalyst

Subscribe to get our magazine delivered right to your inbox

Related Articles

It’s time to reframe masculinity — one step at a time

Beyoncé and Kendrick were crooning about America’s problems as our truck wound its way toward the trail. My husband, in the driver’s seat, was his usual jovial self as he chatted about music aligning with historical movements. It was 6:30 a.m. My husband is disgustingly and unabashedly a morning person, and we were on our way to an eight km hike along the Gatineau escarpment in Quebec.

Our son — who is in no way a morning person, or a hiker — was in the back seat. He was in charge of the music, and he was there to win a bet.

Despite my more taciturn demeanour, I was happy to be heading out that morning for the anticipated hike. It was the dynamic brewing between father and son that had me feeling cautious. Men can be weird and competitive, even when they’re trying to be chill.

Macho, Macho Man

The machismo started in the parking lot when my son stepped out of the truck wearing a sweater and holding his coffee.

“Leave your sweater and coffee here,” my husband said, which prompted my son to slip on his mutinous face and grip both his coffee cup and his sweater with determination.

Before the world’s dumbest argument over knitwear and a travel mug could unfurl, I said to my husband, “You’re not carrying it or wearing it, so stop trying to control it.” To my son, I added, “It’s going to be hot, and there will be bugs — are you sure you want to bring those?”

I started the hike in the lead spot to avoid the inevitable male jockeying for the alpha position. This is one of the reasons I think men are weird. Why does it matter who goes first? It’s not a race. There are no prizes. Societal norms do men no favours when they inspire them to be dominant.

My son has no idea which direction we are taking, and yet he edges forward to take the lead. My husband, who regularly encourages me to go first when it’s just the two of us, suddenly wants to set the pace. The scene makes me think it’s no small wonder that men’s mental health is in the state it is. How can you seek help when you are convinced you should have all the answers?

Yes, I know, not all men are the same. But the statistics weigh heavily and are unignorable.

In Canada, 12 people die by suicide every day — with Statistics Canada reporting up to 4,500 annually — and men’s suicide rates are three times as high as women’s.

According to research by the Mental Health Commission of Canada, compared to men in the general population, Indigenous men exhibit higher rates of suicidal behaviour, including suicidal ideation, attempt(s), and death. Suicide attempts are 10 times as high among male Inuit youth, compared to non-Indigenous male youth, and compared to heterosexual men, sexual minority men (such as those who identify as gay, bisexual, or queer) are up to six times as likely to experience suicidal ideation.

Boys don’t cry

My husband is brilliant in many ways — including being low-key when big things are happening to him — but I’m starting to wonder if this stoicism by him and our male friends is a mask for bottling emotions, something men are socialized to do. Health issues? It’ll go away on its own. Business problems? No big deal. Family woes? Don’t go there.

When you give it any thought at all, the statistics should come as no surprise. Men living in environments where they are expected to uphold norms such as strength, toughness, and self-reliance can feed into negative beliefs about mental health. Men who adhere strongly to these norms may find it more difficult to recognize signs of mental illness in themselves and others and be less likely to access mental health support.

Reframing “masculinity” to allow greater expression and recognition of emotion and help seeking is a good first step.

A new generation is getting this lesson at Eskasoni First Nation on Cape Breton Island. GuysWork, a Nova Scotia program that started in 2012, bills itself as “a safe space to address masculine toxicity.” It does so by having male facilitators talk with groups of adolescent boys about different issues — things like health care, mental health resources, intimate partner violence, and keys to healthy relationships. Elsewhere, NextGenMen’s Cards of Masculinity box set presents 50 bold questions on topics like objectification and hook-up culture to facilitate meaningful discussions about boys’ beliefs and behaviours.

These organizations are working to change the narrative of outdated masculinity that leaves men feeling isolated, unable to express their emotions, and reluctant to seek help when they need it.

Such collective efforts help de-stigmatize mental illness among men, enhance the quality of health-care provider relationships, and open new pathways for building better personal relationships.

Programs that allow for “shoulder-to-shoulder” action-oriented tasks (think camping, sports, art, auto mechanics), rather than face-to-face talk-focused therapy may help get the conversation going.

Moving forward

Back on the trail, my husband points to the preferred path up a rocky incline. My son, of course, takes an alternate and more complex route. Nope, no obvious symbolism there.

We dragged him out of bed to hit the trail because we were getting worried — he needs to do more to get his physical and mental well-being in order. So, my husband bet him he couldn’t get up early enough to join us.

My husband used to run to keep in shape, but after a series of health issues took running off the table, I started to worry about him. I suspect he did so as well. Then we discovered that, while he could no longer run, he could hike — and the world shifted. Running in the neighbourhood was good, but hiking in the forest was transformational.

Even better, hiking is something my husband and I could do together. Some of our best and most rewarding conversations have happened on the trail. We’ve tackled work problems while admiring wild trilliums and resolved deeply personal issues while glimpsing white-tailed deer. Talking things through is good for us; it makes us reflect more.

As we approach the trail’s end two hours later, my son is in the lead. His sweater is around his waist, his coffee mug is full, and we’re all smiling.

Resource: Men’s Mental Health and Suicide in Canada — Key Takeaways

Further reading: Weaving Through the Challenges: The ABCs of Finding Paths to ACB Mental Health Care

Subscribe to Catalyst

Subscribe to get our magazine delivered right to your inbox

Related Articles

If it’s just not working, then don’t ghost. Name your needs.

In a famous episode of the popular TV series Curb Your Enthusiasm, Larry David, the curmudgeonly main “character” (said to be an exaggerated version of himself), decides he must end therapy after seeing his middle-aged psychiatrist at the beach in a thong. When he announces his intention to leave, the psychiatrist seems surprised by the decision and keeps pressing Larry to tell him why it’s over. Larry keeps hedging, then ungracefully bolts.

In reality, the question of why and how to end therapy — to “break up” with your therapist — is for most more complicated than this scenario suggests. Ideally, the decision to move on is mutual, anticipated, and planned. If your therapist is a good fit, and you’ve developed a trusting relationship, you’ll both probably know when it makes sense to do so. It’s also likely that you’ll be able to discuss it openly: you’re feeling better; you’ve worked together toward gaining insights on the challenges that brought you into therapy, you’ve grappled with grieving, worked to improve or let go of toxic relationships, begun to heal from trauma, etc. Now, you both sense that you have the tools and understanding to deal with situations that trigger anxiety or other issues. You’ve grown, your therapist has genuinely helped you, and with respect and goodwill on both sides, the time to part has come.

But what if you and your therapist are not such a good fit? They’re just not “getting” you, and it seems unlikely that you’ll feel better any time soon. While the most frequent advice is to “shop around,” in practice it can be hard to tell your story — in all its intimate, painful details — multiple times to different strangers. That kind of reluctance can tempt you to stick with the therapist you’ve been working with, despite your reservations.

At this point, it’s all too easy to rationalize your way back into familiar territory. Maybe you’re relying on community or employee services, where choices are more affordable. Maybe you have trouble asserting yourself. Maybe you don’t want to say something that might hurt your therapist’s feelings or invite some kind of judgment. While each of these reasons might be valid, continuing on when you’re not fully invested will be an unfortunate waste of time for you both.

Take “Jean,” for instance, a woman in her 60s who sought therapy when she found herself stuck getting over the death of a pet. Her online therapist, a woman in her 30s, seemed to pigeonhole Jean as a lonely empty nester who needed to get out more. “Yet I’m not lonely,” says Jean, a creative spirit who is happily married, sees her grown children often, and enjoys a wide circle of friends. “She was very nice, but she was off about who I am.” Jean felt stereotyped, but being conflict-avoidant, didn’t know how to convey it. She ended up leaving after completing several sessions and didn’t seek out another therapist. Eventually, she moved past her grief on her own, without the external help and insight she had been looking for. Jean still wonders if, with the right therapist, the process might not have taken so long or been so painful.

So, though it may not be easy, if you’re dissatisfied for any reason, you owe it to yourself and your therapist to communicate your feelings and end the therapeutic relationship.

Starting well

Of course, incompatibility can be avoided by finding a good fit from the beginning. Many therapists detail their specialties and training in online biographies, which makes it easier to narrow the field and choose someone with expertise in what you’re experiencing — someone who has a good chance of understanding and appreciating who you are and what you need.

According to Lindsey Thomson, a registered psychotherapist based in Kanata, Ontario, and public affairs director for the Canadian Counselling and Psychotherapy Association, with 13,000 members across the country, as you go through this process “it’s important to be truthful about your preferences. Let’s say you’re a woman who wants to work on your experience of a past trauma that makes you uncomfortable talking with a man. Or maybe you’re part of a marginalized community and feel more comfortable with someone who shares the same cultural background. If you have preferences like that,” she says, “you need to find someone who meets them.” Many therapists, including Thomson, offer a 30-minute complimentary session to help potential clients test the waters and see if the fit is good for both people.

Also essential is understanding what type of therapy the counsellor is offering and what their overall philosophy is. As Thomson points out, studies suggest that what matters most is the dynamic between client and therapist. “This is a working relationship we’re dealing with,” she says, “you know, human to human. If something comes up that you don’t agree with, or if you don’t like the way the therapist has framed something — or you were challenged, and you weren’t ready for it — bring that up. It’s really important. Yes, it can be uncomfortable. But just know that all therapists want to know what’s going on for you in that process.”

Definitely don’t “ghost”!

While therapeutic situations differ, says Thomson, clients will average between 12 and 20 sessions, particularly with goal-oriented models like cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT).

“Let’s say I’m a client in therapy with generalized anxiety, and I’ve had 10 sessions. I’ve noticed a decrease because I’ve been working on some behaviour changes to help reduce it. At that point, the therapist can do a progress check on my initial goals and see how I’ve been doing with practising those skills — whether it’s behaviour changes, regulating emotions, or challenging an automatic negative thought to let it go and move on. Do I feel confident that I can maintain that without the therapist’s support?” For the therapist in this situation, says Thomson, rather than a complete termination, “maybe we switch the frequency of sessions. I typically see clients every two weeks. So why don’t we try seeing each other once a month for what we call maintenance-type therapy? If the skill implementation isn’t going so well, then we can go back to where we left off.”

At every stage of the process, the key to success is being comfortable communicating your feelings. You’re there to gain insight and develop the skills to grow, heal, and cope. Your therapist should be in your corner all the way.

If they do or say something truly unprofessional, and the organization they are registered with has a code of ethics and disciplinary measures, you can make a complaint. Check the laws and regulations in your province or territory to determine how to proceed in this kind of situation.

Resource: Fact Sheet: Common Mental Health Myths and Misconceptions.

Further reading: Weaving Through the Challenges: The ABCs of Finding an ACB Therapist

Moira Farr

An award-winning journalist, author, and instructor, with degrees from Ryerson and the University of Toronto. Her writing has appeared in The Walrus, Canadian Geographic, Chatelaine, The Globe and Mail and more, covering topics like the environment, mental health, and gender issues. When she’s not teaching or editing, Moira freelances as a writer, having also served as a faculty editor in the Literary Journalism Program at The Banff Centre for the Arts.

Related Articles

A friend of mine is struggling with her mental health. Something happened recently that sent her life into a tailspin, and she is having trouble coping. She can’t stop crying and is barely eating and sleeping. She has lived with depression for a long time, and it’s been manageable, but now she is at an all-time low. I’m worried about her. I’ve been talking to her about it, and I suggested she get some help from a therapist, but she isn’t ready. “I’ll just find a way to get through it on my own,” she says. Sound familiar?

I know firsthand that it can be tough to recognize when you need help. Years ago, when I was going through a major life crisis, it took me too long to ask for help. Later, I could see that I should have reached out to someone sooner. Why is it so hard to ask for help with our mental health? Would it surprise you to know that 60% of people with a mental health problem don’t seek help?

The power of stigma

That’s the power of stigma. I was worried about what people would think. The shame of admitting to myself that I was having a problem was so paralyzing that it kept me from getting help. I became filled with self-doubt. I started to lose trust in myself. Was I going to become one of ‘those people’? My imagination went wild with images of dismal institutions with bars on the windows and shock therapy.

The world influences our beliefs

Where did I get these ideas? We can call it cultural conditioning. We have been influenced to think of mental illness as frightening and debilitating and to see people who are dealing with mental health problems as unstable, violent, or dangerous. The media plays a big part in perpetuating the harmful stereotypes of mental illness. Mass media, television, and film have been shaping our ideas for a long time about what mental health and mental illness look like. The villains in the movies are so often characterizations of a person with a mental health condition. There are countless depictions of people with a diagnosis of schizophrenia portrayed as violent, unstable, and dangerous. These are not accurate or fair representations.

Just as media needs to be viewed with a critical eye, we should check our own assumptions about mental health and mental illness. We can inform ourselves about the facts, and we can learn how to be better allies to others.

5 Ways you can help

Everyone has a role to play in creating an inclusive community. Here are 5 ways you can help:

- Get the facts. Educate yourself about mental illness and share with family, friends, work colleagues, and classmates.

- Get to know people with personal experiences of mental illness so you learn to see them for the person they are rather than their illness.

- Be aware of your attitudes and behaviour. Choose your words carefully. Avoid stigmatizing people by seeing the person first and not labelling them by their mental illness.

- Challenge myths and stereotypes. You can help challenge stigma by speaking up when you hear people around you make negative or wrong comments about mental illness.

- Treat everyone with dignity and respect. Offer support and encouragement.

Where to find help

All those years ago, I wish help had been easier to find. Things have changed! If you or someone you care about might need some support, there are many options now. Here are some suggestions:

Wellness Together Canada (2020-2024)

To connect with a mental health professional one-on-one:

- call 1-888-668-6810 or text WELLNESS to 686868 for youth

- call 1-866-585-0445 or text WELLNESS to 741741 for adults

Kids Help Phone

Call 1-800-668-6868 (toll-free) or text CONNECT to 686868. Available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week to Canadians aged 5 to 29 who want confidential and anonymous care from trained responders.

Visit the Kids Help Phone website for online chat support or to access online resources for children and youth.

Mental Health Services across Canada

Find a Canadian Mental Health Association in your area

Hope for Wellness Help Line: 1-855-242-3310

Offers immediate mental health counselling and crisis intervention to all Indigenous peoples across Canada. Phone and chat counselling is available in English, French, Cree, Ojibway and Inuktitut.

Author: Nicole Chevrier

An avid writer and photographer. A first-time author, she recently published her first children’s book to help children who are experiencing bullying. When she isn’t at her desk, Nicole loves to spend her time doing yoga and meditation, ballroom dancing, hiking, and celebrating nature with photography. She is a collector of sunset moments.